World championship match play has a stony logic, where there are no prizes for glorious endeavour. It calls to mind the old joke about two hunters who encounter a bear. One puts on his running shoes. ‘You can’t outrun a bear,’ objects his friend. ‘I don’t have to outrun the bear, I only have to outrun you.’ After beating Ian Nepomniachtchi in December, Magnus Carlsen reflected on his experience of winning five world championship matches. ‘I managed to stay relatively process- and passion-driven against Anand in 2013, while in the last four matches it has been all about results.’

Those months consumed by a single opponent surely take a toll on the psyche. In Carlsen’s words, ‘the negative has started to outweigh the positive, even when winning’. He took the unusual step of declaring that he might not contest another match, unless his opponent were from the next generation (the most plausible candidate being 18-year-old Alireza Firouzja, currently ranked second in the world). But would he really contemplate abdication, in case an older challenger qualifies in July 2022? I struggle to believe it.

In the meantime, Carlsen has declared a new goal: 2900. Such a lofty international rating is as daunting as Everest itself. Even for the world champion, it will demand redoubled effort against every single opponent. In January, Carlsen took first place at the elite Tata Steel tournament in Wijk aan Zee with 9.5/13. But since he already outrates all of his opponents, that commanding score was but a small step towards his target, inching him up from 2865 to 2868. The air is thin up there, and every step forward makes the next step harder still.

The former world champion Vladimir Kramnik estimated his chances at around 10 per cent, which strikes me as a fair assessment of the scale of the challenge. It would be a huge accomplishment for Carlsen even to retrace his own peak rating (2882, reached eight years ago). Then again, games like this one, played in Wijk aan Zee, make anything seem possible. Airy sacrifices of a pawn and then rook for bishop quickly create insurmountable difficulties for the Dutch no. 1.

Magnus Carlsen–Anish Giri

Tata Steel Masters, Wijk aan Zee 2022

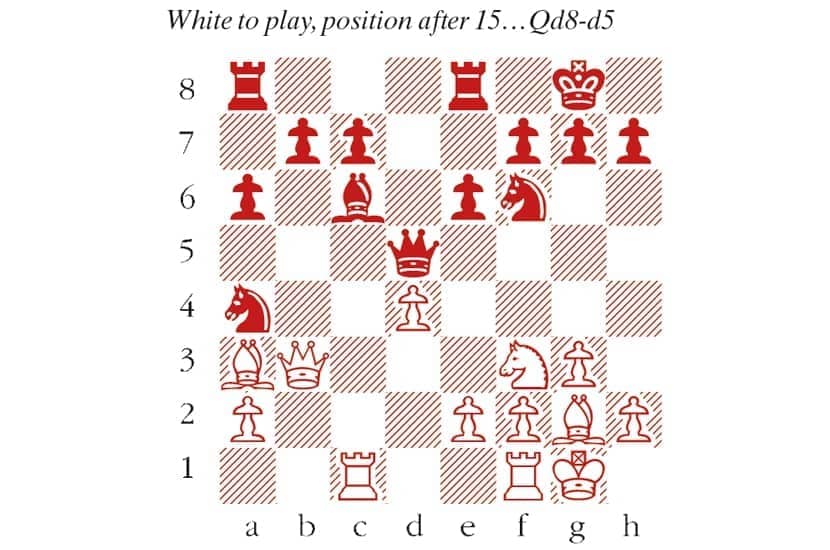

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 d5 4 g3 Be7 5 Bg2 O-O 6 O-O dxc4 7 Na3 Bxa3 8 bxa3 Bd7 9 a4 Bc6 10 Ba3 Re8 11 Qc2 Nbd7 12 Rac1 a6 13 Qxc4 Nb6 14 Qc3 Nxa4 15 Qb3 Qd5 (see diagram) 16 Rxc6 Qxc6 17 Ne5 Qb5 18 Qc2 Black’s problem is that the queen on b5 is awkwardly bound to the knight on a4. Nd5 The best defence was extremely hard to spot: After 18…Nb6 19 Bxb7 Nc4! Black survives. But even there, after 20 Bxa8 Nxa3 21 Qc6! the wayward knight on a3 means Black isn’t out of danger. 19 Rb1 Qa5 20 Bxd5 exd5 Now Black is lost. The lesser evil was to write off the knight on a4: 20…Qxd5 21 Qxa4 f6 22 Nd3 Qxa2. The bishop and knight have lots of loose pawns to aim at, so they slightly outweigh the rook and two pawns, but there is all to play for. 21 Rxb7 The chief threat is to trap the queen with Ba3-b4, and 21…Nb6 22 Qxc7 only makes things worse. c5 22 Qf5 Rf8 23 Nxf7 Qd8 23…Qe1+ 24 Kg2 Qxe2 25 Qxd5 sets up a smothered mate threat to which there is no good answer: 26 Nh6+ Kh8 27 Qg8+ Rxg8 28 Nf7 mate. 24 dxc5 Qf6 25 Qxf6 gxf6 The endgame brings Black only temporary relief. 26 Nh6+ Kh8 27 c6 Rfc8 28 c7 Nc3 29 Bb2 d4 30 Nf7+ Kg7 31 Nd6 Kg6 32 Kf1 Nb5 33 Nxc8 Rxc8 34 a4 Nxc7 35 Bxd4 Ne6 36 Be3 Black resigns

Comments