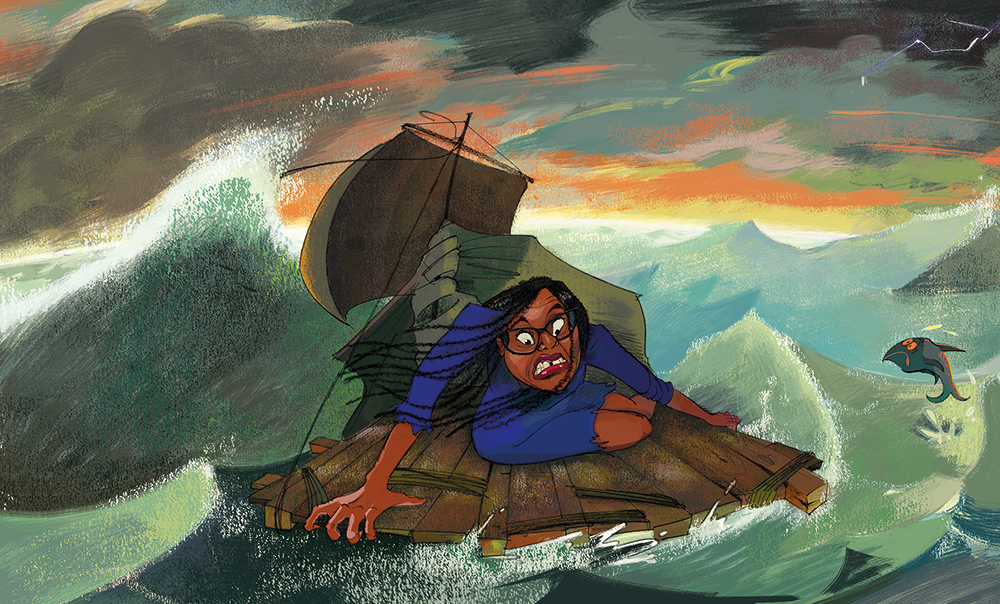

For me, it was the sideboard that did it. Originally the centrepiece of my grandmother’s dining room, upon her death it was passed on to my mother, who kept it grudgingly in her cottage even though you couldn’t get to the kitchen without banging your hip against its bow front. At some stage it was passed on to my sister, who paid a considerable sum to store it because she had no room for it in her terraced house. Some years later, I was informed that I must house this precious mahogany albatross myself. After some handwringing and sadness, lack of space forced me to pass it on to someone in my village. She took one look and promptly vowed to ‘do an upcycle’.

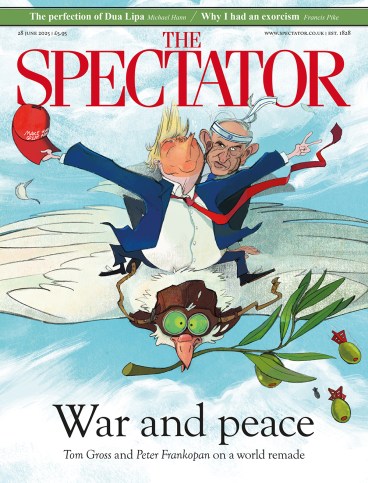

Some boomers are resigned to the fact that the sale of brown furniture isn’t going to ‘fund any skiing holidays’

Such is the sorry fate of brown furniture. It is unwanted by millennials, who will likely inherit it anyway when their boomer parents inevitably downsize, to allow their offspring to scramble on to a much lower rung on the property ladder. Brown furniture strikes me as a peculiarly apt metaphor for the cumbersome, unwieldy process of the Great Wealth Transfer more broadly.

It may sound like a heist, but the Great Wealth Transfer is the anticipated handing down of approximately £5.5 trillion from the boomers to millennials, what journalists and financial analysts like to call (with no apparent irony) the ‘largest flow of generational capital ever seen in the history of humanity’. Maybe we should simply call it The Generation Game and get Bruce Forsyth back from the grave to officiate. Because like all game shows, there will be winners and losers. Just don’t expect a conveyer belt and a teddy bear.

