Talking animals – as anyone who has watched a Studio Ghibli animated film will know – are big in Japan. But not always cute. The snooty hawk, for instance, looks down on the ugly but peaceable nighthawk (‘quite harmless to other birds’), who half-shares his macho name despite a deplorable lack of raptor credentials. Just to humiliate him, Hawk decides to call Nighthawk ‘Algernon’ instead. In despair, the little creature flies up to the heavens, only to be told: ‘One has to have the proper social status in order to become a star.’ The nighthawk awaits a lonely death in the frozen skies but finds his frail body ‘glowing gently with a beautiful blue light’. He has joined the constellation Cassiopeia, ‘still burning to this day’.

If the meek inherit the Earth – and heavens – in Kenji Miyazawa’s luminous fables, they have to pay for it in toil and tears. Miyazawa (1896-1933), who released only a couple of self-published volumes in his lifetime, was both an altruistic soil scientist and a devout Nichiren Buddhist. His Japanese strain of self-help idealism, as he advised poor farmers in his rugged home province of Iwate, recalls the dreams of rustic renewal seeded elsewhere by Tolstoy, Tagore and William Morris. Miyazawa, though, believed that scientific knowledge must fertilise the simple life. Markers of technological modernity – railways, steamers, electric lights, telephone poles – punctuate the eerie folkloric landscapes of these droll, charming but far from naive tales.

Night Train to the Stars collects 25 stories. In the title piece, a child who has to labour in a print shop boards a magical train through the spectacular light show of the Milky Way, the ‘River of Heaven’. As he rides, Giovanni will learn about loss, grief and remembrance in the kaleidoscopic skyscape of this ‘imperfect fourth dimension of fantasy’. Most of the stories feature animals: some have human protagonists, but in this thoroughly Buddhist universe all things claim a soul. Not just ants, flowers, foxes and stars but buckets, dustpans and rat-traps enjoy speaking parts.

Miyazawa fused the ethics of karma with a sort of peasant socialism. Oppressive top-dogs of various kinds meet their come-uppance. Exploited elephants revolt against a brutish landowner, Animal Farm-style; a boss bullfrog enslaves tipsy tree-frogs (they take their revenge); spiders and slugs learn selfishness at Mr Badger’s School but come to sticky ends. In ‘The Restaurant of Many Orders’, a pair of oafish hunters discover prior to a swanky meal (the washroom’s eau de toilette ‘smelled suspiciously like vinegar’) that they are on the menu. A wildcat judge (literally a wildcat) speaks for his creator when he adjudicates between squabbling acorns and decides: ‘The best of you is the one who is least important, most foolish, most ridiculous.’ In another tale, a downcast, third-rate cellist learns from friendly beasts that his music cures sick badgers, cuckoos, mice and rabbits – It’s a Wonderful Life, but with rodents.

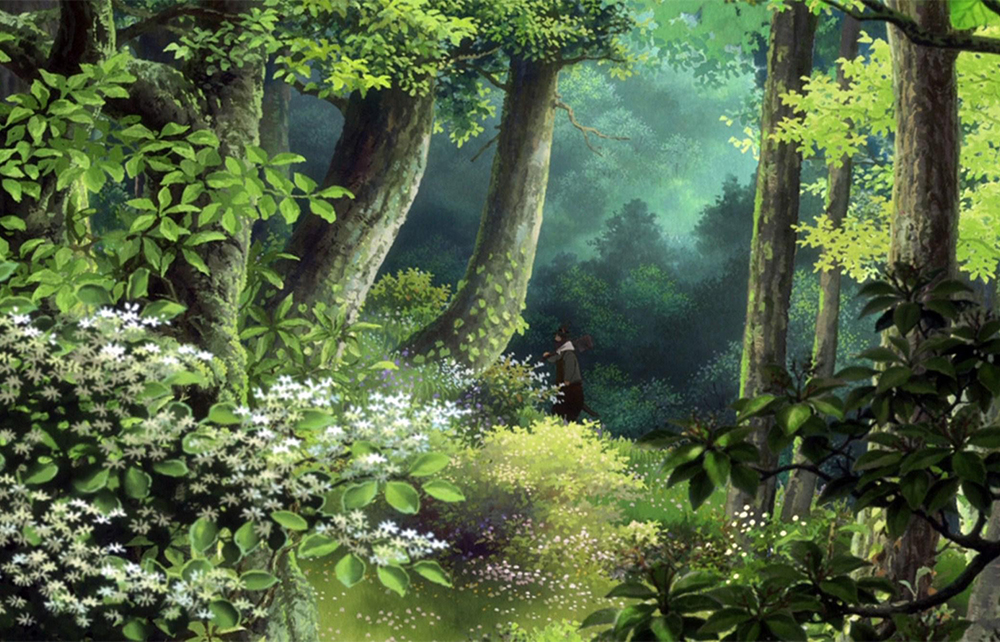

This could all sound twee. But Miyazawa prefers spice to schmaltz, with ironic twists on fairytale conventions. Should we credit the sententious owl’s yarn about how the birds got their plumage just because ‘he looked so honest and reliable’? The mountains, flora and fauna of Iwate spring to life in jewelled prose, informed by a scientific eye. Thanks to the blend of pin-sharp, bright-hued backdrops with outlandish happenings and wholesome messages, Ghibli-movie fans should feel at home. Meanwhile, John Bester’s translations enlist familiar counterparts to Miyazawa’s style – Oscar Wilde, Beatrix Potter, Rudyard Kipling – to find nicely-pitched voices for each tale. I would love to know the Japanese original of the hawk’s crushing put-down. ‘Algernon’, indeed.

Comments