We were in a detention centre for migrants in Tripoli and we came to a big locked door. It was impressively bolted and padlocked. Someone murmured that we didn’t have time to look inside. But I felt somehow obliged to do so.

Outside in the sun I had already said hello to about 100 migrants — almost all of them from West Africa: Guinea-Conakry and Nigeria. They were sitting on the concrete in rows, their heads in their hands; the men in one group, and about half a dozen women a little way off. They had been here for months, in some cases, and they wanted to go home.

Kwasi Kwarteng and Kim Sengupta consider the future of Libya:

‘J’ai faim,’ said one of the men. ‘C’est pas bon ici,’ said another. When I said that I was the British Foreign Secretary they cheered and clapped, because it is UK cash that is helping them to find a way out. It is (at least partly) thanks to UK taxpayers that this group were about to be put on buses and taken to the airport.

As they told me, they had first intended to go to western Europe. Their plan had been to get to ‘France, Allemagne, Grande-Bretagne’. They had paid people smugglers €1,500 each — a huge sum, more than their annual wage. Then they had been intercepted, detained — or rescued, depending on your point of view — and sent here.

It was thanks to UK investment that this centre seemed at least vaguely hygienic, in spite of the press of humanity. We had been shown the new latrines, and even though they were not yet finished, you could sense that an effort was being made. But now we had come to a series of locked doors, and I felt I had to understand the scale of the problem. ‘Just look, don’t go in,’ I was advised. The bolts clanked open.

It was like a scene from some hellish Victorian etching about prison life. In the first set of rooms were the criminals, men — they were all young sub-Saharan Africans — who had been picked up by the Libyan authorities (an array of militias), arrested for dealing in drugs and other misdemeanours.

The next room was vast — the size of a football field — and contained about 500 souls, lying serried on towels or mats. I started again to talk to them, in French, but some sort of commotion began. People began drifting towards us. Our minders suggested it was time to move on. I had wanted to see behind that locked door — and the true scale of the problem this centre is dealing with — because once again the numbers are starting to swell.

The migration season is upon us. The winds are calm, and on the level sea the loathsome flesh traffickers are intensifying their trade. Already about 1,000 migrants a week are making landfall in Italy, with an unknown number perishing in the sea, in the desert and in centres like the one I saw.

Every week they will be pressing on up the European road network to wherever will have them. On the plane to Tripoli, the UN special representative, Martin Kobler, showed me a breathtaking demographic map — the root of the problem.

Twenty years ago we were so naive as to think that global population growth was slowing. Not any more — certainly not in Africa. Immediately to Libya’s south is Niger, where the population is predicted to treble in the next three decades, from 20 million to 72 million. To the east of Niger — and sharing another vast border with Libya — is Chad, set to leap from 14 million to 35 million. To the south-east, Sudan is heading for 80 million, Egypt for 152 million, Ethiopia to 189 million.

Add in the vast human production line of West Africa — where Nigeria alone is set to hit 400 million — and you can see why these detainees are just the harbingers of what will be one of the great challenges of our lives. The population of Africa already stands at 1.2 billion, but is growing so fast that it is impossible to see how the continent can provide enough jobs for its people.

No wonder that they look north, to the immense prosperity of our elderly European continent — where the population is actually falling (it is predicted to decline from 740 million to 707 million by 2050). On a basic Archimedean principle of displacement, the tide is rolling from south to north.

Of course we must not deprecate these people — their ambition and bravery in seeking a new life. Across much of stubbornly unreproductive Europe a certain amount of immigration is going to be welcome. But the pace and scale of what is happening is surely unsustainable.

If it carries on like this, we will see renewed social strains in Europe, and dire political consequences. We have to help them stay in their own countries, to find jobs, and we must help African economies to move up the value chain. (It is staggering, 40 years after I first came to sub-Saharan Africa, to find there is still virtually no real manufacturing industry outside South Africa.)

We have to deal with the economic roots of the migration crisis. But we must also recognise that there is a particular problem on the southern shores of the Mediterranean, a political crisis that has given the racketeers their opening.

That crisis is Libya. That is the gaping exit from which the migrants are making their journeys, and unless we staunch the wound the haemorrhage of humanity will continue.

To look at Libya, the place is physically a mess — half-finished buildings, burned-out cars, and the entire landscape plagued with plastic litter, wind-ripped black bags that flutter like birds on every fence.

The political mess is far worse. For 42 years the Libyans were under the rule of Gaddafi. That rule was vile, incompetent, tyrannical, ludicrous — but it kept the country together. Today there is no single pole of authority — and there has not been since Gaddafi was removed from office in 2011, before being dragged from a storm drain and murdered in repulsive circumstances.

Libya is fantastically rich in oil — but that wealth is not being used for the benefit of the Libyans. How could it be? For the past six years a civil war has sputtered between east and west. Prime Minister Serraj — the man whose authority is recognised by the international community — is doing his best, but in reality he struggles to exert power beyond Tripoli.

