Alongside his distinguished career as a painter, Howard Hodgkin has also long been a collector of note. As a schoolboy at Eton he was given to bouts of running away but while briefly in situ his art master, Wilfrid Blunt (the brother of Anthony), borrowed a 17th-century Indian painting of a chameleon from the Royal Collection to enliven a lesson and Hodgkin was hooked. He started buying Indian pictures then and has continued ever since.

‘My collection has nothing to do with art history,’ he says. ‘It is entirely to do with the arbitrary inclinations of one person.’ It is a method that has, nevertheless, resulted in one of the world’s great collections of Indian art. Hodgkin has made several attempts to stop buying more but he’s a recidivist, not least because ‘a professional artist sells what he makes. Buying art fills the void that comes as each work leaves the studio.’

The fruit of his compulsion, 115 pictures that alternately dazzle and mystify, is now on show in Visions of Mughal India at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. It doesn’t quite amount to an overview of Indian painting from the mid-16th century to the mid-19th because some genres, notably religious images, don’t much interest Hodgkin. The exhibition does, however, give a vivid account of the different Indian schools and the sometimes extraordinary quality of its usually anonymous artists.

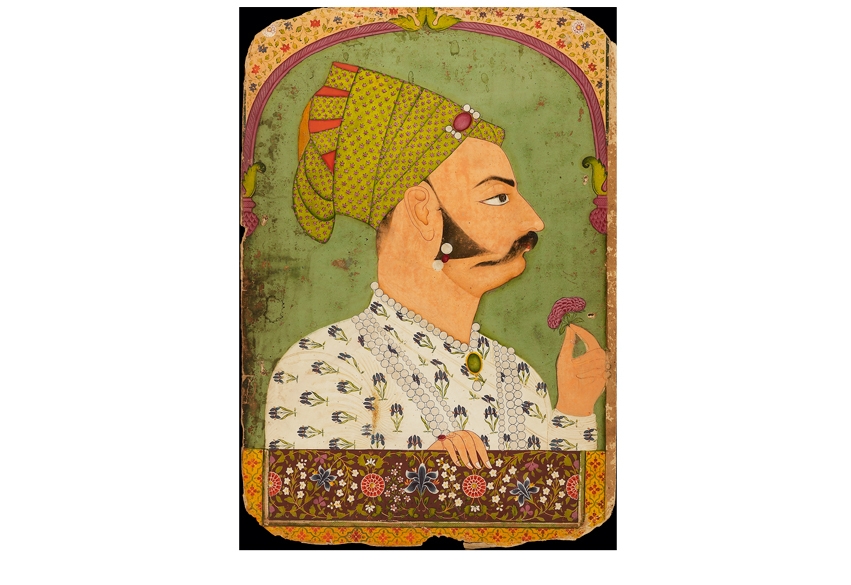

The Mughal school of painting was founded by the Emperor Akbar (reigned 1556–1605), the grandson of the dynastic head Babur. He encouraged a court art that married Persian miniaturist techniques with local Indian manners and European influence. The style spread — and was adapted — across India, from the Punjab to the Deccan Sultanates. The repertoire of subjects encompassed court life, portraiture, wildlife and hunting scenes, all depicted with a love of pattern and with pale green as a signature colour. The majority of the works were for manuscripts and that is perhaps how they are best viewed, not in comparison with Western oil painting but with the medieval illuminated manuscript tradition. This makes more sense of their lack of perspective, the importance of profile, the mixture of sizes within a single image, and the non-naturalistic use of colour that seem so alien to eyes accustomed to European Renaissance paintings.

It is, though, almost impossible not to make references to Western art when looking at Hodgkin’s collection. There is, for example, a beautiful portrait drawing c.1640 of Iltifat Khan, a minor official in the court of Shah Jahan (the builder of the Taj Mahal), that is Holbeinesque in its immediacy and spareness. In life, Khan was apparently a well-born underachiever, but the artist shows him in pure profile, bright-eyed and alert; he could have been a member of Henry VIII’s circle from a century earlier and a world away — courts and courtiers are interchangeable.

Scenes of noble life — a music party by a river or the delights of a cup of wine and a hookah pipe on a terrace — are rendered with a minute detail that recalls the paintings of the sharp-edged documenter of Venetian life Vittore Carpaccio. Hunting scenes with tigers the prey are as common in Mughal art as paintings of bear or stag hunts are in the West. As are rich men’s toys. Akbar’s pigeon coop held some 20,000 birds, the pick of which he liked to watch fly in synchronised ‘love play’. He had a favourite male and female pair depicted in a touching image of avian devotion; they nestle against each other with the imperial gold rings on their legs, each blue-grey wing feather rendered in exquisite detail against the pure white of their bodies.

The most prized possessions, though, were elephants and they are Hodgkin’s favourites, too; the exhibition is filled with the trumpety trump of pachyderms. There are portraits of individual animals, proudly displayed just as Georgian aristocrats would ask George Stubbs to immortalise their prize horses, and a vivid scene of the capture of a wild bull elephant, each stage of the dangerous procedure shown in bande dessinée style. The most thrilling example is a wondrous drawing of two elephants fighting, c.1655–60, from Kota in Rajasthan. In a tour de force of penmanship the animals clash heads, coming together in a Celtic knot of trunks and legs, the fluid rippling of their skin brought out with a maze of Op Art hatching. It is a picture of enormous skill and these remarkable beasts are the Indian equivalent of Dürer’s rhinoceros.

This dazzling little exhibition, a compilation of Indian Scheherazade tales, is full of such surprises. Hodgkin says that when buying, what he looks for are pictures that give ‘an authentic shot to the heart’: there are more than enough examples here to deliver the most pleasurable of palpitations.

Comments