One September day in 1649, in the frontier town of Springfield, Massachusetts, Anthony Dorchester returned from church to the house he and his wife shared with a couple called Hugh and Mary Parsons. He went to check on a cow’s tongue he was boiling for dinner but to his surprise it wasn’t in the pot. He searched high and low but couldn’t find it. Mary told him that her husband had sneaked off mysteriously on the way to the meeting house and was now nowhere to be seen. Given that the two men had argued about possession of the tongue, the obvious conclusion would surely be that Hugh had stolen it. But for Dorchester and his neighbours a more plausible explanation was that Hugh had made it disappear through the ‘juggling’ of witchcraft. And witchcraft was, of course, a capital crime.

It is dizzying to see the trivial details of everyday life escalate so abruptly into trauma. Eighteen months later a woman called Hannah Langton was cooking a bag-pudding — a concoction of offal and oats stuffed into muslin — but when she opened it she found that it had split from one end to another. Once again a trivial culinary setback was attributed to witchery.

Malcolm Gaskill is excellent at exploring the pressures that could produce such extreme reactions and lead to the Parsons facing the charge of witchcraft. On the one hand, this God-fearing community found itself in the middle of a wilderness populated by wild animals and pagan Indians. Counterbalancing this vulnerability was the claustrophobia of small-town life, where people got to know each other’s fads and foibles only too well, and where jealousy and suspicion could readily ramp up out of control. Hugh Parsons, a brick-maker by trade, was a sulky, taciturn man who constantly thought he was being cheated by his fellows over the everyday transactions of his business.

In the final American witch crisis, the Salem outbreak of 1692, one of the accused was charged with showing no emotion at the ‘suffering’ of the afflicted girls. ‘You do not know my heart,’ she replied, which one way or another gets to the nub of the matter. Exactly the same accusation was levelled at Hugh Parsons when he failed to weep at the death of one of his children. He answered that he refrained from expressing sorrow because of the weak condition of his wife. This was a community that found any sort of emotional repression or attempt at privacy a threat. Genitalia were referred to as ‘secrets’; Parsons demanded to check his wife’s body for ‘witches’ teats’; while he slept she lifted his night shirt and examined his.

Gaskill quotes a sceptic from Tudor times who described witches as ‘harmless melancholics’, a label that fits Mary Parsons to a tee. It is hardly surprising she was a depressive when, like so many women of the time, she watched her own children sicken and die. If witchcraft could cause cows’ tongues to vanish and bag-puddings to carve themselves, then surely it must be responsible for the ravages of disease. Mary came to believe that she had been blown on a mysterious wind to cavort with her husband in a witches’ sabbath.

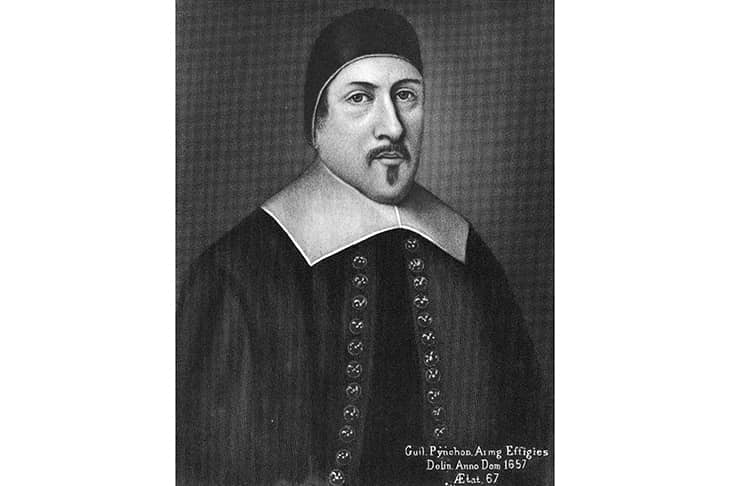

Ironically this troubled township was presided over by a man who comes over as a model of rationality. William Pynchon (an ancestor of Thomas Pynchon, the novelist) was a shrewd but fair-minded businessman who didn’t believe in persecuting the neighbouring Native Americans (not least because it would have a harmful effect on trade). He objected to the harsh Calvinism that prevailed throughout Massachusetts, and wrote a book arguing for a more tolerant and inclusive form of Christianity.

As a result he found himself on trial for heresy in Boston at the same time as his two fellow townspeople were being charged with witchcraft. Gaskill makes much of this coincidence, though it would have been neater in narrative terms if Pynchon’s tolerance had extended to the Parsons themselves. As it happened, however, it was he who undertook their preliminary interrogations and decided that there were charges to answer. Indeed he conducted their prosecutions in Boston while on the receiving end of judicial proceedings himself.

Gaskill begins his book as if it were a novel: ‘Once, beside a great river on the edge of a forest, there stood a small town.’ This approach can at times be problematic. As he says, witchcraft is ‘suspended between fantasy and reality’, so his occasional fictive touches — ‘Hugh’s heart thumped hard and fast’; Pynchon ‘shook the cramp from his hand’ — can disturb that complex balance. But overall this is an impressively researched account, bringing to life the fears and preoccupations of obscure and humble people, and setting them in the context of their time and place.

Comments