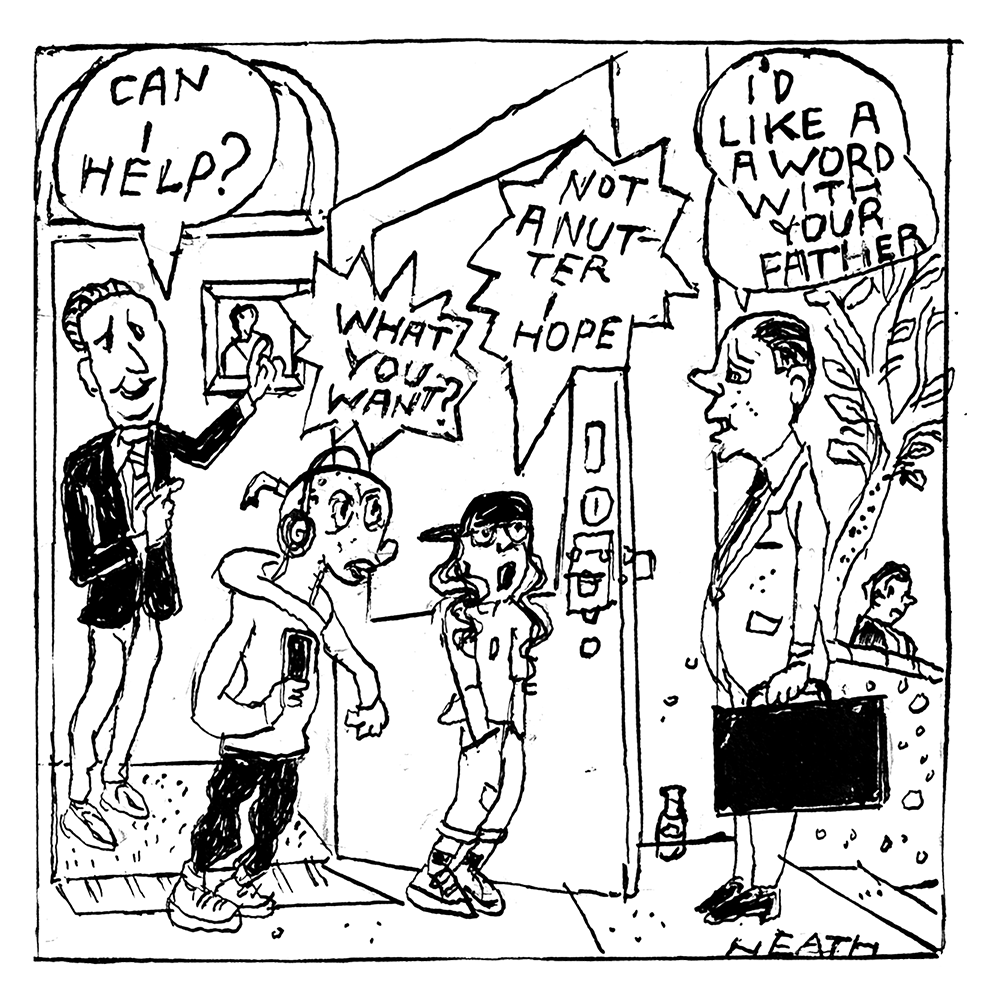

I recently reconnected with an old friend; I went to his house and met his children for the first time. One of them looked up from his screen as we entered the room, faintly curious about the intrusion. The other, with his back to us and his face obscured by a hoodie, didn’t bother. My friend announced their names as if that was sufficient introduction, but it felt weird that the children did not say hello and that one of them did not even show his face. Was something wrong with him? It was a bit creepy. Obviously I let it go. Maybe he was chronically shy or autistic, or facially disfigured. But the brother didn’t behave very differently, so probably not.

It later emerged that Hidden Face did indeed have ‘social-connection issues’ and that his parents were thinking of seeking a diagnosis for autism. By that time, he had deigned to show his face briefly. He shot his mother a venomous glance when she nervously suggested he might sit up for lunch. He whispered some compensatory demand that was instantly granted. I dread to think what it was. I wanted to shake the parents by the shoulders until some sense emerged. Instead, we had a pleasant chitchat about where to go on holiday and what to watch on Netflix.

It chilled me, the glance he shot his mother. It should have earned him a stern rebuke. But it seemed that he was holding an invisible Kalashnikov. His parents feared him. It chilled me but didn’t massively surprise me. Depressingly, I have seen many such cases.

Most readers will agree with the next sentence strongly, but will seldom have seen its sentiment in print. We are suffering an epidemic of disastrously bad middle-class parenting. Dramatically spoiled children are no longer a Roald Dahl rarity but are semi-normal, and many parents dodge blame through the procurement of a diagnosis of this or that condition.

I am writing anonymously. It’s pretty obvious why. If my name appeared on this article, I would lose a few friends and a few family bonds would be broken. Obviously some chatty journalism refers to the problem and a few sober opinion pieces appear. But in general journalists have failed to provide a space for reflection on this issue, despite its importance. And of course the reason is exactly the one I have given for my anonymity: journalists have siblings and old friends that they don’t want to lose. Speaking truth to power is one thing; speaking it to one’s sister is another.

There’s another factor. Why offend people who do their very best to raise children with behavioural difficulties of any kind? Why lump them in with bad parents, scared of the little monsters they have made? Why add insult to their injury?

But the issue has to be addressed. We shouldn’t pretend that bad parenting doesn’t exist, just because there is a risk of offending good parents of difficult children. And we should admit that bad parenting can actually create children with pathologies.

To be clear, I am not arguing that most children diagnosed with a behavioural condition are really just spoiled. I know some families with autistic children who have worked hard to socialise them, to ensure that they greet family friends when they come round, and so on. But I also know families where the source of the problem is clear as day: the parents have drifted into the terrible habit of failing to teach their children how to behave.

It seemed that the child was holding an invisible Kalashnikov. His parents feared him

I nearly wrote ‘of failing to discipline their children’. Maybe that word is best avoided, as it suggests six of the best and so on. But discipline really just means teaching, or maybe ‘deep-teaching’. And a child must be taught how to behave around other people – how to keep quiet about his or her desires, how to behave in a vaguely formal way, even at home if people come round. Even this might sound a bit harsh and Victorian to some. ‘We don’t want him to conform and be polite, we want him to be himself,’ a parent might say. But this is a subtle cruelty, because it will lead him to be disliked.

It seems that some parents, for psychological reasons we do not need to ponder here, do not really want their children to be liked by people outside the family – even by aunties and grannies. Maybe it makes them feel they have a closer bond with their children. Maybe they half-want to alienate the bossy granny. They dare her to criticise the child’s behaviour and cut herself off from contact. This is to weaponise one’s child.

And it seems that some parents feel that their child is too special to be disciplined. Sometimes this stems from fertility issues – to risk insulting another sector of parents (I’m liking this anonymity thing). His or her birth was such a struggle and such a miracle that the normal rules are out of the window and only pure affirmation will be given. No old-fashioned coldness in this lucky home! But what is the child going to do? Dump its parents for being a bit too Victorian and seek new ones, aged one?

I am not going to conclude with a lecture about old-fashioned parenting. But one tip springs to mind. Parenting involves a bit of acting, performing, role-playing. When parents set boundaries and act a bit tough, their love is not diminished. But they half-hide it, they half-threaten to withdraw it. This is a benign act. Through it the parents represent the outside world, with its rules and power to hurt, and make it less scary. They bring a bit of the harsh world into the home, out of long-term love. Their role is not just to love their child, but to teach her rules and habits that make her more widely lovable.

Comments