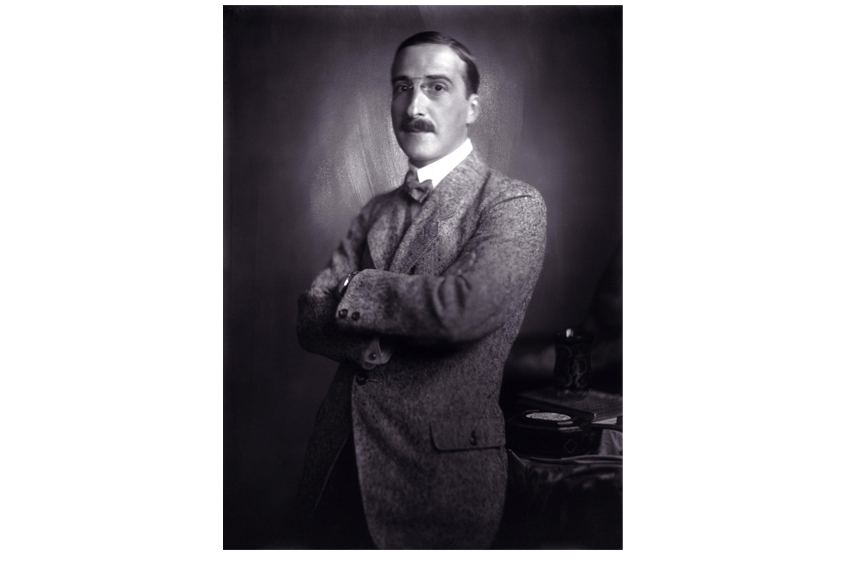

In February 2009, in a review in these pages of Stefan Zweig’s unfinished novel, The Post Office Girl, I wrote: ‘Here surely is what Joseph Conrad meant when he wrote that above all he wanted his readers “to see.’’ In The Post Office Girl Zweig explores the details of everyday life in language that pierces both brain and heart.’

Especially the details of loneliness, I should have added. Intimations of suicide darken this novel, and in 1942, with the manuscript incomplete, Zweig, age 60, and his much younger second wife, Lotte, poisoned themselves in a small Brazilian town and died in bed with her embracing him.

It is telling that she did the embracing. Zweig, we learn from this biography, was a self-confessed loner, quite cold in person while passionate about certain kinds of things he collected all his life: rare manuscripts — he had a Handel score; objects, such as Beethoven’s desk and violin; and drawings — he had two by Rembrandt.

Who reads Zweig now? Of course anyone literate should read his only two novels, Beware of Pity and the unfinished The Post Office Girl. But from at least 1904 until his suicide, Zweig became an increasingly celebrated author, stupendously famous even in Latin America, who filled Carnegie Hall with 2,800 listeners, and spoke at Freud’s funeral.

Most of his oeuvre consisted of biographies of famous past and living men, plays, essays on literature, and the avalanche of letters he wrote from his late childhood until his death. He knew writers like Schnitzler, Hesse, and Thomas Mann, and once watched Rodin at work, a rare example of the biographer telling us what something was really like. Periodically he kept a diary. Even just before his final fatal moment he wrote letters to friends and acquaintances and to his first wife, Friderike. He explained that after years of considering it, he had decided to end his life. It is a mark of his depression that he could write to Friderike: ‘When you get this letter I shall feel much better than before.’

Since Oliver Matuschek says next to nothing about the content of what Zweig wrote, barely touches on only one of the two novels, and does not describe what he said in his many lectures, it is impossible to know what made Zweig so famous. Indeed, had I not read The Post Office Girl I would have laid this book aside after the first 100 pages.

On the whole what we have here are arid reports. Zweig goes to see Einstein, who was a great fan; what happened? He becomes friendly with Freud, even writes a short biography of him and pays the great man a visit with Salvatore Dali in tow — who paints Freud.

That must have been a long visit: what happened? These two events, which any sentient being would like to hear about, are given no more weight in this biography than the exact location of one of Zweig’s hotels in Manhattan, and less attention than the second Mrs Zweig teaching her Brazilian servant how to cook Zweig’s favourite Palatschinken, Schmarren, and Erdapfelnudeln.

This is not to say that Zweig is not intrinsically interesting. Born into a well-off Viennese family of assimilated Jews, he was anti-Zionist:

I see it as the mission of the Jews in the political sphere to uproot nationalism in every country, in order to bring about an attachment that is purely spiritual and intellectual. Having sown our blood and our ideas throughout the world for 2,000 years we cannot go back to being a little nation in a corner of the Arab world. Our spirit is cosmopolitan — that’s how we became what we are, and if we have to suffer for it, then so be it. So I think it’s no coincidence that I am internationalist and a pacifist — I would have to deny myself and my blood if I were anything else.

I declare a sympathetic interest.

Although he spoke to Jewish groups, his audience throughout Europe and the rest of the world was much vaster than a Jewish one. But he knew what Hitler and Hitlerism meant, and fled to England, then the US, and finally, as a last resort, Brazil; but for his last 20 years Zweig always thought of ‘the little phial’, that is suicide, menacingly hinted at in the The Post Office Girl.

He wrote about women, sometimes erotically, but although he fascinated them, and had ‘episodes’ both before and after his first marriage, he ‘gave the impression of being inhibited and unsure of himself in the company of women’, preferring to talk about sex with his men friends.

One of the weirdest signs of this was his wedding invitation: ‘I should like to request your attendance tomorrow … at the homosexual ceremony.’ His bride-to-be, who had pursued Zweig for some years, was only recently divorced and because of that painful memory she asked ‘their friend Felix Braun to represent her instead’. Only men were present at the registry office, and when the registrar ‘expressed the hope that the happy couple would be blessed with many children … the groom, flanked by the bride’s male representative, burst into laughter.’ When he wrote — Zweig often preferred letters to contact — to his wife saying he would see her in a few days, she replied, ‘So how did you spend your wedding night, my dear?’

Oliver Matuschek recycles some admittedly dodgy rumours that Zweig may have been a flasher, but like most gossip-mongers retreats from the allegations. But Zweig himself recorded in an early diary entry that one evening he had ‘one of those unnatural episodes of the strangest sort, an encounter with the two brothers P, all very hasty but it did the trick’. Thomas Mann, who admired Zweig, wrote after his suicide, ‘I suspect that sex had reared its ugly head again, and that he feared some sort of scandal. He was vulnerable in that regard.’

Well, maybe. But Zweig was a depressive his whole life, fearful of fame, maybe of women, of getting old, of whether his passion for the manuscripts of the famous was unworthy. If you want information about Stefan Zweig there is plenty in this biography. But what he left behind that is lasting — barely mentioned here — are Beware of Pity and The Post Office Girl. What a legacy.

Comments