The country is contested between a patchwork of militias — some of them more Islamic-extremist than others — and the Libyan National Army, commanded by General Haftar. To some extent it is a battle for oil, and money. But it is also factional, regional and tribal. It was 15 months ago that the parties came together at Skhirat in Morocco, and agreed a new political framework.

Since then there has been deadlock, with one set of politicians refusing to recognise the other. There is little that resembles a Libyan state — certainly no body that can claim the monopoly on the legitimate use of violence — and in this vacuum the gangsters and people smugglers can do their business.

I had lunch in Tripoli, in a lovely restaurant in the heart of the ancient Roman city, looking out at the arch of Marcus Aurelius that used to dominate the cardo, or main shopping street. I asked a Libyan politician the question that we are bound to ask — all those of us who come from countries that were involved in the removal of Gaddafi.

Suppose the security situation allowed us to do vox pops; suppose we went out into the streets and asked about the changes since 2011, and the ‘Arab Spring’. What would they say? ‘I am afraid that many people would say they were better off under Gaddafi,’ he said.

Now Gaddafi was a monster, a man whose state engaged in torture and repression of all kinds. No one could conceivably want him back. It is a measure of the depths of the present anarchy that his reign could enjoy any kind of favourable comparison.

There has to be a better option for Libya; and so it is very good to report that — at last — we are seeing the glimmerings of hope. In the last few days there have been important meetings: between Prime Minister Serraj and General Haftar.

The east and the west of the country show signs of coming together: Agileh Saleh, veteran president of the Tobruk-based House of Representatives, has travelled to Rome to meet Abdurrahman Swehli, president of the High State Council based in Tripoli. Thanks in particular to the diplomacy of the Egyptians and the UAE, a consensus is starting to emerge not just between the Libyan politicians, but also — crucially — between the outside powers with an interest in Libya.

At the heart of that consensus is an understanding that the Skhirat agreement can be improved so that it wins greater support across Libya, and a way must be found of maintaining overall civilian control of the military while also recognising the role and importance of General Haftar. There is a feeling of momentum, and a widespread sense that now is the time for the UN to help Libyans to grip this political process.

This is the moment for the key players in Libyan politics — and they can be counted on two hands — to come together in a mature and generous spirit, and create a new settlement for their country. The signs are that they are capable of doing it.

The UK is actively involved in supporting that effort, not just because of our role in 2011, but because Libya is crucial to our future. In its current lawless state this vast country is a potential catapult or trebuchet, capable of discharging huge numbers of people across the Mediterranean.

If Libya continues in its current condition we risk having a failed state — a haven for terrorists, gun runners and people traffickers — only a few miles from the EU’s southern shores. But if Libya’s leaders seize this moment, the opportunity is immense.

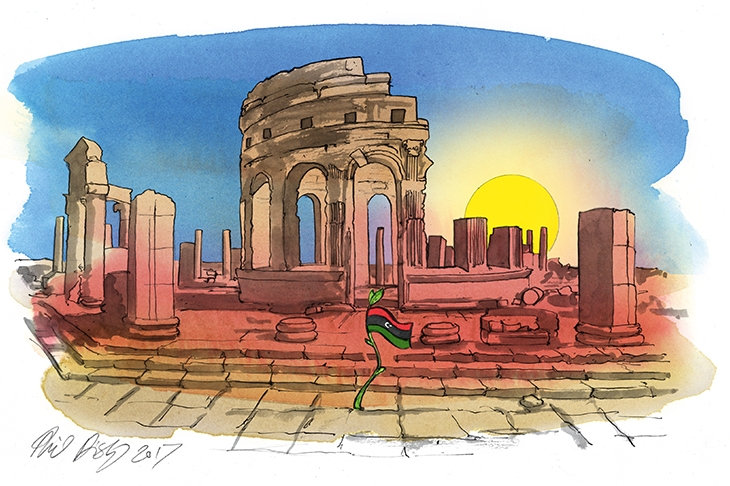

If they can put aside their differences, and stabilise the country, then this place of six million will not only be able to make sensible use of their amazing patrimony of hydrocarbons. They can open up some of the greatest tourist sites in the world, including Leptis Magna — currently too dangerous to visit.

On the streets of Tripoli you can see people beginning to relax, drinking coffee and fizzy drinks outside the cafés. It is now six weeks since a tank round went into one of the big hotels, and spirits are rising. If you shut one eye to the capsized warship in the harbour — sunk by the RAF in 2011 — you can see how it might be a fine resort town.

The beaches are bone-white sand; astonishing. The hotels are waiting to be filled. The sea is turquoise and lovely and teeming with fresh fish. Libya was once the birthplace of emperors, a bustling centre of the Mediterranean world. It can have a great future. All it takes is political will, and the courage to compromise.

Comments