‘I detest lateness,’ texts Tristan Tate, who’s offered to pick me up from a hotel in Bucharest. ‘So I’ll either be 15 minutes early or right on time.’ Minutes later, he messages again: ‘All my talk on being late and cops pull me over haha.’

Tristan and his older brother Andrew seem to have a knack for getting into trouble. They’ve been accused of all sorts: rape, actual bodily harm, sex trafficking, controlling prostitution for gain, organised crime, money-laundering, witness-tampering. To the BBC and bourgeois parents everywhere, they are infamous: the vilest beasts of the manosphere, monetisers of misogyny and leading purveyors of far-right hate.

Are the Tates really that bad, though? They still face a number of criminal charges, their homes have been repeatedly raided and they’ve spent time in jail, but they deny all wrongdoing and have not yet been found guilty of anything. The big Romanian case against them appears to have stalled, after a judge ruled that the evidence wasn’t strong enough to go to trial, and the brothers have launched a suit in America against a woman they claim conspired to defame them through a fraudulent conspiracy. The Tates are confident that their complaint will be upheld and then all other charges will melt away. Perhaps I am gullible, or toxically male, but I can’t help believing them.

Tristan pulls up – only ten minutes late – in an Aston Martin. The police stopped him, he explains, because they couldn’t see his licence plate. ‘But they were friendly. They know me.’

He drives us to one of his favourite restaurants. ‘If you don’t mind, I’ll sit here,’ he says, plonking himself down at the table. ‘I don’t like having my back to the room. A crazy Ukrainian guy came and tried to stab an employee of my house a few days ago.’

