The greatest myth to affect Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) is the one of his own life: the romantic bohemian who escaped to the South Seas.

The greatest myth to affect Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) is the one of his own life: the romantic bohemian who escaped to the South Seas. This has spawned numerous popular interpretations from novels such as Somerset Maugham’s Moon and Sixpence to films which include Lust for Life (though principally about van Gogh, it features Anthony Quinn as an unforgettable Gauguin) and the Danish–French Wolf at the Door (1986). The danger with such an enjoyable myth as Gauguin’s back-to-nature nonconformist is that it is more than likely to obscure the real merits of the work the artist produced, with great seriousness and at great physical and emotional cost. It’s all too easy to view the work as a by-product of the myth, whereas the extraordinary and compelling originality of Gauguin’s paintings and sculptures are what should place him at the forefront of our attention.

The Tate’s new show, sponsored by Bank of America Merrill Lynch, concentrates on the artist’s narrative impulse, the stories he used as the framework for his beautiful paintings. Decoding symbolism may enhance aesthetic enjoyment, but a liking for the way Gauguin paints, draws and carves, for his genius at making things, has to be the primary response. My advice is to go round this exhibition and simply look: discover what you can see in these great works of art, and whether you like them. There’s plenty of time afterwards to take the catalogue (£24.99 in paperback) home and study it for hidden meanings. The direct experience of looking at Gauguin’s very particular colours and forms can never be reproduced in any publication; for that you have to be there.

The first room in Tate Modern’s supremely uncongenial suite of temporary exhibition galleries contains five self-portraits, ranging from 1876 to 1903, with a classic late figure painting, ‘The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch’. A sixth Gauguin self-portrait, with a section of the ‘Spirit of the Dead’ painting reversed on the wall behind him, ensures we fix in our minds the artist’s progression from stockbroker and Sunday painter to Modern Master. By starting with the man in this way, the myth of the individual is perpetuated. Best to push on into the following galleries in pursuit of the art.

In Room 2 hangs a marvellous painting of a ham, done in 1889, the worn yet blazing orange background flaring against the duller red of the meat and its encircling creamy-white fat. The object pictures in this room are particularly good — look, for instance, at ‘Still Life with Profile of Laval’, the forms of the fruit rhyming nicely with the background patterns. ‘Still Life with Flowers and Idol’ is oddly seductive, but somehow ‘off’, as if the hot-house temperature of the palette has rotted the subject. The emotional complexion of Gauguin’s imagery is often dark, as can be seen from the sinister double portrait of two children. These unsettling depictions (note especially the blank-eyed stare of the right-hand figure) are compounded in the almost demonic and obsessively painted presence of his friend the Dutch painter Meijer de Haan.

Room 3 is given over to documentary material: books, letters, photographs, posters, and so on, intended to give a flavour of the artist’s life and times. Together with Room 8, a similar assemblage, these distractions should be avoided. Obviously, the curators have to fill up all these rooms with something, but with an exhibition of this size, it’s essential to keep your energies for looking at the art. Drawings are in Room 4, and I would direct you in particular to a delicate crayon and pastel ‘Head of a Tahitienne’, and the pencil ‘Study of a Nude’, a powerfully distilled back view.

