Max Jeffery has narrated this article for you to listen to.

Departing Gatwick train station, with nine minutes till Crawley, I tried to get in the head of a Chagossian. In 2002, Tony Blair gave everyone from the Chagos Islands British citizenship, permitting 10,000 Chagossians to live wherever they liked in the UK. About 3,500 have chosen Crawley. And what a weird thing to do. They took a 6,000-mile Air Mauritius flight to Gatwick airport to start a new life, then settled just a mile from the runway. Why so close?

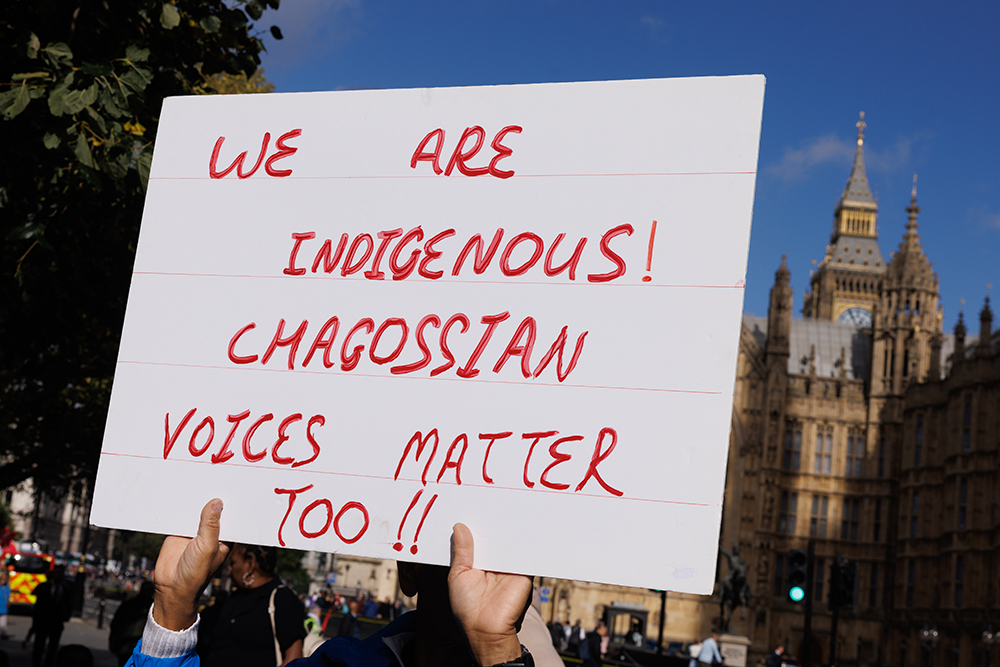

I was visiting Crawley to meet these people I didn’t understand, to find out what they made of our government handing over their islands to Mauritius. On the train I clicked through a few Facebook groups and found a man named Maxwell Evenor who said he was around to talk. Maxwell is part of Chagossian Voices, a campaign group which says it ‘takes the Chagossian voice to the highest levels of decision-making’. I asked him to meet me at a picnic table in Crawley Memorial Gardens.

The Chagossian people were expelled to Mauritius in 1968 by Harold Wilson’s government. The islands were then a British colony, and the US Navy requested to use the largest one, Diego Garcia, as a military base. Wilson wanted to please his American friends, so his government asked the Chagossians to leave. When they wouldn’t, it restricted shipments of food and gassed their pet dogs in sheds. The Chagossians fled, and the Mauritian government was paid £3 million to look after them.

The local Asda stocks Chagossian snacks such as Apollo instant noodles

Maxwell brought his friend Jemmy along to our meeting. ‘I like Crawley,’ Jemmy said. The local Asda stocks Chagossian snacks such as Apollo instant noodles, and there’s a good Chagossian takeaway called Island Kitchen nearby. Jemmy has lived in the town for 21 years but still looked uncomfortable. She kept putting the hood of her coat up and down as if she couldn’t get a grip on the weather. Maxwell has been in Crawley for 14 years. ‘Just got on with it really,’ he said.

Jemmy told me why she left Mauritius: ‘My grandma was adamant. She’s not Mauritian. She’s Chagossian. So is my mum. So is my grandad. So are their brothers and sisters. Chagossians. So you grow up living in the country, but you are not of the country, if that makes sense.

