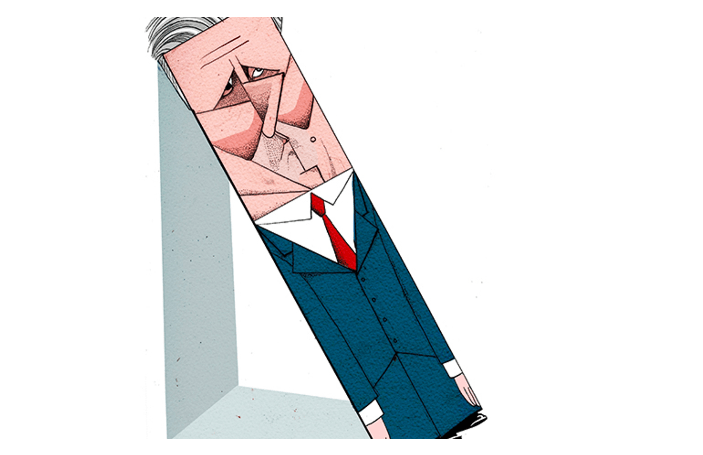

Keir Starmer has been leader of the Labour party for just eight months. But that hasn’t stopped analysts defining what it is that ‘Starmerism’ represents. To some, it is an empty space where ideas should be: technocratic, electorally-driven but otherwise strategically rudderless. Others – most obviously implacable Corbynites – even detect elements of free-market individualism. So what does Starmer really stand for?

Commentators seem addicted to attaching the suffix ‘-ism’ to leading politicians’ names to capture what they are ultimately all about. Too often however this ‘-ism’ gives leaders’ actions a fake coherence. Margaret Thatcher certainly had a clear vision of where she wanted to go when elected Conservative leader in 1975. But what became known as ‘Thatcherism’ was fashioned by the vicissitudes of electoral competition. It was also dependent on events over which she ultimately had no control. What if the Tory ‘Wets’ had put up more of a fight? Or Labour had not descended into civil war? Or if Argentina had not invaded the Falklands? ‘Thatcherism’ was defined by these variables, and more – it wasn’t simply down to Thatcher.

So while ‘Starmerism’ will be defined by the Labour leader’s need to address the reasons for his party’s 2019 defeat and the run of three election defeats that preceded it, he is not completely free to choose how he will accomplish this daunting task. Instead, Starmer has to negotiate a path to power through an electorate firmly divided – as the authors of Brexitland establish – between ‘identity liberals’ and ‘identity conservatives’.

The outlines of ‘Starmerism’ have however barely been drawn

The Red Wall seats did not fall in 2019 just because accustomed Labour voters – mostly white, working class and with a basic education – wanted Brexit done. It was the product of long-term cultural trends. Starmer knows Labour must win back those seats if it is to form the next government by at least gesturing to the concerns of such constituencies. This is why he has talked of wanting to make Britain a ‘country in which we put family first. A country that embodies … [d]ecency, fairness, opportunity, compassion and security. Security for our nation, our families and for all of our communities’. And, as Isabel Hardman suggests, this will remain the Labour leader’s main focus next year.

But the more he emphasises conservative tropes – and, depending on what policy flesh Starmer puts on those rhetorical bones – the greater the risk is that he will alienate younger, university educated metropolitan voters. This group has moved closer to the party in recent elections. But as 2017 proved, Labour cannot win power by them alone.

Even so, their support cannot be taken for granted. The recent Labour Together report nonetheless suggested Labour might be able appeal to both sets of voters. Quite how, will be one of Starmer’s key strategic decisions.

But just now, Starmer is keen to signal as strongly as possible to identity conservatives that the party they rejected in 2019 has changed. That was also a reason why Starmer put rooting out anti-Semitism at the top of his agenda. But how credible his claims of change will be is largely in the hands of Labour members: do they want it?

Starmer was elected leader by a party many of whose members wanted to retain most of the policies contained in the 2019 manifesto. These people also saw Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership in broadly positive terms; some also believed the scale of anti-Semitism in the party was exaggerated.

In his campaign – and since being elected – Starmer has avoided directly challenging these beliefs (with the notable exception of anti-Semitism). This latter issue is now causing him much trouble. His suspension of Jeremy Corbyn from the Labour party has provoked a backlash amongst constituency Labour parties, who have expressed their lack of confidence in Starmer’s leadership. If this is evidence of an entrenched and combative opposition to the Labour leader, which prevents him altering party policy, then Starmer’s message of change to voters will be seriously compromised.

Just as the Winter of Discontent gave Thatcher a critical boost in time for the 1979 general election, Starmer has so far benefitted from the Covid crisis. This unwelcome event highlighted early on his grasp of detail and often remarked ‘competence’, certainly when contrasted with Boris Johnson. Even if voters aren’t yet sure what Starmer stands for, they now see him as a credible candidate for Number 10.

But with Britain having to face up to the unprecedented economic implications of the crisis – and the as yet unknown impact of Brexit – next year will present the Labour leader with even more unavoidable tests. Perhaps, too, he will encounter a revived Johnson – or even a new prime minister – against whom he will have to define himself.

Keir Starmer has made a more than steady start as Labour leader if progress is measured in opinion polls. But the outlines of ‘Starmerism’ have barely yet been drawn. What will Starmerism look like? Ultimately it isn’t up to the man himself, but by the electorate, events and, especially, his own party members. We are only at the start of this particular political journey. Yet the early signs suggest that Starmer has a big fight on his hands.

Comments