My Budget reaction is mostly: Meh. By that, I mean this won’t really change the weather, though it might just gee up some despondent Tories, who are cheered by the Stamp Duty cut regardless of what the OBR and others have to say about it (in short, it’ll push up prices and only really help people who were already close to buying; it does nothing for the people for whom home-ownership really is a distant dream.)

Perhaps the best encapsulation of this was offered to me recently by a ministerial friend who is not, let us say, ordinarily upbeat about the May Government and its prospects. This afternoon, this governmental gloomster was rather chipper, assuring me: ‘This is good stuff. Real people will like it, whatever miserable geeks like you say.’ That’s probably true, too.

And who knows? Maybe a solid Budget with a decent retail offer will lead to a modest poll bump and cause some Tory optimists to start thinking: ‘You know what, despite everything, we’re still polling 40 percent and Jeremy Bloody Corbyn isn’t pulling away. We can do this. We can turn this around.’ Maybe.

If so, expect the next story from the village to be about the reshuffle, where a resurgent [sic] Theresa May will be urged to be bold and shake things up, bringing in the new talent and setting the Tories on course for an improbable election win in 2022, presumably under new leadership. Perhaps she could transform herself from a John Major or IDS figure into Michael Howard, the stable hand on the tiller who saw the party through choppy waters and handed the captaincy over to a younger generation of winners. Perhaps.

That’s all wild speculation, of course, and my money is really on this Budget not being transformative of anything at all. The weird, tense stand-off between No 10 and No 11 continues with no winner, and thus no really brave policies on housing or the public finances. And the Tory party continues to think that keeping Mrs May as PM is the least bad of the many bad options on offer. So her government, weak but improbably rather stable, will endure.

This is not to say there wasn’t important stuff in the Budget. There was, just no-one will talk about it. I’m referring to productivity, which is bad. Simply, British workers don’t produce enough stuff for every hour they work. We’ve lagged behind the French and Germans here for years, but the problem is getting worse.

Hence the OBR growth downgrades that should be the real story of the Budget. My quick calculation is that those downgrades mean the UK economy will be £49 billion smaller than it would be otherwise by 2021/22.

And that, as I’ve noted elsewhere with my Social Market Foundation hat on, is bigger than Brexit, in more ways than one. Narrowly speaking, £49 billion is more than the Government will spend settling our EU divorce, though the numbers aren’t really comparable.

More broadly, I reckon poor productivity isn’t just a bigger challenge to the UK than Brexit, it’s probably a cause of it too. By that I mean that the British economic model that sees many people working in relatively low-skilled and therefore low-waged jobs plays a significant part in the feeling some people have that this country and its economic-political settlement does not work well for them.

An economy with higher productivity, I think, would be better able to deliver higher-waged jobs for higher-skilled workers, and maybe even allow the wealth created by their work to be spread more evenly around the country, easing the economic skew towards London, the South East and other highly-educated and highly-paid cities that also helps explain the Leave vote.

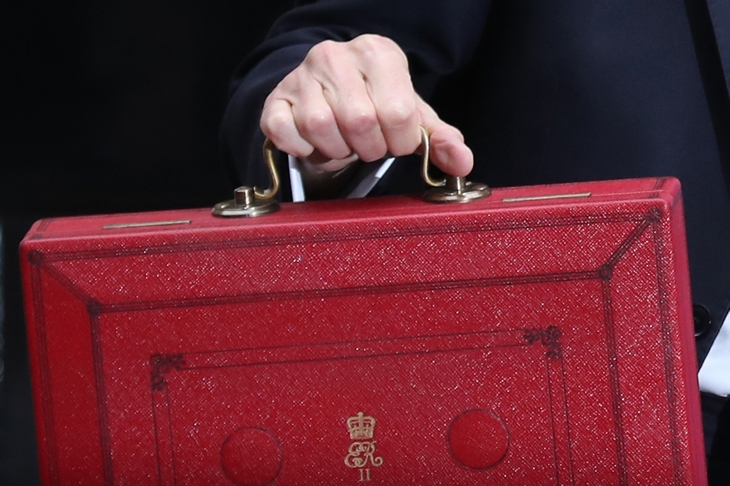

To give Philip Hammond his due, he appears to understand this, and so he said a few worthy things about productivity including some sensible-sounding stuff on R+D tax credits.

But there’s much, much more to do. There’s a huge and largely unexplored territory around competition and corporate behaviour that needs urgent attention. Big incumbent companies don’t face enough competitive pressure from new challengers, which means they feel they don’t need spend spare cash on better deals for consumers or investing in equipment and training and other productivity-boosting goodies.

And pretty much our entire approach to education needs to be revisited, at the level of culture as well as policy. Instead of elevating university arts and social science graduates (yes, I am one too), we should laud engineers and scientists, and regard apprentices as deserving as much (or more) respect as Oxbridge types. The HE sector is ripe for disruption, and should face real pressure to do far, far more to turn out graduates with technical skills. That pressure should include the possibility of more of HE’s public money going to Further Education and technical education.

And Westminster’s shameful refusal to even talk about FE and technical (because let’s face it, People Like Us don’t go to FE colleges and we don’t want our kids to go to FE colleges) should end, now. And I mean journalists as well as politicians: ‘education’ means a lot more than schools and universities, colleagues.

In short, lots of the things that make British productivity weak also make life in this country pretty tough for many of the people who voted to Leave. And the policies that could do a bit to lift that productivity might just make life a bit better for some of those people – and that will be true regardless of what sort of Brexit we end up with.

Comments