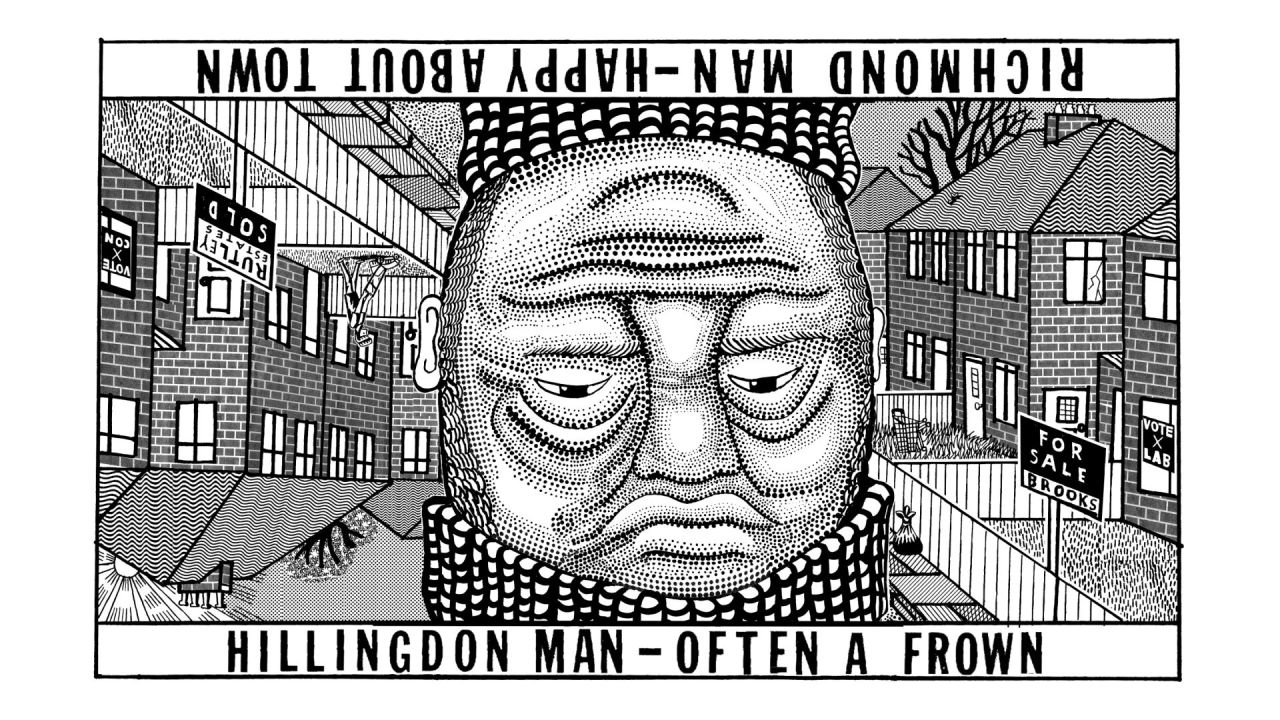

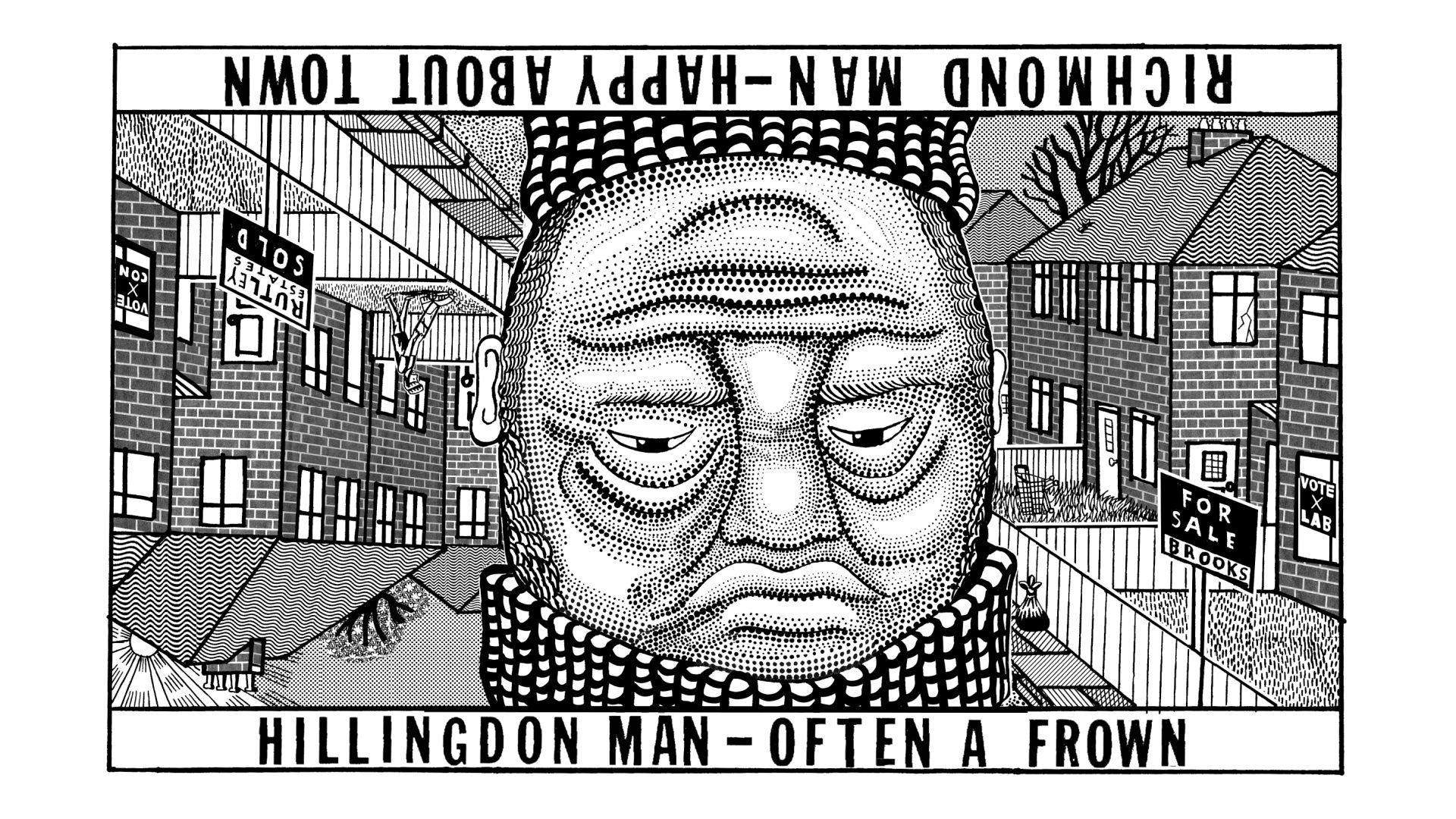

It’s official. I live in the unhappiest place in Britain. Who says so? My neighbours here in Hillingdon, that’s who. They’ve been polled by the property company Rightmove, along with citizens the length and breadth of the country, and Richmond came top(seems money can buy you happiness, after all) while my own London borough, Hillingdon, a few miles away, came rock bottom.

For me, this was a complete surprise. In 2011, my wife and I moved to Hillingdon, from insufferably trendy Chiswick to profoundly unfashionable Ruislip, and we’ve never been happier. We raised our two children here, and even though they’re now both away at university they return home whenever they can.

What’s so good about living here? Well, we could actually afford a house, rather than being cooped up in a flat in Chiswick. Our children loved having a garden to play in, playing fields right on the doorstep and woods and meadows nearby.

People used to grow up and get married and raise a family and grow old here. No longer

Our neighbours seemed to like it too. When my daughter started at the local primary school, just around the corner, we met lots of parents who’d been to the same school themselves, even a few grandparents too. It was the same story when my son and daughter went to local comprehensives. Finally, we’d found a community in London that spanned several generations. Who knew?

We soon got to know our neighbours. It felt strange (and rather nice) knowing virtually everyone on our street, not like the London we used to know. Having good neighbours turned out to be a lifesaver. When my son went down with meningitis, I knew the lady who lived across the street was a nurse. I hammered on her door at dawn. She rushed over the road, gave an instant diagnosis and commanded an ambulance to come immediately. She saved his life.

