It’s been a year to forget for Emmanuel Macron and Olaf Scholz. The German Chancellor’s coalition collapsed last month and on Monday he lost a confidence vote in parliament. Elections are now likely in February. The President of France has had a few election issues himself, as a result of which Macron is on his third prime minister in six months and his personal approval rating has sunk to a new low.

Politically, economically and socially, Germany and France are in crisis and no one is benefiting more than Ursula von der Leyen. The president of the EU Commission, who was elected for a second five-year term in the summer, is now the de facto leader of Europe.

Von der Leyen no longer pays much attention to Macron

In October, von der Leyen ignored opposition from Scholz to introduce five-year tariffs on electric vehicles made in China. Macron was in favour of the import duties (up to 35.3 per cent) but a few weeks later it was his turn to be brushed aside when the EU president flew to Uruguay to sign off the Mercosur trade deal with a number of South American countries.

On this occasion it was Scholz who was satisfied. He hailed a deal that will benefit Germany’s automobile and chemical industries. Macron was livid, as were French farmers, who fear the trade agreement will leave them impoverished.

It was the second time in three months that von der Leyen had put Macron in his place. In September, she told the President to pick a new French commissioner for the EU because the existing one, Thierry Breton, was not to her taste. Macron did as he was told.

It must be a bitter humiliation for Macron. He was von der Leyen’s mentor in 2019 and without his support the German would not have become EU Commission president. He saw in von der Leyen someone who shared his economic and social liberalism, and, more importantly, a woman who would be in his pocket thanks to his endorsement.

The favourite for the EU Commission president’s job had been Manfred Weber, but allegedly his conservative views didn’t sit well with Macron. Weber had been one of the few prominent German politicians who dared question Angela Merkel’s decision to throw open Europe’s borders in 2015. ‘It simply can’t be that refugees in their hundreds of thousands are wandering uncontrolled through Europe,’ he said at the time.

Weber’s view is now shared by most governments in the EU; only the leaders of Spain and France continue to turn a blind eye to mass immigration.

Macron’s indulgence has infuriated the French, who are overwhelmingly opposed to the unprecedented numbers of illegal and legal migrants who have arrived since 2017. He has broken repeated promises to address the crisis, as he has to deport unauthorised immigrants. In an interview in 2019, the President assured the country that soon 100 per cent of deportation orders would be executed; in 2024, the figure stands at 7 per cent while the the EU average is 30 per cent.

Von der Leyen reportedly wants to increase this average in 2025, an ambition that is likely to bring her into conflict once more with Macron. He and his centrist MEPs are united in their opposition to what have been called ‘return hubs’. Currently, a rejected asylum seeker can remain in the EU country until a deportation order is executed but von der Leyen plans to set up facilities outside the EU where they can be held until their removal.

Macron and his centrists regard return hubs as inhumane. Giorgia Meloni does not. At the start of this year, the Italian prime minister said her goal was to ‘block the departures in Africa, evaluate the possibility to open up hot-spots there to establish who has the right and who does not to come to Europe’.

Now von der Leyen is on board. In October this year, she wrote to the EU leaders to urge them to ‘explore possible ways forward as regards the idea of developing return hubs outside the EU’.

Humanitarian organisations were furious; Amnesty labelled the proposition ‘shameful’. Macron let it be known that he also finds the idea distasteful. An Elysee spokesman said he preferred an ‘orderly discussion [on the migrant crisis] that respects international and European law.’ These objections have been ignored and von der Leyen will introduce measures early next year to make it easier to deport illegal migrants.

It is another indication that von der Leyen no longer pays much attention to Macron. ‘She has been disappointed by his actions,’ according to one MEP from von der Leyen’s centre-right European People’s Party.

It is the mismanagement of France’s finances that has particularly appalled von der Leyen. Macron came to power in 2017 with a promise to radically overhaul the economy; at the time, the country’s budget deficit was 3.4 per cent of GDP and the new president said he would meet the EU’s 3 per cent ceiling by the end of the year.

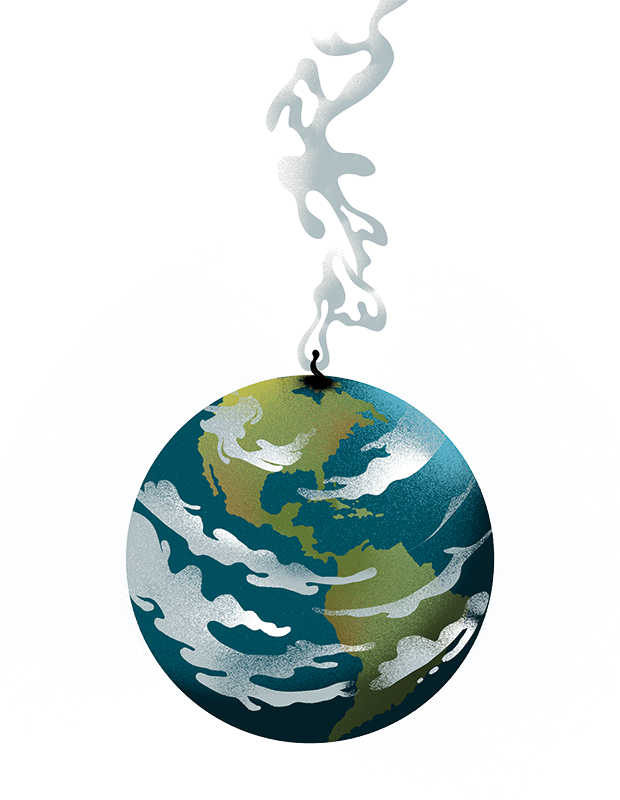

France’s current budget deficit is 6.1 per cent. This prompted the governor of the bank of France to warn on Tuesday that ‘if our country were to remain in budgetary denial…it would risk a gradual economic and European collapse.’

Macron has made France all but ungovernable through his incompetence and now he threatens to bring chaos to Europe. Is it any wonder that von der Leyen is increasingly presiding not just over the EU but also France?

Comments