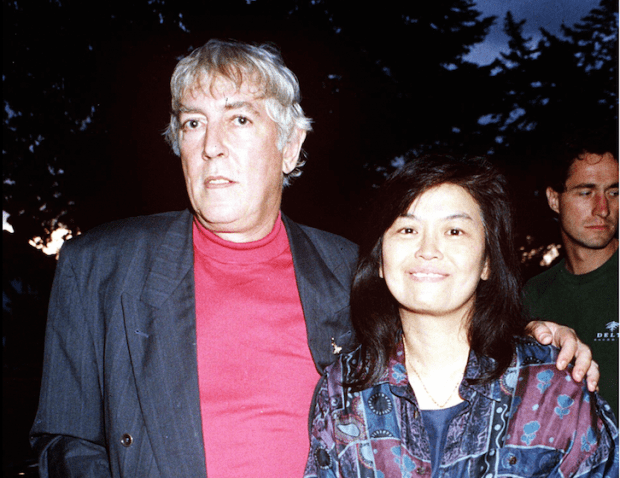

Amid the flurry of famous deaths during 2016, one particular passing has been more or less forgotten. Peter Cook’s third and final wife, Lin Cook, died on the eve of Advent, at the age of 71, shortly after the BBC broadcast Victor Lewis-Smith’s new documentary about Peter, for which Lin gave a rare interview. I got to know Lin in the Noughties, while compiling two biographical collections of her late husband’s work. It was an intriguing insight into the world of that strange showbiz phenomenon, the celebrity widow. Celebrity widows are a paradox – ostensibly public people, they’re actually intensely private. Lin personified this odd breed. Although I was in touch with her for over 15 years, when she died I realised I barely knew her at all.

I first met Lin in 2000, when I was invited to her home in Perrins Walk, a cobbled mews off Hampstead High Street where Peter had lived until his death, in 1995, aged 58. I’d heard a lot about this Queen Anne coach house, which Peter had bought in 1973, at the height of his success. This was the setting for the lost years that followed the collapse of his partnership with Dudley Moore, and the breakdown of his second marriage, to Judy Huxtable. If you believed what the papers said, until Peter met Lin this house had been spectacularly untidy, if not downright seedy. Yet whatever happened here in the past, Lin had since made it spick and span.

When I arrived at Perrins Walk, I realised this was an audition. Lin wanted to publish an anthology of Peter’s work, and she wanted to see if I was the right man to edit it. I’d never met Peter Cook, and my two previous books had both been about so-called ‘alternative comedians’, many of whom weren’t even born when Peter was in his prime. I was a fan but not an aficionado, so I was a bit surprised when she gave me the go-ahead. I’ve always suspected it was my surname which swung it, even though we weren’t related.

It was a tricky working relationship – how could it have been anything else? Lin could be very kind, bringing round toys for my small children (originally bought for her disabled daughter) but we were never going to see eye to eye about the task in hand. Lin wanted to tell the world about the caring, gentle man she knew. The world wanted to hear about his rock and roll excesses. Her deep, abiding love for Peter was an important part of his life story, but it was only part of the story. Many other people, who’d known him long before he met Lin, were far franker about his failings, even though they also loved him deeply. My potted biography became a balancing act, between Lin’s private impression of Peter and his public persona. For her, the word alcoholic was an unkind slur. For me, it mitigated his bad behaviour. Ironically, her refusal to countenance this term, motivated entirely by her enduring love for him, actually had the effect of making him look a lot less sympathetic.

Peter’s material was another challenge. Most of his work (and almost all the best stuff) was done before he met Lin, and it soon transpired that a great deal of it had actually been written with other people – not only Dudley, but all sorts of other folk who helped him out after Dudley left. The vast bulk of it was Peter’s, but he found it hard to get around to it unless someone else was there to spur him on. Not surprisingly, a lot of these people wanted credits. Some of them wanted money. Apart from a few comic poems, Lin’s promised cache of unpublished material never quite materialised (some of it eventually surfaced in Victor Lewis-Smith’s documentary). As my deadline hurtled into view, I realised I would have to look elsewhere. It was frustrating, but I sympathised. I could see that, for Lin, the strain of being Peter’s widow was immense. No other comic has been so revered and so derided. Both extremes excluded Lin from the story. Maybe that’s why she felt compelled to fight his corner, even about stuff that happened before they met.

My anthology, called Tragically, I Was An Only Twin (one of Peter’s working titles for his unwritten autobiography) did well enough to spawn a sequel, called Goodbye Again, focused solely on the sketches that Peter wrote with Dudley. Later, when I wanted to embark on a biography of Cook and Moore, Lin gave her consent (which I badly needed, to reproduce excerpts from their sketches) on the condition that she could read the manuscript ahead of publication. In the end, she declined to read it, which was probably for the best. I felt it was an affectionate portrait (as did a fair few others) but there was a lot in it about Peter which I’m sure she would have hated.

One memory of her stands out, which I’ve never shared before, and it says a lot about Peter. On my second visit to Perrins Walk, Lin showed me some snapshots of one of their foreign trips together, to Australia. They’d gone to the place where Picnic at Hanging Rock was filmed. ‘And then a really odd thing happened,’ said Lin. ‘Peter vanished! I couldn’t find him anywhere. Then, ten minutes later, he suddenly reappeared!’

‘Have you ever seen Picnic at Hanging Rock?’ I asked her. ‘No,’ she said. ‘Do you know what it’s about?’ I asked. She shook her head. I was about to tell her, but then I thought to myself, why spoil the joke? Most comics are only funny in front of a paying audience, but Peter was always joking. This was a perfect joke, performed with no audience whatsoever, and Lin had brought it with her, quite unwittingly, for me to enjoy, from beyond the grave.

William Cook is the author of One Leg Too Few – The Adventures of Peter Cook & Dudley Moore, and the editor of Tragically, I Was An Only Twin – The Complete Peter Cook, and Goodbye Again – The Definitive Peter Cook & Dudley Moore, all published by Random House.

Comments