It doesn’t take long for an international event of historic importance to fall off the news agenda. Ukraine is still there, making headlines, but soon it will be forgotten as the political drama in Kiev, Sebastopol, the Crimea is overtaken by an unfolding crisis elsewhere. We who live beyond and outwith the situation are encouraged to move on, gawping instead at another horrifying outpouring of human cruelty and misery. But for those forced to stay on and endure it’s not so easy. For them the terror will linger on long after our sympathies have been translated to another scene, another situation.

On Sunday night, Radio 3 took us back 20 years and to Rwanda, where in April to June 1994 the outside world looked on, helplessly, as the Hutu majority sought to massacre their Tutsi neighbours. More than 800,000 Rwandans were killed in just 100 days. This was violence on a scale never before seen, as the Rwandans slaughtered each other with home-made weapons, knives, machetes, anything they could find, and whole communities were savagely wiped out. How have the survivors — and just as much the perpetrators — learnt to live with those memories, and alongside each other? How does a country recover from such self-destruction? What can the Rwandans now teach others about peace and reconciliation — and perhaps, more importantly, about how to look for the warning signs of impending genocide? Zoe Norridge went to find out for the Sunday feature, Living with Memory in Rwanda (produced by Anthony Denselow).

She told an extraordinary story. Every year in April as the rains begin, and life is accompanied by the sound of raindrops falling heavily on lush tropical leaves, the Rwandans are taken back to the rains of 1994 and the day when the violence began, 7 April. Almost everyone we heard from had lost someone close to them, their father, a beloved sister, their mother, brother, wife or husband. Each year, a national week of mourning is dedicated to remembering the dead, but also to looking back into that darkness. ‘It’s very important,’ Norridge was told. ‘We cannot close the chapter of darkness.’

But it was simply not feasible to prosecute all those guilty of the violence — perhaps as many as 300,000. The Rwandans recognised that ‘neither full truth nor full justice was ever possible’. Instead they have had to find different ways of coming to terms with what happened, and moving on. The traditional local courts have brought some of the perpetrators to trial; but many of them are still living just where they always have. ‘Whose side were you on?’ is a question still uppermost in the minds of those Rwandans who lived through the terror. Yet the country has rebuilt itself.

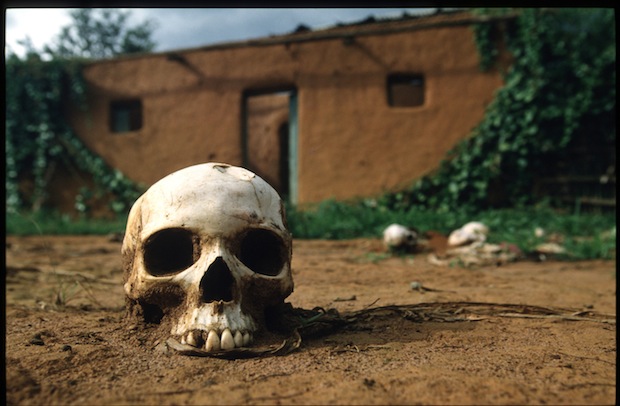

Six national memorials have been set up to collect testimonies from those who suffered, and those who inflicted the suffering. Each has its own horrors to recall. Norridge visited Murambi where thousands of Tutsi took shelter in a technical school, believing they would be safe there, only to be betrayed. ‘The smell is biting,’ she told us as she entered one of the rooms, an intensely chemical smell. Here the bodies of the slaughtered are now on show, eerily preserved, ghostly yet very real. They were exhumed from the hastily dug mass grave shortly after the massacre, and those bodies that had not rotted away completely were embalmed, just as they were when they died. There is no exhibition, no explanation, no commentary. Just the bodies. In the position they were in as they fell. ‘You can imagine how they suffered,’ said Norridge, while her Rwandan guide told us, ‘Come and learn.’

In Three Pounds in My Pocket (produced by Smita Patel, Radio 4, Friday) Kavita Puri explained how her father, like many other Indians, usually men, arrived in Britain from the subcontinent in the 1950s with just £3. The Indian government was so short of foreign currency it rationed the amount anyone could take with them. Puri’s father was 24 when he came, a graduate engineer, keen to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the manufacturing industries here, and the 1948 Nationality Act that allowed Commonwealth citizens to settle in the UK. It was mid-November, grey, damp and chilly when he got off the boat, with one suitcase and no overcoat. He had arranged lodgings, in Middlesbrough, where he had found a job, but when he got there at five in the morning, after travelling on the last train out of St Pancras, the landlady would not answer the door. It was the milkman who saved him, struck by how cold and wet he was, ringing on the doorbell until she reluctantly came downstairs.

Such small acts of kindness were interwoven with the racism and bigotry of 1950s Britain, where some cafés would not allow blacks to enter and it was legal to put up adverts for lodgings that stated ‘No blacks’. Many who came were disappointed by the shabbiness of Britain, the lack of heating, electricity, decent food. As for the £3, what could it buy then? Food and lodgings for just one week.

Comments