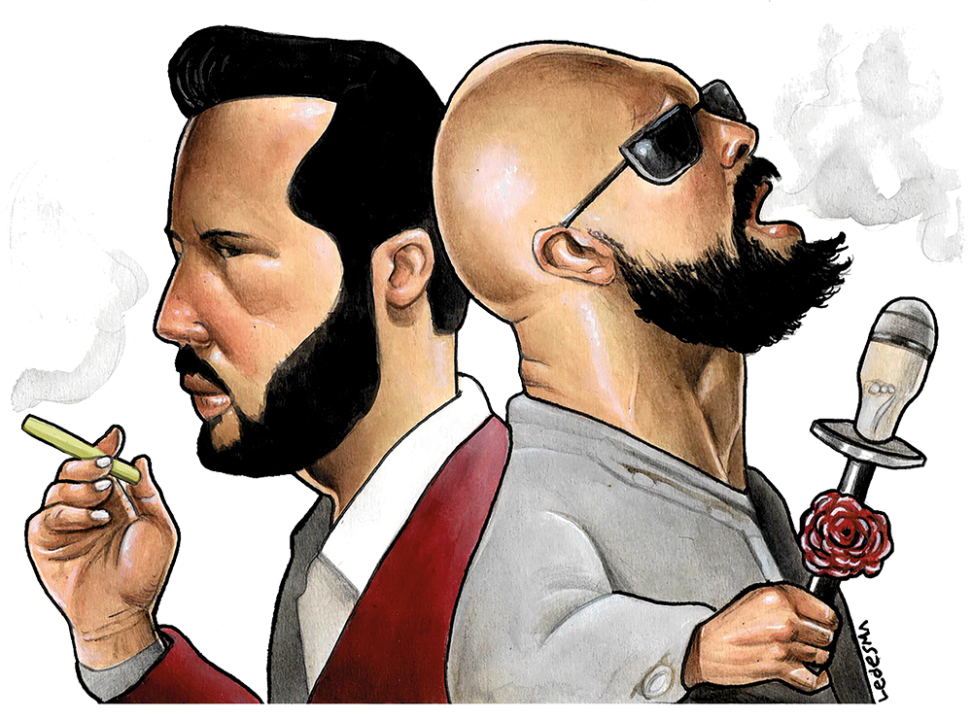

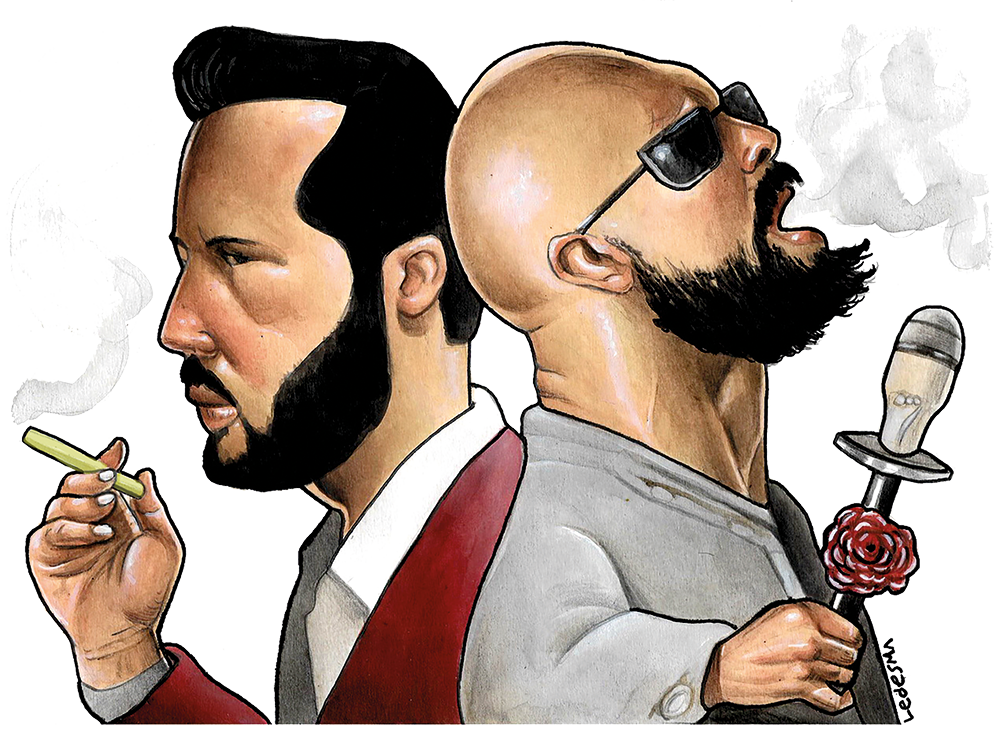

Tristan is the gentler Tate. He cultivates a more civilised air. He smokes gold-tipped Sobranies and wears a brown three-piece suit with a Union Jack pin on the lapel. He has good manners, speaks to the locals in Romanian and doles out generous tips. ‘To you I sound fluent, to them I sound like Borat… but everyone here knows that we were set up because this happens to wealthy Romanians all the time: a fake case, they take all your money, later they find out it’s not real.’

He orders us sushi with foie gras and a vast amount of steak. As we start to eat, two young men approach. ‘I’m like a crazy fan of you,’ says one, a Brazilian, before asking for a selfie. Later, as Tristan asks for the bill, another male superfan approaches wanting a photograph. ‘I promise I didn’t pay these people,’ he says. ‘I have a prolific number of female stalkers as well.’

Dinner is meant to be a prelude to a longer interview with Andrew tomorrow. Tristan drops me off and says he’ll send a car in the morning. Overnight, we learn that Charlie Kirk, the MAGA star, has been killed at a university in Utah.

‘A crazy Ukrainian guy came and tried to stab an employee of my house a few days ago’

The Tates didn’t know Charlie, but they had friends in common – the commentator Candace Owens, for one – and shared some views about the plight of young men in this hyper-liberal age. Kirk’s death seems to disturb them profoundly. When I turn up the following morning, Tristan tells me he hasn’t slept. ‘The media’s responsible for this,’ he says. ‘Charlie was a good guy who loved his family and his nation. I saw the video of him getting shot and I thought that could be my brother.’

He gives me a quick tour of their famous residence. It’s like being in a 15-year-old’s Ferris Bueller-esque fantasy. Tristan shows me the expensive cars and gadget-stuffed rooms. There’s a personal trainer and a couple of chirpy tech-guys with laptops pumping out content. Then I’m ushered into a smoking room. It has high-backed leather chairs. A young mixed-race woman, introduced as Andrew’s girlfriend, brings coffee and then disappears. ‘She’s another of our alleged victims,’ says Tristan.

Suddenly Andrew, the so-called ‘Top G’, appears as if from nowhere. In one motion, he slips a gold watch on to his wrist and shakes my hand. Kirk’s assassination looks like a professional job, he tells me, skipping the small talk. ‘We live in a battle for influence,’ he says. ‘So if you’re someone like Charlie Kirk or myself with massive influence, you’re a problem. And the people who disagree with you want you to go away.’

The Tate brothers were born in 1986 and 1988, 19 months apart, in Washington, DC. Their father, Emory, was an African-American air force sergeant and an international chess master. He met their mother, a British dinner lady called Eileen, while stationed at an RAF base in Bedfordshire.

‘I’m seen as a national security issue because of how many young men obey me’

Andrew and Tristan moved to England with Eileen after their parents divorced in 1997. They lived on a council estate in Luton, near Tommy Robinson, and the brothers dropped out of school at 16 in order to make money. Andrew worked for a fishmonger; Tristan at a Pret A Manger in Luton airport. They discovered kickboxing. Andrew won a world championship belt; Tristan a European one.

