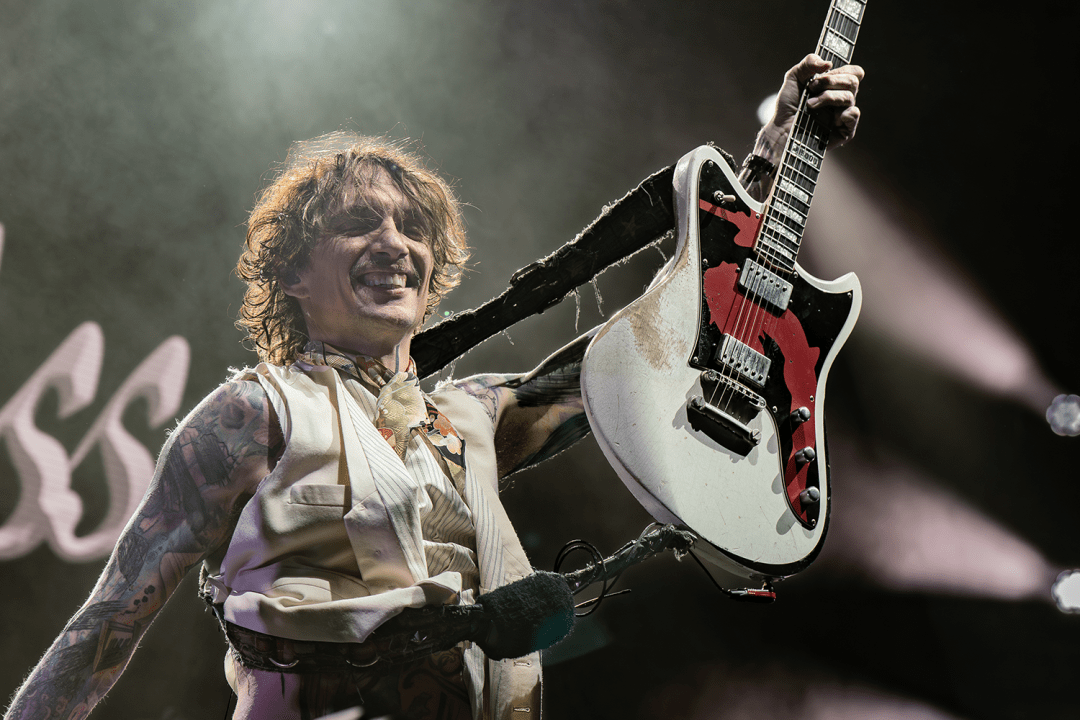

Midway through their thoroughly entertaining show at Wembley Arena, the Darkness played a song from a decade ago called ‘Barbarian’, about Ivar the Boneless and the Viking conquest of Britain. ‘Barbarian’ exists in a long tradition of men with long hair, tight trousers and loud guitars singing about our Danish friends.

Led Zeppelin did it on ‘The Immigrant Song’: ‘The hammer of the gods/ Will drive our ships to new lands/ …Valhalla, I am coming!’ Iron Maiden did it on ‘Invaders’: ‘The smell of death and burning flesh, the battle-weary fight to the end/ The Saxons have been overpowered, victims of the mighty Norsemen.’ Scores of others you are less likely to be familiar with have, too. The Viking anthem is a rite of passage in hard rock.

‘Barbarian’ sounded pretty much exactly as you would expect, with a churning, properly metallic riff, and a characteristically snappy top-line melody from singer Justin Hawkins. ‘One by one, the kingdoms fall,’ Hawkins trilled. ‘They looked upon this isle, and took it all/ Harbingers of pain/ Edmund the Martyr, cut down by a Dane!’ It’s either a microscopically well-observed spoof of metal lyric-writing – so on the nose as to no longer be funny – or it’s just bad writing. That it was performed by the Darkness rather than, say, Manowar was the only thing that stopped it being just another metal song about Vikings.

When they became famous in 2003, the conversation about the Darkness was all about whether they meant it. But of course they meant it. You don’t display such complete mastery of the idiom unless you really love it: the Darkness sounded like a real hard-rock band in a way Spinal Tap never did. But it’s also absolutely plain that the key to their success was Hawkins’s refusal to stay within the bounds of hard rock. The things his bandmates have recorded without him were unremarkable; the things he recorded without them lacked the heft and directness of the Darkness.

Julian Cope once dismissed Van Halen’s magnificent album 1984, because it ‘stepped outside the metaphor’ – in other words, it rejected the world they had created for themselves. The Darkness’s entire purpose was to step outside the metaphor hard rock had imposed – to refuse to re-enact all the metal rituals; to insist on singing the wrong things in the wrong voices. They spoke the kind of metal that people who didn’t know or understand metal could get their heads round. It was a form of code-switching.

More importantly, they cut all the boring bits out. No solos the length of a bank holiday weekend. No bluesy jams. At times it meant that they sounded like several bands within the same song: now Motörhead, now Metallica, vocals reminiscent of Josh Homme from Queens of the Stone Age, an FM-radio friendly chorus, a doomy Black Sabbath chord pattern.

It’s heavy metal for people who like the loud guitars and the velocity but who can’t be bothered with the tribalism and simply want to hear music that reminds them of the bits of hard rock they know they like: AC/DC, Thin Lizzy, Queen. It can’t even really be called metal per se – it’s a very detailed recreation of all the styles of hard rock made between 1978 and 1985 (the band they most closely resemble is the American power-pop band Cheap Trick), but with little doses of Sparks and ELO thrown in (on, for example, ‘The Longest Kiss’).

Which is why a song about Vikings felt so odd. It was the right subject for the genre, but that’s not what the Darkness do.

They spoke the kind of metal that people who didn’t understand metal could get their heads round

Anyway, I was talking to Status Quo’s Francis Rossi about John Cale the other day. Rossi, 75, was thrilled to be told how good Cale, 83, had been at the Festival Hall a few nights before: maybe he could manage another seven years, he pondered.

Other than their age, Cale doesn’t have a lot in common with Quo. I’ve been listening to a fair amount of that spare, arid art rock from the mid-1970s recently – Peter Hammill, especially – that Cale exists within: pop but not pop, exemplified by his still startling deconstruction and demolition of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’, a song turned into an aural scree. There was a rare outing of his 1974 ‘Barracuda’, which I am convinced inspired the arrangement of West Ham United’s 1975 Cup final rendition of ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles’. It was marvellous. And yet the Darkness, the show without brains, was the one that had me thinking for days afterwards.

Comments