In the Easter holidays, plus two school days, for which his mother will be fined or, as a serial offender, she will be summoned to appear in court (not that she’s bothered, bless her), I took grandson Oscar to Provence for a week. The flights cost us nothing because a neighbour passed on his air miles to us, plus an upgrade to Club Europe, which is business class. Grandad was excited about the upgrade because it would enable Oscar to see how the other half lived, and perhaps make his own judgment about whether a slightly wider seat on a plane was worth trying harder at school for. The night before the flight we stayed at a hotel. ‘Why aren’t you at school?’ said the receptionist to Oscar.

Our Club Europe tickets entitled us to use the business lounge. Two and a half hours before departure we showed our boarding passes at the desk. We were both wearing Lionel Messi Adidas football boots. Oscar’s were gold, mine were fluorescent green with red arrows. But it didn’t seem to matter and we were admitted with an indulgent smile, suggesting a fine respect for equality among the elite.

I was so hungry I could have eaten a vegetable. Oscar and I cruised the hot and cold buffet marvelling at the variety and quality of the free food and drink. I piled two plates high with cake, bacon, sweet corn and strawberries. Oscar modestly selected a mini-croissant. The vast quantities of free food seemed to embarrass him. ‘What about a piece of Grace, your cake?’ I said.

The few other occupants of the lounge sat around on nests of low comfortable-looking couches and chairs. A disabled woman from southeast Asia limped between them with a tray and a dishcloth. Nobody spoke. Nobody was interested in their surroundings. Everyone sat there like living sculptures. The uncrossing of a leg or the exploration of a lower nostril with the tip of a forefinger was an event. Rising gracefully to tread the carpet for more victuals and back was an exercise in mindfulness.

Oscar tried hard to find something delightful in all this. Then we both decided that we would rather be trampled underfoot and have to queue and pay for things than sit here for a moment longer. We returned to the crowded terminal floor, which was like a bank holiday funfair combined with a three-ring circus by comparison. The decision to leave had been the right one, we thought.

‘Aha! You must go to private school,’ said a woman at the gate to Oscar. (We business class had been ushered through the gate first.) ‘State,’ I said. ‘Aargh!’ she said. ‘If I’d known the state schools had broken up I’d have booked an earlier flight!’

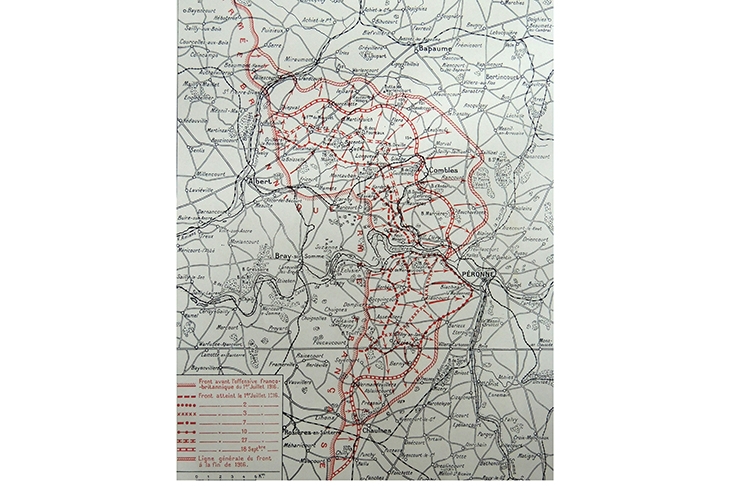

We business class passengers were seated in the first 12 rows of the plane. Oscar and I were in row 11. At my insistence, Oscar resumed his colouring in of his diagrammatic map of the first day of the battle of the Somme.

After take off, a curtain was decisively drawn behind row 12 and a bald steward with a humorous face came round offering a hot, wet flannel between plastic tongs. I took one, telling him (to embarrass Oscar) that this would be my first wash for several days. The bald steward shied like a spooked stallion and held his nose. Then a fat man in front of Oscar, from sheer snobbery, told him that his friend in front of me was a retired circuit judge. The circuit judge was clinically obese. ‘Did he say circuit or circular?’ said someone behind me.

The other steward was an elderly woman. Once the curtain was across, she and Baldy threw off their reserve and handed out wine, spirits and banter by the armful. They were a double act: she mocking his baldness and bachelor state, he how close to death and how unpresentable she was. These two were the life and soul of the party and they quickly gravitated to where they felt their repartee and liberality with the booze was most appreciated. Which was the guy who hadn’t washed and the fat man next to the circuit judge whose stated aim was to drink as much wine as he possibly could in the one hour and 40 minutes.

After being fingered by his neighbour, the circuit judge, however, seemed ill at ease. He had little eyes and kept his little mouth firmly shut. Periodically, and with increasingly bad-tempered resolve, he tried to recline his seat, managing about half an inch, while the bald steward passed spirit miniatures by the handful within an inch of his conspicuously dyed hair like an aid worker in a refugee camp.

Of course Oscar thought it all ridiculous. I leaned across to see how the first day of the battle of the Somme was progressing. ‘La Boiselle,’ I said. ‘You’ve missed out la Boiselle.’

Comments