There are 1,000 spaces available for the 6-9 a.m. lane swimming session at Tooting Bec Lido in south London. On Sunday it was fully booked. After a few frantic lengths (at 91m, it is Europe’s longest), we are all shooed out at 8.50 a.m. by the lifeguards to make way for the daytime swimmers. Those slots are like gold dust and sell out within minutes of becoming available. Across London it’s the same story: swimming spaces are a precious commodity.

After three heatwaves so far this summer and the warmest June on record for England, it’s easy to see why so many people are craving access to outdoor water. In total, the capital has just 15 lidos (if one includes a couple of ponds). Even the Serpentine is fully booked on good days. When people are queueing up to wade through duck poo it’s hard not to wonder whether maybe there should be more facilities available.

Other cities in Europe are way ahead of us. Zurich and Geneva have their lakes. Paris has opened up areas of the Seine for swimming for the first time in a century. In Munich’s English Garden, one can paddle in the Eisbach (officially verboten, but this is widely ignored, in contrast to the stereotype of strait-laced Germans) or surf on the artificially constructed wave. Even the northern Europeans are at it: Copenhageners are diving off the docks, Amsterdamers are cooling off in the canals and Berliners have more than 50 lakes and pools from which to choose.

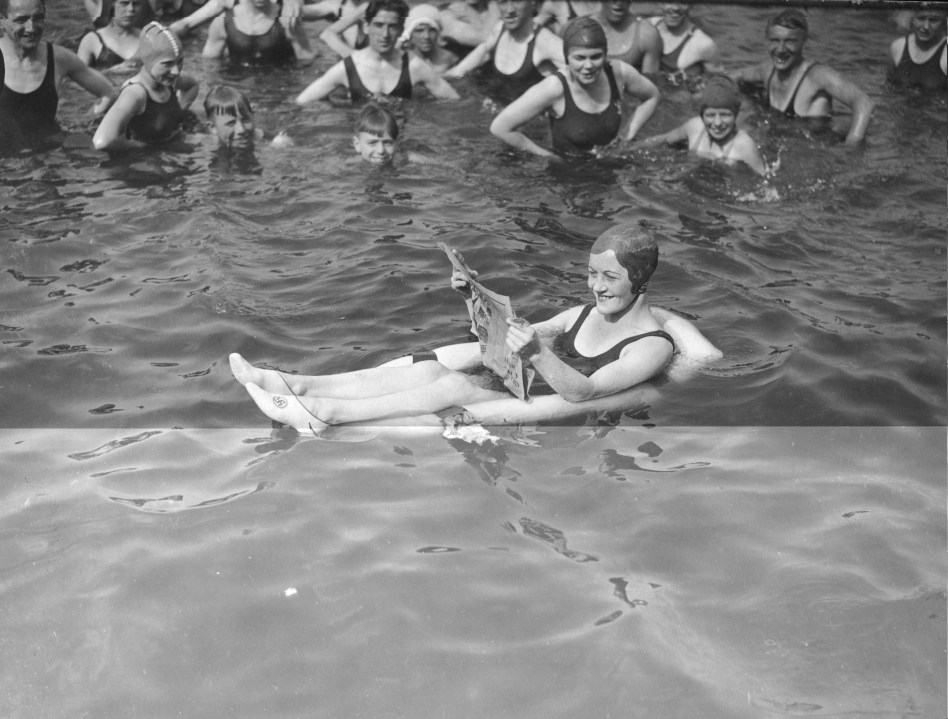

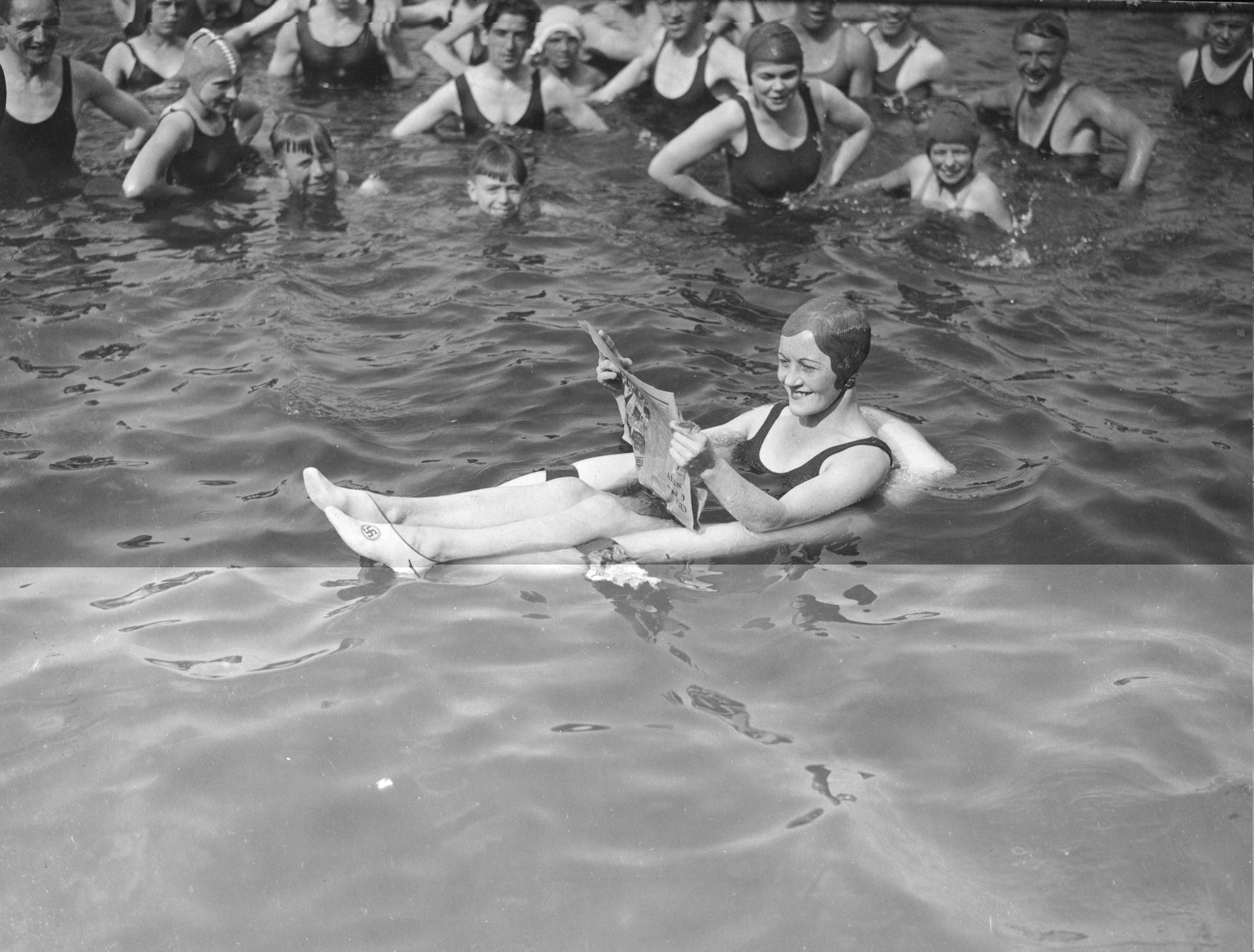

It wasn’t always like this. In the 1930s, the golden days of lidos, London had 68 public outdoor pools. Many were magnificent art deco constructions that became hubs of glamour and entertainment. But with the growth of foreign holidays in the postwar years, the popularity of lidos declined, and the council financial constraints of the 1980s and 1990s meant many closed.

A similar picture is replicated across the country. The website All the Lidos lists 150 or so public outdoor pools across the UK, down from a peak of more than 300. Many cities, particularly in Scotland and Wales, have none at all. (For anyone wanting a more in-depth history of the rise and fall, Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style is on at the Design Museum in Kensington until 17 August.)

But a group of lido evangelists are working to reverse the decline. Future Lidos was set up during lockdown to bring together existing and planned projects, share resources and co-ordinate campaigns. Its co-founder Deborah Aydon tells me that 2023 was a high point, with new pools opening in Hull, Bath and Brighton. It was even dubbed the ‘year of the lido’.