The street where we used to live in Chiswick had been lively but anonymous. Sure, sleepy Ruislip and the surrounding suburbs were a bit boring by comparison, but they felt like villages, rather than part of London. Yet with three Tube lines within walking distance, it was easy to get into town.

So why are so many of my neighbours so unhappy? After 13 years in the neighbourhood (an era that has coincided, more or less, with the current government), I reckon the root of it is house prices.

The reason Hillingdon suburbs feel like villages is because until a century ago they were villages, surrounded by virgin countryside. It was the Metropolitan Railway which turned them into suburbs, building new lines out to far-flung places like Chesham and Amersham, buying up the surrounding farmland and selling it off to developers.

Back then, between the wars, a brand-new house here in Metroland cost around £250 – about the average annual wage for a clerk commuting into town on the new railway. That £250 bought you a semi with a proper bathroom, an indoor lavatory, a garage and your own garden, front and back.

Compared with the rented inner-city tenements where these first-time buyers had lived before, it was paradise. They raised their children here, and when those children left home they could afford to buy a similar Metroland house nearby. Now one of those Tudorbethan houses will cost you upwards of half a million pounds. In our brave new world of short-term contracts, that’s more like 20 times the annual wage.

And so the current twentysomething generation must move far away to find a proper home, out to Bedford and beyond. People used to grow up and get married and raise a family and grow old here. No longer. A multi-generational community, built up over a century, is beginning to come apart.

Of course, this problem is not unique to Hillingdon. There’s surely hardly anywhere in Britain where you can buy a family house for a year’s salary.

Yet I reckon the sense of disenfranchisement in Hillingdon is particularly acute, because we live fairly near some of the richest places in the country (Richmond, for instance), where house prices are going up and up yet people can still afford to pay.

Most of my neighbours here in Ruislip do regular jobs. They’re builders, electricians, tilers, driving instructors. They don’t do something fancy in the City or the media. If house prices go up they get priced out of the market. They can’t get their children on the property ladder, not like their parents did for them. And that hurts.

At the next election, will this disillusionment filter through into local politics? Unlike most London boroughs, Hillingdon voted Leave, and with Brexit so far failing to deliver on its lavish promises, these Brexiteers have every right to feel disappointed.

My constituency, Ruislip, Northwood and Pinner – unlike most seats in London – is rock-solid Tory, with a 16,000 majority at the last election. Could it turn red this time? A few years ago, to ask such a question would have seemed preposterous. Yet after recent by-elections this fat Conservative majority seems almost within Labour’s reach.

The constituency next door to me, Uxbridge and South Ruislip, hit the headlines last year when Boris Johnson stood down and the Tories defied predictions in the subsequent by-election and clung on (a victory widely attributed to anti-Ulez sentiment, although I reckon the matter-of-fact manner and the no-nonsense credentials of the Conservative candidate had a lot to do with it).

At the time, this improbable result gave Rishi Sunak a glimmer of hope, but it’s now looking like a false dawn, delaying the departure of a PM who sorely lacks the common touch, especially with the sort of folk one finds in Hillingdon.

My wife and I were lucky. We were able to trade in a flat in Chiswick for a house in Ruislip. Most of our neighbours aren’t so fortunate. For the first time in a century, since Metroland was created here in Hillingdon, a local family home is forever out of reach for their children.

If Rightmove had discovered that the unhappiest people in Britain lived in some Labour heartland, Sunak could sleep a lot easier. But these folk are Thatcher’s children. They left the inner city for the suburbs. They left unionised employment and set up their own businesses. They’re the swing voters who decide elections, the C2s, the Mondeo men (and women).

That’s why that Rightmove survey is so revealing. John Major won the 1992 election thanks to the optimism of Essex man. Sunak looks like losing the 2024 election thanks to the pessimism of Hillingdon man.

Unlike Essex man, who loved Thatcher, Hillingdon man has no love for Keir Starmer. But his disappointment with Sunak’s Tories runs so deep that he might just change the habit of a lifetime and give Labour a go.

Listen to William Cook discuss more on The Edition podcast:

Comments