Four a.m. Something was triggering the motion-sensor on the outside light. One minute, darkness, the next, a window-full of flailing palm leaves, bright with rain. I blinked for a bit, then remembered: hurricane! There was one on its way, we’d been told by Rudy, the beach barman the day before, a bruiser called Ernesto. But Rudy had been phlegmatic: Ernesto is category 1, no problem. iPhone said different. By the light of that terrible little rectangle I fed my fear with headlines from round the world: ‘Ernesto gathers strength and takes aim at Tulum.’ ‘Ernesto careens across the Caribbean towards Mexico.’ ‘Ernesto could devastate Yucatan.’ By morning, I was pale with terror; a victim of my own profession. Rudy explained again: the government will evacuate if Ernesto is a problem. Stop worrying! And yet: ‘Takes aim’; ‘hurtles’; ‘devastating force’. I paced the beach. The sky was black; the sea plain weird, flinging sudden waves right up the sand, ignoring the usual rules of incremental tidal creep. It was enough for me. Avoiding Rudy’s eye, I fled, dragging a reluctant Dom with me. And as we drove, quiet with cowardice, we talked about that distant time before iphones when one took the world as one found it.

I had no idea the jungle at night was so loud. First the relentless football rattle of courting frogs, then great whooping whistles, sudden short screams and the thud of insects the size of mice hitting the mesh-walls of our hut. Only the predators are silent. In the morning, we watched a black tarantula feel his way home, gingerly and confident as a cat.

The road out of Villahermosa to Frontera, where Graham Greene found faith, moved by the humbling piety of ordinary mexicans, is marked for the moment (and the foreseeable) by a dead donkey in what a forensic pathologist would call the second stage of decay. There’s a car dealership, a smart-looking school and the horribly bloated donkey on its back in the fast lane. Nobody seems to mind. The donkey’s off-fore points east across Tabasco’s marshy flatlands, and if you follow the dead donkey, after Frontera you come to Ciudad del Carmen. Back in Greene’s day, Carmen was a fishing village, and the socialist regime was bashing the catholics. Now it’s an oil town and the bashing is done by fat cats — Texans, most of ’em. They call the locals ‘domestics’, bitch about their laziness and hide behind 20ft walls. We passed one oil-money mansion on the way out of town. An automated door whirred back to let out a fancy SUV, and revealed a line of yachts, maybe ten of them in a rack the way another family might have bikes, and a 15ft sculpture of a silver lobster. Someone signing himself ‘Oil man, Houston’ has complained on TripAdvisor that the ‘domestics’ in his Carmen hotel ‘can’t even speak the bloody language’, by which I think he means English.

I read, before I left, an interesting piece about Mexicans in the Guardian. They’re not as Catholic as they’re cracked up to be, said the paper approvingly, in fact the youngsters are rebelling against Mother Church. I looked for signs of a new, secular Mexico as we drove. Quintana Roo, Campeche, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Tabasco: the countryside changes dramatically from state to state, the people too. One thing stays the same — the constant presence of the Virgin Mary, in her Mexican guise as Our Lady of Guadalupe. She was graffiti on the bus stops, she was dangling from the rear-view mirrors of trucks; she was in hotel receptions and gas stations. In San Cristobal de la Casas she was a sticker slapped on the side of wheelie-bins. She was in every single church we visited one way or another — and often in conversation. In England, only loonies talk out loud in church. In Mexico, men and women stop by for a chat with Our Lady of Guadalupe on their way to or from work: to petition, to grumble, to beg or thank; just keeping her updated.

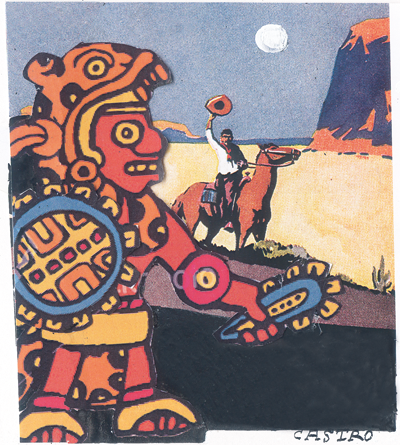

It’s best to switch the iphone off entirely in Mexico City itself, so as to avoid a drip-feed of death: three diplomats shot by police, 35 killed by the Zeta drug cartel, beheadings in the park. In the city’s central square, we traced the violence to its heart: the ruins of the Aztec Templo Mayor, whose sides once ran with human blood. For the Aztecs, human sacrifice was more than an occasional treat. One ruler, Ahuizotl, is said to have sacrificed an average of 1,000 victims a day for 20 days, chopping out their hearts to offer to the god of death. Scholars say the Aztecs had a guilt complex; that without human sacrifice they worried the world would end. I say, they must have enjoyed it or they’d at least have tried goats. Anyway, the whole site is sinking slowly into the lagoon on which the city is built. Soon only the basalt sacrifice stone will be visible, then it too will vanish. It’s difficult to feel sad.

On our plane home, the in-flight magazine was full of adverts for ‘Mayan’ spas. I like the sound of the Mayans — unlike the Aztecs they were into astronomy, maths and only a little human sacrifice — but I wonder how relaxing a Mayan spa would really be. An authentic Mayan spa would have to offer body-piercing, trepanning and the complicated technique they used for making girls cross-eyed, which was considered irresistibly sexy.

Comments