In total, Future Lidos counts 38 different revival campaigns. In Macduff, Aberdeenshire, ‘Friends of Tarlair’ are making progress in redeveloping the art deco pool where Wet, Wet, Wet played in the 1990s. In London, architects Studio Octopi have proposed an ambitious plan to replicate the floating lidos that once graced the Thames. There are also more straightforward options: Battersea, Richmond and Regent’s Park all contain lakes and ponds, but at present their use is limited to the birds. Sadly, most projects tell the same story of wading through the bureaucracy and inertia that seems to make any construction in this country so slow and expensive.

Inspired by various apparent health benefits, and possibly a touch of self-flagellation, thousands of people are visiting unheated lidos in all months

The recently opened Sea Lanes pool in Brighton is doubly notable: as well as being the first new public outdoor pool to be built in the UK since the 1990s, it was fully funded by private investment. Combining seafront swimming with a gym, sauna, pilates and several cafes and bars, it already gets more than 100,000 annual visitors. According to Duncan Anderson, who helped develop the business plan and now runs the centre, it’s a model that could be replicated elsewhere: ‘As long as the council is open to a partnership pools can be built with zero public money.’

It’s not just fair-weather swimming that is rising in popularity, either. London Fields Lido in Hackney is heated all year round; in January you can find bobble-hatted swimmers sliding into the steamy water. Elsewhere, inspired by various apparent health benefits, and possibly a touch of self-flagellation, thousands of people are visiting unheated lidos in all months. At Brockwell Lido in south London – which narrowly survived the 1990s purge through the hard work of local volunteers – I’ve joined throngs of swimmers in sub 8°C water, and hundreds turn out for their Christmas Day swim. Sian Richardson, an enthusiastic year-round swimmer, set up the aptly named Bluetits for like-minded masochists in 2014; today it has more than 150,000 members.

Swimming makes us physically fitter, but it also helps many people with their mental balance. Charles Sprawson, in his superb social and cultural history of swimming, Haunts of the Black Masseur, wrote: ‘Like Narcissus many of the swimmers suffered from a form of autism, a self-encapsulation in an isolated world, a morbid self-admiration, an absorption in fantasy.’ He may have been talking about the Romantic poets who repopularised swimming in Britain, but his words feel fitting for today’s urbanites. Perhaps with more access to swimming, we might be a bit more resilient (working title for the campaign: more dips, fewer PIPs).

The UK is surrounded by water but too few of us have the opportunity to immerse ourselves in it regularly. London could be one of the world’s great swimming cities and lead the nation’s aquatic renaissance. It already has some of the finest parks and lots of natural waterways. There is ample space and enormous demand. Surely it’s time to open up the ponds and start digging the pools. The way things are going we are all going to need a place to help cool us down and keep us sane.

Comments