People go to exhibitions for different reasons, and although I was highly critical of David Hockney’s recent show at the Royal Academy, I accept that a great many people visited it and came out smiling and uplifted. They tended to be individuals who don’t usually go to exhibitions or look at real painting, and it may thus be said that they had very little idea of what they were actually looking at, or indeed should be looking for in an exhibition of painting, but if the experience made them happy, where’s the harm — you may ask — in that? Undoubtedly a great many went because it was the thing to do, and they felt better for being able to say that they’d been there and done that. There is much emotional reassurance to be derived from a group activity of this sort, and it should not be mocked, though it has precious little to do with art. As Anthony Burgess observed: ‘Art is rare and sacred and hard work, and there ought to be a wall of fire around it’; though nowadays it is often confused with spectacle. Damien Hirst (born 1965) has benefited enormously from this lack of distinction.

An inspired curator and a self-promoter and salesman of genius, Hirst has regaled the art market and the media with a constant series of stories and stunts that have pushed his personal celebrity and his product ever higher. A conceptual artist, he’s had some memorable ideas for installations that deal with life and death, explored principally through the preserved carcases of animals. Most of his other ideas are banal, but the marketing skills of the team he employs are so effective, and the media in general so willing to endorse the delusion that Hirst is a major artist, that his work has been hyped beyond belief. So much so that it is now the subject of a major retrospective at Tate Modern (not Tate Britain, of course, because Hirst is an international brand), and is even supposed to represent our cultural achievement for the Olympics. Strange, then, that the Tate show should be so unspectacular as to seem dull, when it’s not actually looking tawdry.

The spot and spin paintings scarce merit a mention, the ashtrays and pills point a very simple comment on contemporary society, and only the sad, dopey butterflies, hatching out in the Tate and dying there before being de-winged so that their most decorative body parts can be made into mock stained glass, seem to offer a parable for contemporary art. It’s highly revealing that Hirst refers to his ‘artworks’, rather than paintings, installations or sculptures. ‘Artwork’ actually means the illustrations for something printed, and up to now has been most commonly used in advertising. Recently hijacked by the less literate members of the art world, it’s assumed to mean ‘work of art’, but actually it hasn’t lost its advertising gloss. Artwork is about marketing and so is Damien Hirst. The last room of his show makes this abundantly clear: a shop in which Hirst merchandise may be purchased, from elaborate silkscreen prints at more than £30,000 to humble postcards, from butterfly-printed deckchairs to spin umbrellas, sterling-silver pill cufflinks, butterfly bone china or skateboards.

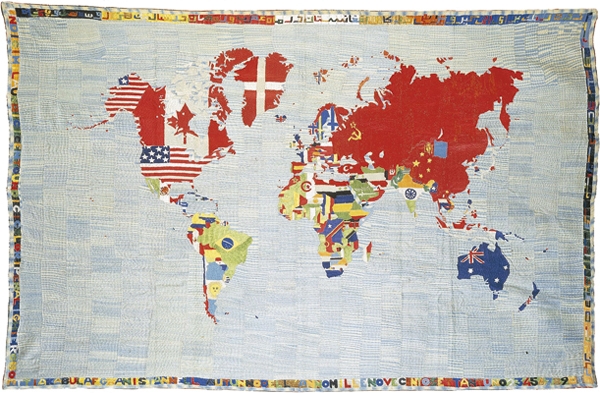

By contrast, the exhibition of work in various media by the influential Italian artist Alighiero Boetti (1940–94) looks marvellous, though it, too, is marred by too much arid conceptual material. The show starts to get interesting with 100 embroidered panels entitled ‘Order and Disorder’. The best of Boetti’s work is related to fabric in some way — the Biro drawings composed of parallel lines of different densities that look woven, a rather beautiful large café-au-lait embroidery on linen from 1979 called ‘The Hour Tree’, or the brightly decorative maps. The latter may document the political shifts during the Cold War, but their primary impetus and appeal is aesthetic. Like Hirst, Boetti only determined how a thing should look and then had it executed by assistants, and I still think art loses much of its resonance and meaning by such deputising. However, in the last room of the exhibition a vast embroidered collage entitled ‘Everything’ certainly highlights the seductiveness of his methods.

Altogether more worthwhile is an exhibition of new paintings by Arturo Di Stefano round the corner from Tate Modern, at Purdy Hicks Gallery in Hopton Street. Di Stefano was born in Huddersfield in 1955, of Italian parentage, and lived in Italy as a child for a couple of years before returning to England, which has been his home ever since. He studied at Goldsmiths and the Royal College and has established a solid reputation as a painter of predominantly urban subjects in the tradition of Sickert and Kitaj, but with a sophisticated Italian edge that looks back to the Renaissance as much as to the achievements of Modernism. Actually, his work is much more subtle and complex than such a sketchy outline can convey, and the current exhibition of new paintings marks a high point in a very interesting career. The show is accompanied by a well-illustrated catalogue with a perceptive text by the poet Jamie McKendrick.

Di Stefano sometimes paints portraits, but more often he suggests the presence of people in his pictures by concentrating on aspects of the buildings they inhabit and the thresholds they cross. He paints doorways and arcades, corridors and staircases and balconies. These architectural features are usually deserted, uncluttered by demanding humanity, and sometimes they begin to dissolve at the edges, as in a dream. This is partly to do with Di Stefano’s technique, which involves painting thinly and then taking a counterproof of a painting while it’s still wet, thus transferring paint from the canvas to a sheet of paper and, in the process, gaining a new image. A beautiful oil-on-paper counterproof entitled ‘Rose’ greets the visitor to Purdy Hicks, a subtly sexualised drapery study of considerable presence, enhanced rather than diminished by its slightly worn and abraded appearance.

In ‘Cloisters, Ferrara (II)’, the solid contours begin to smudge and waver, the columns to lose their substance and become semi-transparent, ghostly. Nothing is quite as straightforward as it seemed: appearances are threatening to fade, as if this corner of reality is a bit tatty, tarnished, used-up. Di Stefano’s paint surfaces are wonderfully variegated, richly scumbled to give a distressed time-worn effect. Notice the disturbance of what you might assume to be the placid surface of ‘Arcades, Bologna’: another pattern of marks is superimposed on the record of appearances like smoke, or water run over glass. In ‘Villa D’Este’ the paint flares like flame in a draught, young and full of life in its depiction of this historic building. Downstairs a study of St Paul’s offers a very different mood, more literally representational and Sickertian, contrasting with the lovely lucid abstractions of ‘New England Nocturne’. And the exquisite ‘Lantern’ casts a tripled lambency before and beyond a gridded window. Magical.

Comments