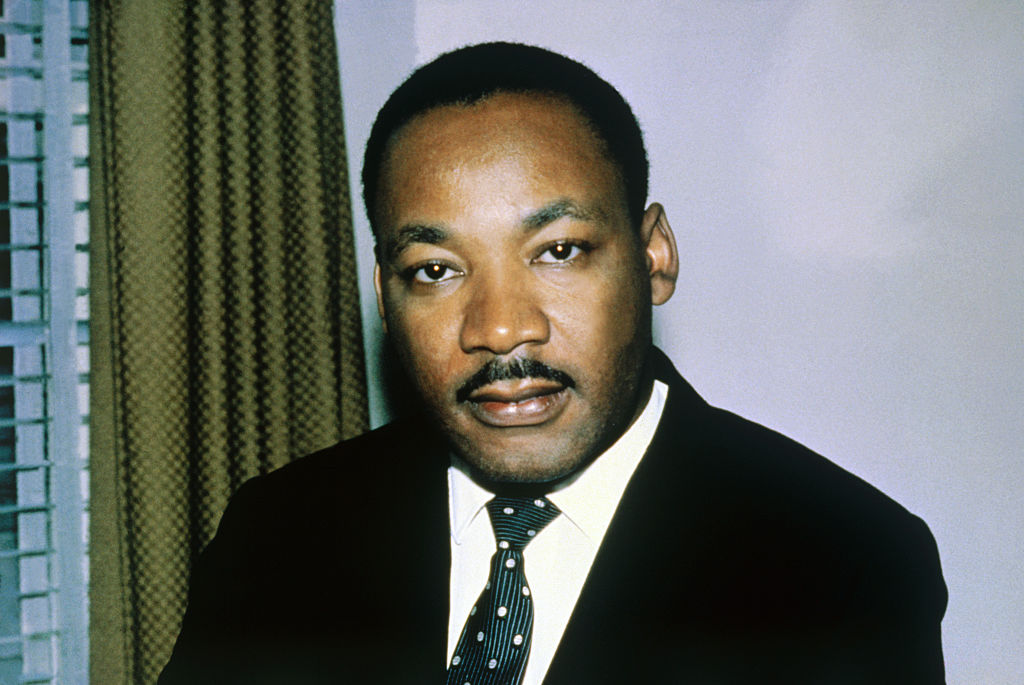

That Martin Luther King was unfaithful to his wife has long been public knowledge. But new revelations from King’s biographer David Garrow in the Times suggest that King’s sexual behaviour towards women is far more compromising than previously thought.

According to Garrow, the FBI bugged King’s Washington hotel room and recorded him boasting about his sexual misdemeanours in a tone that echoes Donald Trump’s so-called ‘locker room banter’. Worse still, Garrow cites a memo that claims King ‘looked on, laughed and offered advice’ as a Baptist minister friend raped one of his female parishioners.

These allegations are obviously deeply serious; they would have made for shocking reading even before the #MeToo movement brought sexual abuse into the public consciousness. And, if true, they should prompt a dramatic reassessment of Martin Luther King. Why then, as Garrow’s editor alleges, did the left-wing press almost universally shun his story on King, in spite of being offered the chance to publish it some weeks ago?

David Garrow is a Pulitzer-prize winning historian. And yet his research into King’s sexual behaviour was allegedly deemed too controversial for the Guardian, the Atlantic and the Washington Post.

It is easy to see why such newspapers passed the Martin Luther King story round like a hot potato: it doesn’t fit into any of the tidy moral boxes they are used to deploying. King’s civil rights cause was crystal clear in its moral direction and still shapes our thinking about racial equality today.

But the allegations place him in the same morally murky category as the Weinsteins of this world: figures who we have ostracised, shamed and censored on the basis of their sexual behaviour. It’s the ultimate moral see-saw: #MeToo or civil rights?

The sad fact of the matter is that, if King had been a hero of the right, then these outlets would have in all likelihood jumped to publish the story. Remember, for instance, the eagerness with which the rumours surrounding former prime minister Edward Heath were reported.

The allegations against King will leave people in a similar moral quandary. I doubt there will be many clamours on Twitter for the removal of the Martin Luther King memorial in Washington DC; there will be no public campaigns to rebrand the hundreds of schools and colleges named after him across the world (there are 77 in the US alone). It’s difficult to imagine students taking to the streets to protest about King’s many cultural footprints in the way that they did for the Rhodes statue in Oxford or the Edward Colston memorial in Bristol.

And nor should they. Martin Luther King’s achievements still stand regardless of his alleged sexual misdemeanours: whether or not he is guilty of abuse, his political actions changed the course of American history for the better.

History is full of morally-flawed characters to whom we are indebted. Rhodes endowed one of the leading educational establishments of the West with money he earned from British colonies; Colston funded hospitals and alms houses in Bristol and yet also traded slaves. If nothing else, the revelations about King are an opportunity for people to realise that, in the round, history cannot be divided into a simple list of heroes and villains.

Knee-jerk censorship, even towards the most shameful aspects of our history, prohibits us from encountering the past as it truly was. In the Black Forest outside Freiberg in Germany, there are several statues of Hitler built to mark the Hitler Youth Movement in the 1930s. These statues haven’t been removed. In fact, a German acquaintance of mine pointed them out to me as we drove past during a recent visit. His willingness to confront his country’s history, however painful, is a trait he shares with most contemporary Germans.

It is right that we hold on to Martin Luther King’s achievements in the midst of these allegations; he is – and always will be – responsible for one of the most important social changes of the last century. But the left should resist the instinct to reconstruct the past in its own image, either by ignoring the revelations or by pointing a censorious finger at other historical figures.

Surely it would be better to accept that humanity is capable of both good and evil, sometimes simultaneously. One only hopes that, in being forced to reassess the private life of such a universally revered leader as Martin Luther King, our culture’s fondness for censoring historical personas who offend its modern sensibilities will slowly begin to wane.

Comments