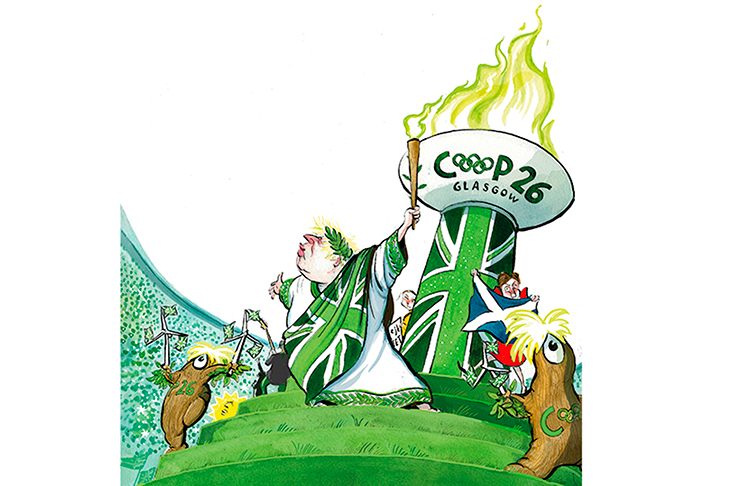

Zero possibility

Sir: Katy Balls is right to conclude that the government is ‘not being upfront’ on the bill for net zero and who will pay (‘The green games’, 17 April). As the Covid pandemic has revealed, expectations need managing, and without an urgent agreement on a consistent set of policy guidelines which embrace fairness, energy security and affordability, the whole net-zero project could backfire.

Whichever way you approach the problem, the costs of transitioning to net zero by 2050 are massive, with estimates ranging from £50 billion p.a. (Climate Change Committee) to £100 billion p.a. (National Grid), and the burden falling most heavily on those who cannot afford it. So while they receive little media airtime, it is no surprise that a growing number of people are challenging the activists’ and metro-liberal assumption that the UK (which accounts for less than 1 per cent of global carbon emissions) has a ‘moral responsibility’ to lead the world towards net zero.

The UK and a very hesitant EU are the only ones among the world’s 18 largest greenhouse gas emitters to have submitted detailed emission-reduction plans ahead of COP26. Now would be good time for the government to come clean and tell it how it is: namely that for very good reasons — such as technological constraints, security of supply, industrial competitiveness and affordability — reaching the net-zero target by 2050 might not be possible.

Boris will not want to be a COP26 party pooper — but industry and consumers would breathe a sigh of relief.

Clive Moffatt

London SW1

Rod’s wrong

Sir: As Shirley Williams’s son-in-law, I have no problem at all with Rod Liddle’s views on my mother-in-law’s political career — even if I did find him comparing Shirley to Pol Pot slightly excessive (‘How I’ll remember Shirley Williams’, 17 April). However, as the husband of her daughter, Rebecca, I feel I must correct the facts concerning my wife. Rod asserts that Shirley ‘moved house to ensure that her daughter, Rebecca, was able to attend a grant-aided school, Godolphin and Latymer, which she knew had absolutely no intention of becoming comprehensive and instead went private’, going on to make the case that this was hypocritical.

The facts are these. Rebecca started school at Godolphin in 1972 when Sir Edward Heath was Prime Minister and the selective system was very much in place. In 1977, by which time Rebecca’s mother had become education secretary, Godolphin held a ballot and decided to go independent. As Rebecca had already been at Godolphin for five years, Shirley told her that she could stay if she wanted — even though she knew she would pay a heavy political price if Rebecca did so. However, Rebecca decided to leave, instead transferring to the newly comprehensive Camden School for Girls. So Rebecca went to a comprehensive school at the first available opportunity, and the truth is the exact opposite of what Rod Liddle asserts. There have been left-wing politicians who have done what Rod Liddle says — but Shirley was not one of them.

Stephen Agar

Little Hadham, Ware

Shallow sympathy

Sir: Fiona Mountford describes accurately the inability of many in society to deal with the grief of others (‘Mourning sickness’, 17 April). I think that it is only when you have really felt grief that you understand it. The shallow emojis and expressions of easy sympathy that one sees on social media arise because we have successfully excluded death and dying from our conversation and our lives. Deep down, we are terrified of having to face it. Dying is what happens to old people in care homes, not to us. Let us hope that the sight of the Queen in her sorrow will make some face up to death and start to show real kindness to the grieving.

Mrs L. Hughes

Newton Abbot, Devon

Poor Miss Pym

Sir: On reading Philip Hensher’s review of Paula Byrne’s The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym (Books, 10 April), I was reminded of the sad occasion when I typed (at Jonathan Cape’s dictation) a letter to Miss Pym informing her that as her previous novel had not sold 3,000 copies — the breakthrough figure for profitability in those days — he would not be able to publish her future work. The truth was that Jonathan had exacting standards where his female authors were concerned, which poor Miss Pym, ‘that woman with a face like a horse who writes about vicars’, did not measure up to.

On the other hand, on the strength of a rather lukewarm report by the poet William Plomer on the manuscript of The Beautiful Visit, Jonathan said: ‘I think we’ll have a look at this one.’ When the glamorous figure of Elizabeth Jane Howard appeared in the office, her literary future was assured.

Caroline Brooks

Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire

A long line of rubber

Sir: I was surprised to read in the Spectator’s Notes that germinated rubber seeds shipped from Kew to Ceylon ‘failed’ (10 April). They did not fail but thrived, as do their descendants to this day.

Royston Ellis

Induruwa, Sri Lanka

Indian-English

Sir: Charles Moore might like to know that there is an updated version of the Anglo-Indian glossary Hobson-Jobson (Notes, 17 April). Nigel Hankin’s Hanklyn-Janklyn was published in 2003 by India Research Press, New Delhi. I was lucky enough to get my copy from the author after a fascinating day spent with him in Old Delhi.

Emma Corke

By email

Write to us letters@spectator.co.uk

Comments