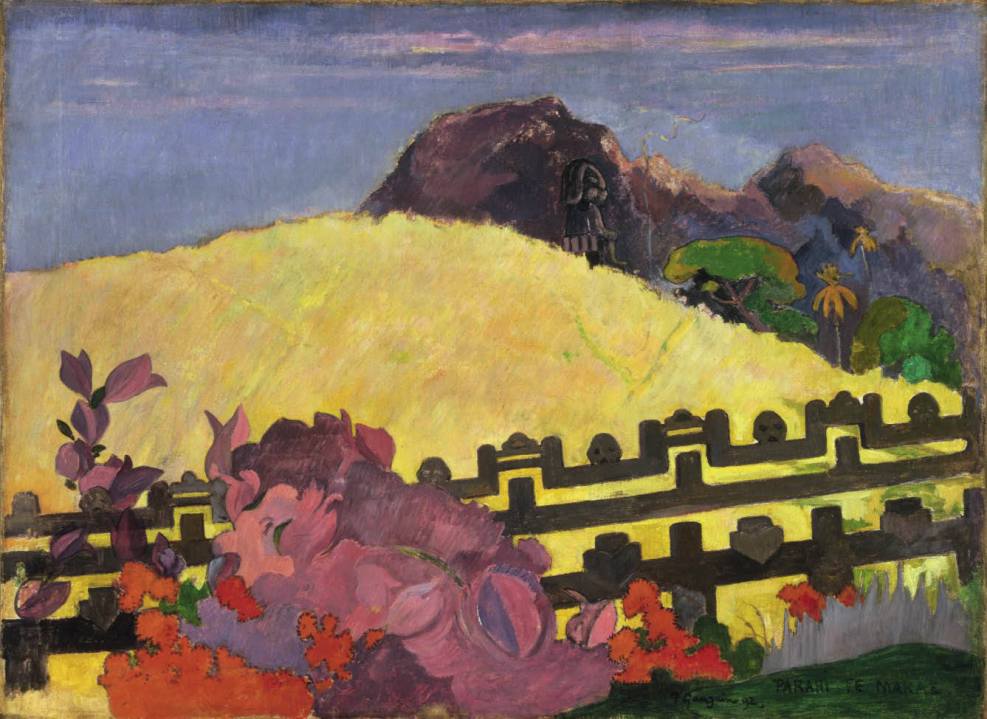

The exhibition really gets into its stride in Room 5, with landscape paintings. Apart from the Courbet-inspired ‘Bonjour Monsieur Gauguin’, with its ill-met by moonlight feel, there are sumptuous paintings of haystacks in Brittany and such old favourites as ‘Tahitian Landscape’ (1891) and ‘Harvest: Le Pouldu’ (1890), in which the combination of pattern and colour, carefully but inventively orchestrated to a descriptive end, sing to the heart and mind. In the midst of these beauties is the brutally symbolic ‘Loss of Virginity’, further evidence of the seam of cruelty that runs through Gauguin’s work. Opposite is a rare Martinique landscape, in which the foliage is composed of long slashing strokes of paint, as if the pigment were not only melting but also chivvied by the elements.

Room 6 contains the great religious paintings: ‘The Yellow Christ’, coupled with ‘Breton Calvary (The Green Christ)’, and ‘Vision of the Sermon’ hanging on the wall at right angles with ‘Christ in the Garden of Olives’. Apart from the obvious and ostensible subject matter of these striking paintings, note the way forms are radically juxtaposed and cropped, colours are deliberately heated or cooled, and compositional patterns direct the eye in new directions. Here, too, are splendid carvings and ceramics, irritatingly labelled not on their plinths but somewhere on a wall nearby. Curatorial fashions in labelling leave a lot to be desired.

Gauguin’s drawings will not be familiar to many, and I was fascinated to see in Room 7 such studies as ‘Mysterious Water’ (1893–4), in gently evocative watercolour and ink. The woodcuts, for Gauguin’s book Noa, Noa, for instance, are much better known, but the carvings are what really repay close attention. Gauguin’s chunky women often work better in the sculptures than in his paintings. For example, the painted relief oak carving ‘Woman with Mango Fruits’ is far more effective than the painting next to it, ‘Delectable Waters’. Here, too, is the great carved gateway for the ‘House of Pleasure’, and such superb polychrome reliefs as ‘Mysterious Water’ and ‘Be Mysterious’.

Room 9 is the hub of the exhibition, a small gallery filled with some of Gauguin’s very best and most lucid paintings: ‘Nevermore O Tahiti’, ‘What! Are You Jealous?’, ‘Where Are You Going?’, ‘Brooding Woman’ and ‘The Ancestors of Tehamana’. Room 10 features a stupendous series of colour woodcuts and another of zincographs on yellow paper. (Overload is imminent.) The final room houses another astonishing group of late Gauguins: ‘Tahitian Pastoral’, ‘The Ford (The Flight)’, ‘Delightful Days’. The facial features may have coarsened and become more bestial, but the colour is every bit as poetic and magical. Meanwhile, ‘Two Tahitian Women’ is breathtakingly lovely. There’s just too much here. Be kind to yourself: somehow find the time and money for a return visit.

PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART

Comments