Their early adulthood coincided with the rise of the internet. Andrew spent large amounts of time on MSN Messenger and discovered his unique talent for saying truly shocking things on camera. He posted videos called ‘Offending what’s Trending’, which later came to be called ‘Tate speech’. The young brothers were drawn into terrestrial television, too: they set up a TV advertising agency. In 2011, Tristan appeared as a guest on the reality show Shipwrecked; five years later, Andrew made it on to Big Brother.

Around that time, a video was posted online of him beating a woman with a belt. Andrew and the woman on the receiving end have long insisted that the lashing was consensual. Soon after, the two brothers moved to Bucharest. Reports suggest Andrew was running away from allegations of sexual assault; Tristan says they found work commentating in English on Romanian extreme fighting events. Bucharest at the time was host to a budding online sex industry and the boys soon set up a small ‘cam girl’ studio. ‘I thought: I’m in Romania,’ recalls Tristan. ‘Do as the Romanians do.’ But the seediness of that enterprise has dogged them ever since.

Their real business bonanza came not from sex but from online education – or rather Hustlers University, which then became The Real World, an online platform for young men looking for purpose and ways to make money outside traditional employment. In 2023, for several million dollars, the brothers bought the domain name university.com, ‘to make a statement’, they say. They could afford it: The Real World was generating somewhere between $60 and $120 million a year by charging monthly fees, starting at $49, for teaching students how to make fast money from e-commerce, cryptocurrency and artificial intelligence.

That’s what Andrew wants to talk to me about. Sitting across a mahogany table, puffing on his large shisha, he explains how his students learn how to build AI-customer service tools and rent them out to small businesses or build AI chatbots for lonely people online.

But he keeps digressing into dark ruminations about the nature of the world and how he might end up like Charlie Kirk. ‘I’m seen as a national security issue because of how many young men obey me, and I’m seen as a problem, which is why they weaponise their entire mainstream media into convincing [people] I’m a bad person.’ He rails against the elites, the decline in living standards in England, the pitfalls of sexual equality and ‘financialised capitalism, which is leading into monopolised capitalism, because everyone’s just putting their money into the last few producers of product’. There’s a money counter in the corner of the room.

Who are the elite? ‘It’s very rich people who want to stay rich,’ he says. ‘They don’t live among the mess they create.’ A secret cabal, then? ‘That’s actually quite a cartoonish thought,’ he replies. ‘I’m sure there’s lots of different cabals and I’m sure there’s lots of crossover between them.’

The Tate brothers are convinced that they and their businesses are targets of a concerted government campaign. ‘I’ve gone from a Luton council estate to the upper echelons of fame and power and money,’ says Andrew. ‘And I am telling you that I am the target of a military intelligence operation to dampen my influence and destroy my school.’

He and his brother offer overlapping theories as to why the deep state wants them stopped. It’s because of their views on immigration, their criticisms of Ukraine, their opposition to Covid lockdowns and vaccine mandates. It’s because the system wants to crush young men and he inspires them. Andrew says his online academies represent a threat to the scam that is higher education. ‘Big education is as powerful as Big Pharma,’ he says. His online school has been the subject of relentless cyber attacks, he says, ‘but like a cockroach, I refuse to die’.

Andrew and Tristan also suggest, darkly, that their real legal problems began in 2022 soon after they turned down $50 million from a large PR group, whose lawyers wanted them to agree to stop spouting certain opinions. But they also now refuse to name the organisation. ‘Call me paranoid if you like,’ says Andrew.

‘All these demons, I’ve grabbed them by the neck and I’ve forced them to join my legion’

Trying to make Andrew reveal himself is like banging your head against a wall. You hope something cracks but you end up dizzy. He calls me ‘sir’, over and over, and refuses to show weakness. ‘Absolutely not,’ he says when asked if his parents’ divorce made him sad. ‘Zero per cent,’ he says when I ask if he’s ever lonely. ‘Psychology is pretty shit, by the way.’

He admits that he doesn’t sleep and that he has ‘to a degree, if it is real, which I don’t believe it is, some kind of anxiety disorder, I can’t sit still, I can’t relax… but all these demons, anxiety, panic attacks, all these things, I’ve grabbed them by the neck and I’ve forced them to join my legion’.

The Tates live in their own world, which may or may not be real. Andrew is obsessed with ‘the Matrix’, a concept invented in the 1999 sci-fi film about machines enslaving man. It’s also the metaphor he uses to persuade young men to join his school in order to free themselves from the clutches of the system. Yet he also seems really to believe that we exist in some cruel virtual game.

‘I’ve always had a splinter in my mind that is permanently bothering me,’ he says. ‘Do you ever feel like you’re living in a simulation?’ In that moment, I do.

Comments