I’m currently in Cornwall with my family and whenever I spend a lot of time with my children I’m constantly reminded of the opening lines of ‘This Be the Verse’: ‘They fuck you up, your mum and dad. / They may not mean to, but they do. / They fill you with the faults they had / And add some extra, just for you.’

One of the faults my late father passed on to me was an obsession with sports cars. As he cruised along the motorway in his Austin Maxi at a steady 70mph he would point out every fast car that passed us, usually accompanied by a barrage of facts: ‘Ooh look. That’s a Lotus Esprit. I think that’s an S1 — yes, it’s an S1. It has the same four-cylinder engine that was used in the Jensen Healey.’

This lifelong interest of his wasn’t a complete affectation. As a teenage boy at Dartington Hall School, he’d developed a man crush on the racing driver and second world war fighter ace Whitney Straight, the son of the school’s co-founder Dorothy Elmhirst. Straight had gone up to Cambridge by the time my father arrived and already competed in his first grand prix. My father vividly recalled a thrilling ride from Dartington to London in Straight’s Brooklands Riley in which they averaged 90mph.

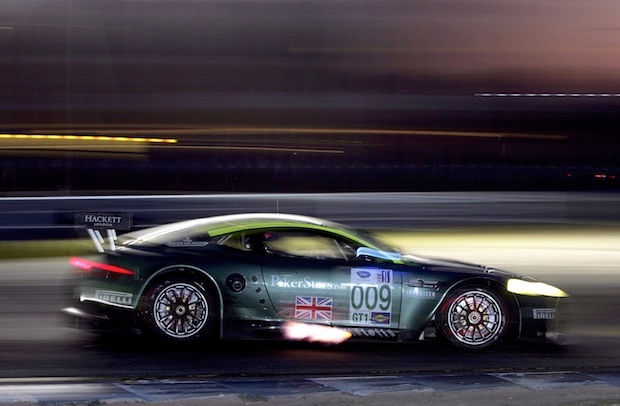

This exposure to motor racing at an impressionable age left my father with a yearning to own an expensive sports car. Throughout my childhood, he was always on the point of buying one and we spent many a happy hour poring over motoring magazines and discussing the comparative merits of different classic cars. It was taken for granted that the vehicle in question would be British, but should it be an Aston Martin DB5 or an E-Type Jag? It wasn’t until I was relatively old — well into my twenties — that I realised he was never going to act on this impulse.

My three sons are now aged five, six and eight and, like most little boys, they’re fascinated by fast cars. For the past year or so, I’ve been cultivating this interest and, without quite realising it, repeating the conversations my father used to have with me. As I putter along the motorway in my VW Transporter, I find myself pointing out the sports cars overtaking us, adding little factoids I’ve gleaned from What Car? magazine: ‘Ooh look. That’s a Porsche Cayman. It shares the same platform as the Boxster, but I prefer its sportier look. What do you think?’

Naturally, they all want to know when I’m going to buy one of these exciting vehicles and I’m reluctant to tell them the truth, which is that, like my dad, I never will. Instead I explain that as a father of four, it wouldn’t be practical to own a sports car at present. Perhaps when they’re a bit older and less dependent on mummy and daddy to ferry them about…

Until I heard myself trotting out this excuse, it hadn’t occurred to me that my father used to pretend that he was in the market for a sports car for the same reason. Like me, he wanted his children to believe that this fantasy was firmly within his grasp. He was too embarrassed to admit that his own middle-classness — a middle-classness rooted in the self-denying puritanism of his nonconformist ancestors — ruled out anything as flashy as a sports car. What he’d really admired about Whitney Straight was his lack of inhibition. He was free in a way my father never would be.

Thinking about it, even this apparently self-deprecating account is too generous to my father and me. I’m implying a degree of self-awareness that, in truth, he lacked and I probably do too. He wasn’t just maintaining this charade for my benefit. At some level, he actually believed he was about to trade in his Austin Maxi for a Jensen Interceptor. To acknowledge that he’d never own a glamorous car would have been too painful, and convincing me he was on the verge of buying one was a way of convincing himself.

I daresay I’m guilty of the same self-deception when I tell my sons I might get a sports car when they’re a bit older. That’s the trouble with becoming a father. Your children inadvertently highlight your failures as a man and rather than confront them, you come up with an avoidance strategy that has the unintended effect of condemning them to repeat the same mistakes. At bottom, my father taught me not to act on my fantasies, to always err on the side of caution. And I fear I’m teaching my sons the same lesson.

Comments