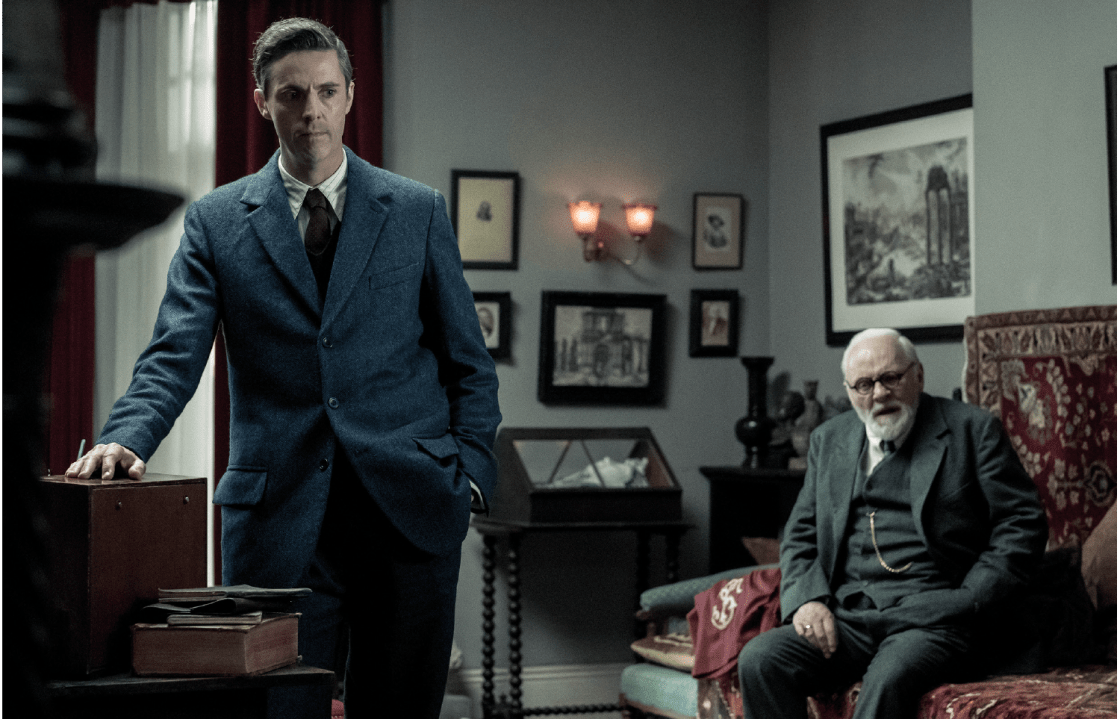

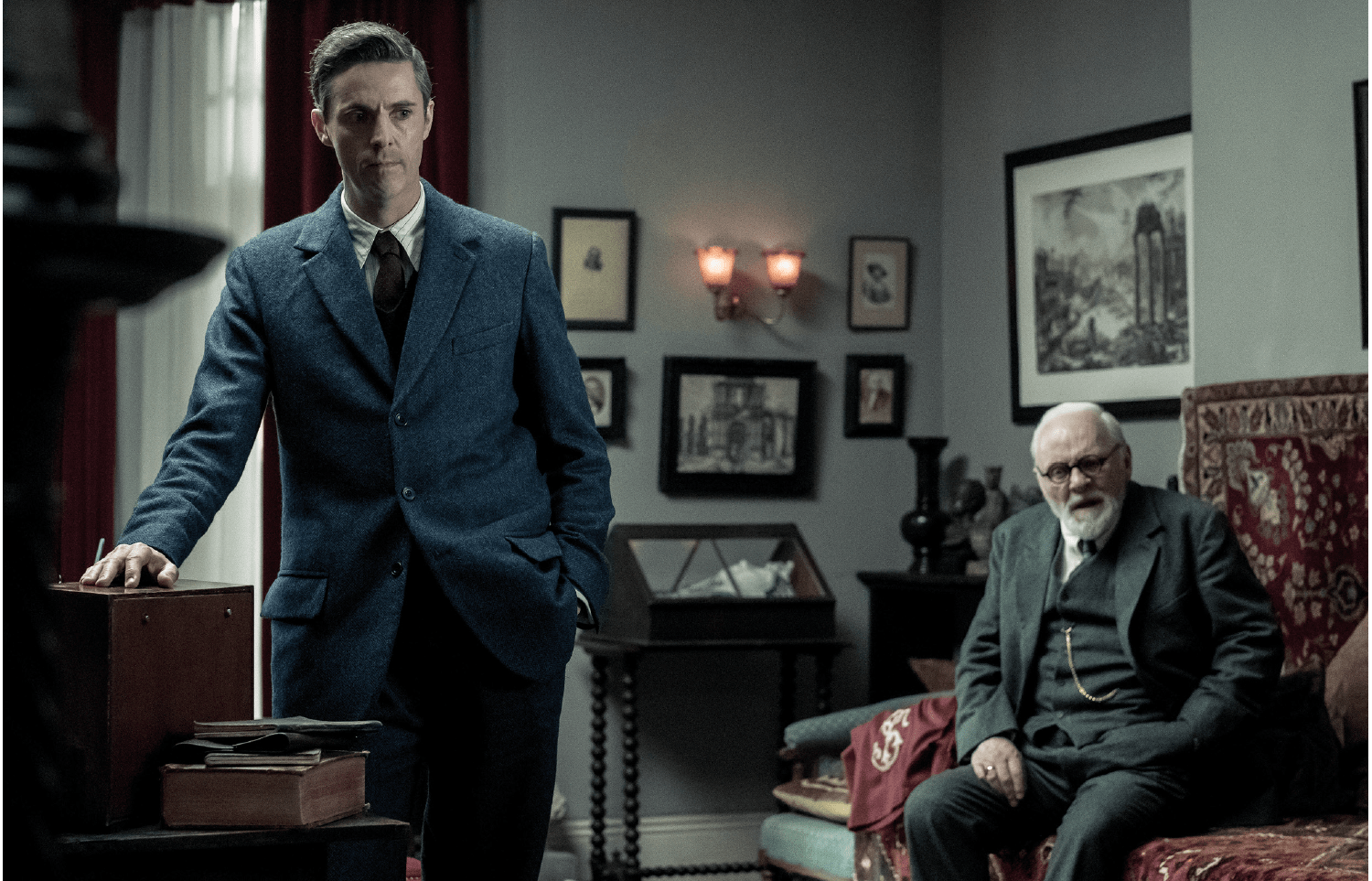

Freud’s Last Session stars Anthony Hopkins and Matthew Goode and is a work of speculative fiction asking what would have happened if Sigmund Freud and C.S. Lewis had met to debate the existence of God. What if two of the greatest minds of the 20th century had the chance to thrash it out? Thrash it out they do but, alas, they cannot thrash any life into this film. If you are planning to see it at the cinema, a few espressos beforehand may not go amiss.

It is directed by Matthew Brown, who co-wrote the script with Mark St Germain, on whose play it is based. It takes place on 3 September 1939, the day Chamberlain declared war after Hitler invaded Poland. Freud, an atheist, has invited Lewis, a man of deep Christian faith, to his Hampstead home. He has issued this invitation, he says, ‘because I want to know why a man of your supreme intellect could abandon truth and embrace an insidious lie’. Freud has jaw cancer, which is making his life intolerable. He’s in horrific pain and, given the film’s title, we know he won’t last for long. Is he seeking some last-minute reason to believe in God to offset his own terrors? And is this all happening because Europe is on the brink of conflict? The film doesn’t drill down sufficiently into its own conceit to tell us anything about that.

One has to admire a film that is solely interested in the mind. There’s not a high-speed car chase in sight

To counter the usual inertness of a two-hander, Freud is kept on the move, going from this room to that, out into the garden and back inside again. I kept wanting to shout at the screen: ‘For pity’s sake, let the poor old fella have a sit! Can’t you see he’s on his last legs?’ That’s about as roused, or as emotionally invested, as I ever got.

