Matt Hancock, the business and skills minister, addressed the Resolution Foundation’s low pay debate this morning, an indication of how seriously the Tories are taking the rising cost of living. He delivered a resounding defence of the minimum wage. He said that the evidence was overwhelming: the minimum wage did not harm employment levels: and declared that the Conservatives should ‘strengthen’ the minimum wage. He said that the minimum wage should be enforced, and hinted that the Low Pay Commission might be reinforced. He said that working more hours was not necessarily the right answer, contrary to those who hold that Britain needs to harder and longer.

Beyond that, Hancock proposed a three-pronged scheme: welfare reform to encourage work, lower direct taxes and raised skill levels. He believes that the Conservatives are best placed to deliver this, vowing that the ‘centre-right was prepared to take on vested interests in delivering better skills and education.’

Hancock argued that welfare reform encouraged people into work, adding also that higher pay would also mean less welfare support from the state. He said that increasing the personal allowance has cut tax paid by minimum workers by 75 per cent (although it should be noted that more take home pay is not in itself a solution to low pay). And he said that higher skill levels led to higher wages.

This last point was linked to the wider issue of productivity in the economy, which lay behind much of the discussion that followed Hancock’s remarks. Why is it that median pay went nowhere during the 2003-08 boom? There were various answers from Hancock and his fellow speakers, including Allister Heath and the TUC’s Nicola Smith, and from the audience; but there was precious little consensus.

Tim Montgomerie has tweeted that the ‘hole in #lowpaidbritain session is any reflection on family breakdown. Erosion of social capital has welfare, educational, economic results.’ That is true; but it was not the only hole. There appears to have been very little emphasis on the importance of lowering inflation to reduce the cost of living.

RPI would suggest that prices have risen by 17 per cent over the last four years, while real wages, for instance, fell by 2.9 in 2011. And this does not merely apply to the low paid; it also applies to those on low incomes: the average cash ISA has accumulated just 2.2 per cent interest. RPI inflation is forecast to stay at 3.5 per cent for some time, while interest rates and pay rises are likely to remain flat. The fight against low pay, and indeed modest to decent pay, will have to be ferocious if living standards are to be maintained.

I’ve recently been reading about the economic policy of the Thatcher and Major governments; and I’ve been struck by how far inflation has receded from our public discourse, especially from Conservative rhetoric. Howe, Lawson, Major, Lamont and Ken Clarke thrived and failed by inflation. Indeed, as Norman Lamont observed in his memoirs, the only thing to be said for the disastrous ERM was that it collared inflation.

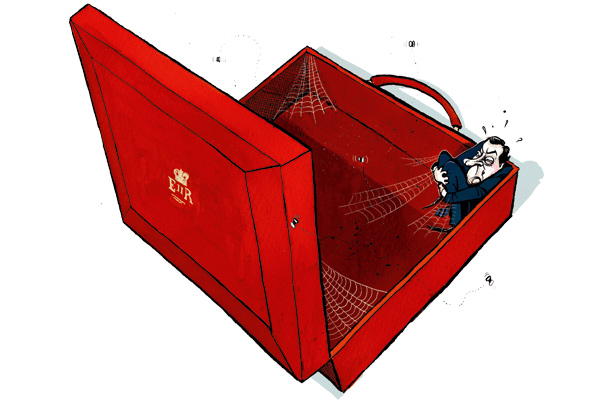

You rarely hear such concerns now. The Tory leadership’s reticence is not surprising, given that George Osborne has raised VAT and continued quantitative easing. As Fraser noted in his pre-Budget cover piece (pictured above), QE has left the poorest two million worse off by an average of £310, which accounts for a fair amount of the dividend from the tax allowance increase. All of this leaves the government vulnerable to the charge that it has contributed to the rising cost of living; and perhaps this is why it has renewed its interest in low pay. Maybe those on low fixed incomes will be next.

Comments