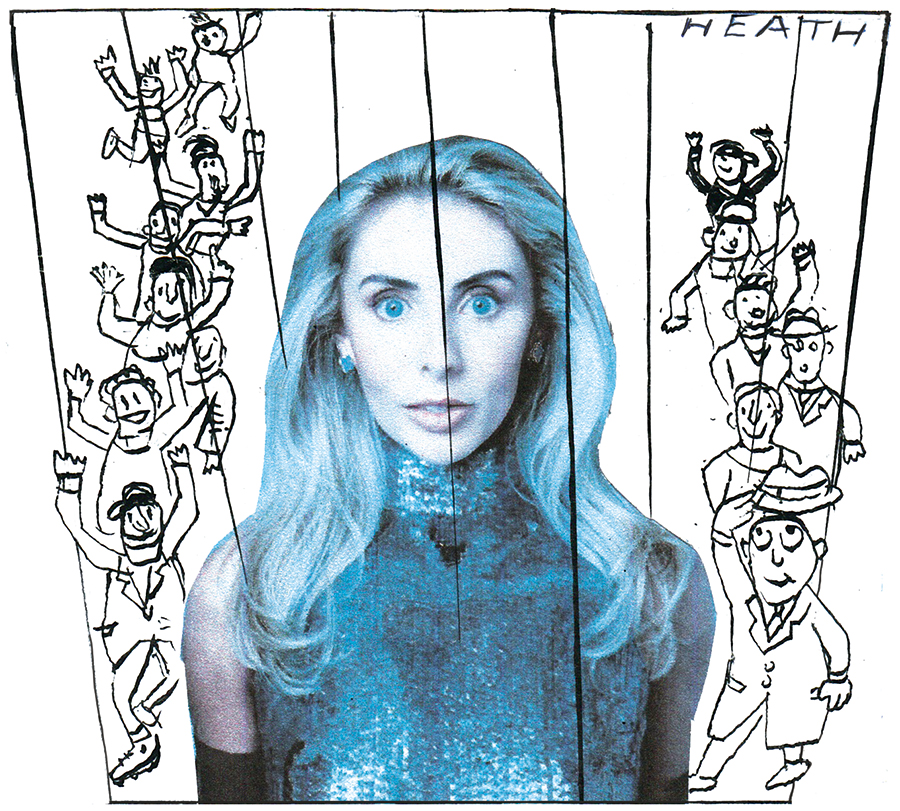

The fantasy of telling disagreeable friends how awful they really are is a relatable one. But rarely does it find such extravagant, relentless expression as in Zoe Dubno’s debut novel Happiness and Love. The narrator is a nameless woman who finds herself among former friends in New York. While she never succumbs to an outburst, her interior monologue issues forth like a furious esprit d’escalier.

The dramatic scenario – modelled on that of Thomas Bernhard’s 1984 novel Woodcutters – is a dinner party in the loft dwelling of an ‘art world’ couple with whom the narrator used to live, following the funeral of one of their cohort. The narrator remains resolutely mute – sitting for much of the span of the ‘story’ (which is really a framing device for her stream of consciousness) on the corner of a sofa watching her erstwhile friends.

The novel’s humour and grim horror are concentrated in the figures of Eugene, a narcissistic artist, and Nicole, his trustafarian curator girlfriend. From the moment the narrator bumps into Eugene in the street after a five-year hiatus he is cast as a ghastly pseud, almost too pretentious to be plausible – his tote bags stuffed full with what he calls ‘texts to fuel his study of object-oriented ontology’. He and Nicole are art collectors, too, of the worst variety – believing that ‘by purchasing the work, that in exchange for handing over the cash, they receive from the artist not only the piece but also the key to what it means, but of course they never do understand the work’. Italics denote reported speech, but also serve the wider function of inverted commas – unmasking the hidden folly of choice words or phrases.

Dubno has a particular talent for capturing the vanity, neediness and delusion of a certain type of wealthy ‘benefactor’ – their desire to be flattered (but not too much) and their gnawing suspicions of the motivations of others. Reading the novel is akin to spending time with a witty if merciless observer of other people’s idiocies. There’s something of a latter-day Holden Caulfield about the narrator in her dissections of Nicole (‘her ridiculous black Margiela mourning costume’) and Eugene (‘motoring along with cocaine long after his faculties of judgment, tact and coordination had been dulled to the point of nonexistence’).

The novel is at its best where its claim to dramatic realism is thinnest. Disembodied voices reverberate with more force than events. The actress who turns up and rails against the assembled party, ventriloquising much of what the narrator herself seems to have felt, is more a choric figure, swooping in to pass judgment, than a character in any classical sense.

If at times the narrative style has the stridency and one-sidedness of a rant, it also possesses an enlivening, claustrophobic charge. Unbroken from beginning to end, the monologue is characterised by a self-conscious chewing over of certain phrases or words or ideas. The device of italics suffers from an overuse that may be intentional, acquiring its own faint absurdity – as though anything and everything were worthy of ironising. Eugene’s demi-monde is eye-rollingly framed, for example, as ‘a new-world downtown, a place full of artists and critics’.

Reading Happiness and Love, one has the rising sense of being trapped in a single point of view – encased in the prism of the narrator’s burning disdain. But this ends up being the novel’s peculiar force. The present-tense setting of the gathering at the apartment (a ‘cathedral of modernist rococo’) evolves into a sort of hell, within which the narrator plays the part of a contemptuous ghost, observing proceedings yet barely noticed. Just when you feel that Dubno – or her character – can’t keep banging the same drum of invective, she somehow breaks through the other side of monotony. The repetitiveness becomes a propulsive refrain, like a delirious anger that feeds off its own momentum.

Comments