Lewis is first greeted by Jofi, Freud’s dog (a Chow Chow), who only appears once more in the film. This is a shame, as a Chow Chow always cheers everyone up. Freud’s house, which he shares with his daughter, Anna (Liv Lisa Fries), is dark, always dark, and could do with some cheeriness.

This film is not a flattering portrait of Freud. Here, he is angry, self-righteous, mocking, sarcastic, always on the look-out for any weakness Lewis might display. Lewis circles Freud politely and matters are always kept cordial – perhaps too cordial. Their discussions, although elegantly worded, don’t ever amount to much more than a classroom debate – if there is a God why is there pain? (etc., etc.) – and nothing ever really goes anywhere. For example, when it’s revealed that Lewis had nurtured a relationship with an older woman he tells Freud: ‘I won’t discuss this matter with you. My private life is precisely that.’ So that’s immediately closed down. On another occasion, Anna is revealed to have spent years in psychoanalysis for ‘the treatment of her complex’ but the ‘complex’ is never specified. Her analyst, by the way, was her father. At one point we see her explicitly relating a sexy dream to… her dad. Weird.

The film does try to escape its theatrical roots by including flashbacks and scenes outside of the Hampstead house, but these feel like distractions. The best reason to go and see it is Hopkins, who is as powerfully compelling as ever – even though he can probably do these roles in his sleep now. (The likes of Michael Caine, Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart must be furious: they never get a look in.) Although the argument at the film’s heart seems rather pointless – Lewis is no more likely to renounce his faith than Freud is to convert – one has to, ultimately, admire a film that is solely interested in the mind. There’s not a high-speed car chase in sight. Still, a few espressos would be good.

Comments