‘I kept learning our history, obviously from my mum, my dad, my grandma, my grandpa. I was told the UK government gave money to the Mauritian government to take care of us, to rehouse us, to rehabilitate us, to allow us to have a decent life. Education and work programmes, all of that. But less than 5 per cent of the population benefited from being removed from our home and thrown into Mauritius. The vast majority of us will tell you this is the reason why we came to the UK. For a better life. If our life was already amazingly great or good in Mauritius, why would we come here?’ Maxwell said that Mauritians were racist to him because he was of black African descent.

I asked Jemmy what she thought of Mauritius being given the Chagos Islands. ‘Yesterday morning we had reporters from the BBC, we had people from human rights groups contact us to say, “Look, you guys, get ready. This deal has happened. It’s been signed off. It’s coming on the news soon. Give your views on this.” Then we get a call at 4 p.m. telling us “We’re really sorry, but it’s a done deal.” And that was by… What’s his name, minister Doughty? Doughty? What’s his name?’

I said I didn’t know, but that Doughty could be correct. (Gov.uk says his name is Stephen Doughty, and he’s the minister of state for Europe, North America and Overseas Territories.) Had Doughty ever spoken to them or any other Chagossians in person? ‘Not in person. Zoom. Everything is done online.’

I said I was sorry, in part because I was, but also because Jemmy was getting angry. She raised her voice until it became so loud that I worried the people of Crawley might intervene in some way. ‘I’m fuming,’ she said. ‘It’s abuse,’ Maxwell added.

It seemed a good idea to pivot the conversation to the Northgate Community Centre. In June, 77 Chagossians arrived at Gatwick without any arrangements for accommodation. They were put in a leisure centre on Crawley’s outskirts, and after two weeks were moved to Northgate, on the other side of town, where they lived on the floor of the village hall. Local papers said the council had booted them out, so I guessed they were now drifting around Crawley’s streets. ‘No. There’s still people in the Northgate Centre,’ Maxwell said. ‘And they’ve been taken to court because the council told them to move. But they don’t have anywhere to go. So they’re going through court proceedings.’

Later I went to the centre: a single-storey building with pebbledash walls and drawn curtains. Two wads of paper were Sellotaped to the glass door. ‘NOTICE TO TERMINATE LICENCE,’ read one dated 26 June. The other was a recent court summons.

The door opened into a plain and dark corridor with a locked disabled loo straight ahead. Someone was in there listening to rap music and making regular hawking and spitting noises. The tap was on too. I sat in the foyer and waited for him to finish.

A different man arrived before the hawking man came out. He wore a tracksuit and had his hair pulled back in a bun. He said his name was Guy, and he lived at the centre. He grinned and two gold teeth glinted. He asked me to wait while he found Kenny, another resident who could speak better English.

Kenny said that of the 77 people who came in June, there were maybe ten left in the centre – those who were under 35 and didn’t have children. He showed me the hall where they were living. It was unclean and filled with rows of camp beds. A sort of screen had been erected to create a second, smaller space, where people could change. Towels were hung over the top of it. Along the walls were cartons of medicine, and people kept their possessions in supermarket bags by their beds.

Kenny handed me a 38-page summary of the case against him and the other lodgers, given to them by the council. The first page invited them to go to the county court on 13 August. Kenny said they’d been, and the magistrate had ruled that bailiffs would come next week. They would bring police to remove the Chagossians from Northgate if necessary. Guy asked to see my identification, because he was worried I was a Mauritian spy. He said he’d seen many of them, and when I asked what he did to spies he stomped his foot on the ground.

At the back of the summary was a letter from Ian Duke, the chief executive of Crawley Borough Council: ‘Many of the group have asked a question regarding where they will go… This is a question that you must answer for yourself. This is why the government advises people travelling from Mauritius to the UK to have first considered how they will be housed. Unfortunately, you have chosen to make the journey without having arranged housing first… We do fully understand the history of the Chagos Islands and the plight of the Chagossian people.’

Finally the hawking man came out of the bathroom, and Guy wanted to show me what he had been doing in there. In the back corner was a blue bucket, the size of a car tyre. They used it to wash, filling it from the tap, rubbing themselves down.

Guy said the council provided them with food and provisions when they arrived in Crawley, but support was cut off once they were ordered to leave Northgate Centre. The town’s smart administrators had learnt lessons from history. They could starve them out. Is that why the Chagossians live so close to the airport?

Watch more like this on SpectatorTV:

Comments