But first, a word for the boomers. Britain’s baby boomers – the 13.5 million people, aged between about 60 and 80, who were born between 1946 and 1964 – grew up in a world of staggering growth. As they worked, they were able to pay into pensions and buy shares. Overwhelmingly, they bought houses, and these houses have become a lot more valuable: a flat bought in Notting ‘Grotting’ Hill in the 1970s for £6,000 is now worth well over £1 million. Half have more than £500,000 in assets and roughly a quarter have more than £1 million. This has helped make the boomers comfortably the richest generation there has ever been – and quite possibly the most reviled. As a geriatric millennial born in 1983, waiting for the wealth to trickle down into my hands, I can’t wait.

Except I don’t seem to be in line for any wealth as such, but a whole auctioneer’s catalogue of brown furniture given to me as property has changed hands from my grandmother’s so-called silent generation to my boomer mother, who now doesn’t want it (and has even been known to Farrow & Ball it). If I do inherit any property, it probably won’t be until I am well into my sixties, when my children have completed their (hopefully) private education. As I really don’t want my mother to croak it any time soon, I am at peace with this situation.

Through no meritocratic slaving of my own, I have managed to get on to the property ladder via my husband. The Bank of Mum and Dad regrettably never opened its ATM for me, as it did for so many of my peers, but hey-ho. What has trickled down to me thus far in the greatest asset swap of all time can be listed as follows: a Davenport desk, a couple of Pembroke tables, a side cabinet, a linen press, two gilt mirrors, a wig stand and a great deal of bone china, designed for the kind of entertaining that hasn’t taken place since the 1940s.

Brown furniture, then, is my lot. But brown furniture, as auctioneers are at pains to tell me, is worth nothing – it is the abject symbol of generational misalignment that will come to characterise the slow death march of the boomers and expose the Great Wealth Transfer once and for all. Blame Tony Blair – ‘forward not back’.

But why? Shouldn’t it be worth something? I spoke to Thomas Jenner-Fust, director of Chorley’s in the Cotswolds, to confirm just how shafted I am. Jenner-Fust blames ‘generational dissonance’ for having driven the value of brown furniture down: ‘Boomers came from a world where people still sat around a table to eat food, took afternoon tea (no ghastly mugs), sat at a desk to write letters with an actual pen and displayed their trinkets and treasures in display cabinets.’ In contrast, he says, millennials lead different lives in knocked-through kitchens where mahogany furniture looks out of place, and built-in cabinets throughout the house have done away with the need for hulking great bow-fronted chests of drawers. And of course many millennials don’t have a home at all to fill with brown furniture, even if they wanted to.

Some boomers, I quickly learn, are resigned to the fact that the sale of brown furniture isn’t going to ‘fund any skiing holidays’; ‘luckily for them, over the same period [35 years] their Old Rectories have gone up by millions so they can take a hit on the Pembroke tables’.

Others, upon discovering that their corner cupboard is worth only £30, are not so sanguine. ‘I have often felt that I am about to be chased out of the house with a rolling pin. I’m seen as a sort of swindler,’ confesses Jenner-Fust, letting slip that when an auctioneer acquaintance sells a piece of brown furniture for a pittance, he often remarks ‘at that price I hope the legs fall off’. Which of course, unlike their Ikea counterparts, they won’t. Brown furniture, like a boomer’s incredible life expectancy, is sturdy and built to last.

Eliza Filby, historian of generations and author of Inheritocracy,published last year, sees the glut of brown furniture as evidence of the fact that ‘boomers are the consumer generation that have bought a lot of shit’. By contrast, millennials and Gen Z are the experience generations, all holidays and Instagrammable ‘memory-making’.

Brown furniture, Filby says, is a motif not just for different ways of living but, crucially, for different economic standards of living, standards that were far more elevated than we victimised millennials could dare to imagine. ‘There’s a reason why millennials embraced the pared-down mid-century aesthetic,’ she notes. It is born out of economic and social dire straits rather than simply solipsism. Minimalism arose then because there was simply less space: no dining rooms, less wall space for gilt mirrors and linen presses – just less.

What, then, is the answer to this generation game of discontent? James Mabey, partner at law firm Winckworth Sherwood, tells me that, as with most things, tech may be the answer. Technology that can predict life expectancy may be ‘a very powerful tool in estate planning in choosing how much to give away and when, and how much we are each likely to need to keep back’.

The short-term risk, though, is that millennial inheritance gets drunk through a straw by boomers on their so-called ‘revenge holidays’. I conclude, in the words of the late, great Bruce Forsyth, that I must ‘play my cards right’. Just no more sideboards, please: I flogged the dinner service ages ago.

Comments