Last week a man called Peter Fitzek was apprehended by police. He calls himself King Peter I, and he is the head of the ‘Kingdom of Germany’, the largest of a number of groups that don’t accept the legitimacy of the current German state and want to replace it with their own. Monarchism may not be widespread in Germany, but the idea certainly has a dedicated following.

Police came down hard on Fitzek’s realm in coordinated morning raids last Tuesday. Over 800 police officers stormed and searched properties in seven German states, leading to the arrest of ‘King Peter’ and three other people deemed to be the ringleaders of the group, which is estimated to be 1,000 members strong (though Fitzek claims it’s 6,000 nationally).

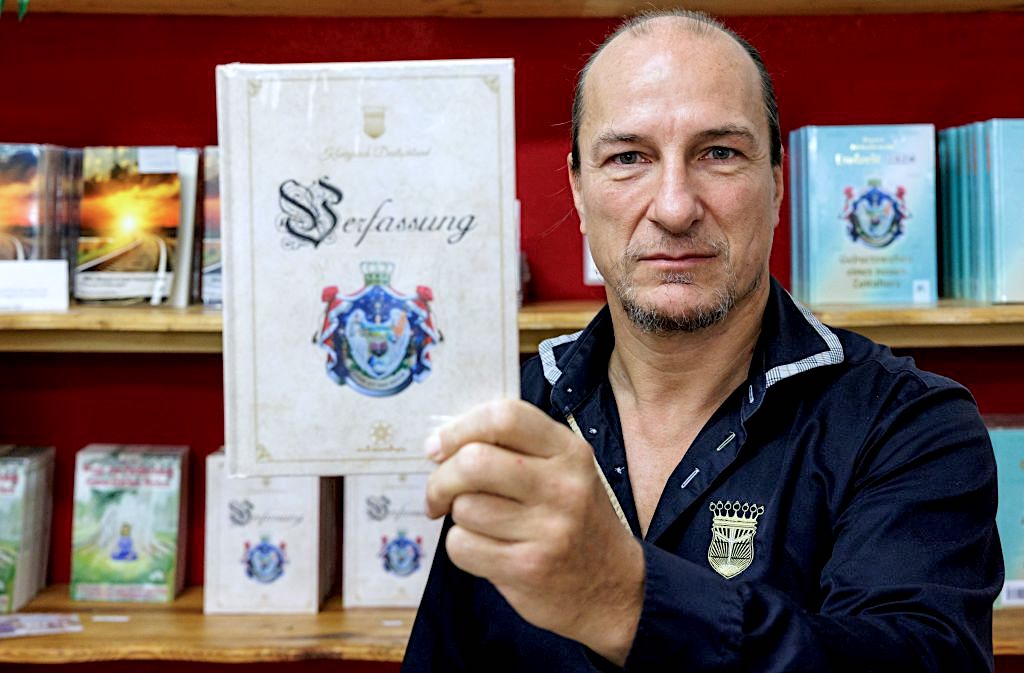

What Fitzek offered his followers was to join his parallel state, a fantasy kingdom he called ‘Konigreich Deutschland’ (KRD). A trained chef and karate instructor, to his ‘subjects’ he was ‘King Peter I’ or ‘Peter, Son of Man’. The 59-year-old, who wears what’s left of his hair in a ponytail, appears to have had a ‘Guru-like’ appeal, able to captivate people, as one ex-member told the German newspaper Die Welt.

In KRD recruitment seminars, the leaders described the current German state as corrupt and illegitimate. Money was flowing from ‘hardworking to wealthy’ people, the ‘elites’ stopped people from developing their ‘creativity’, and the banking system had been invented by the Rothschilds to trap people in high debts. Fitzek promised them a better world, a ‘state for the greater good.’

Through the money of its members, the group has been able to buy an extensive portfolio of properties, including former hotels, manor houses and country holdings. There, they claimed to set up their own state with its own economy, into which members were supposed to invest. This included their own health insurance (‘Deutschen Heilfursorge’ or ‘German Medical Care’) and banking system (‘Konigliche Reichsbank’ or ‘Royal Reich Bank’). Members swapped their euros to the KRD’s own ‘Engelmark’ or ‘Angels’ Mark’. When police raided the organisation’s properties in November 2023, they found €360,000 worth of cash and bullion.

Fitzek’s realm also claims to run an independent administration that sits outside of German law. Members receive new identity papers such as passports, issued by the ‘Kingdom of Germany’ complete with its own emblem, a rising sun with a crown on top. When the organisation was first set up in 2012 by Fitzek and eight fellow travellers in a sports hall, the ‘king’ was invested with the traditional coronation insignia of a sceptre and orb as he shrugged on his royal mantle.

One could argue this is all harmless role-play, a fantasy world inhabited by lost souls disaffected with reality. But that’s not how the German state sees it. Domestic intelligence has been monitoring Fitzek’s activities for years. He’d previously received a prison sentence of several months. Now, in one of its very first moves, the new German government cracked down on the DRK.

Upon taking office, the new interior minister, Alexander Dobrindt, immediately banned the organisation, declaring that ‘the purpose and activities of the association run contrary to the law and are opposed to the constitutional order.’ His ministry argued that the ban demolished the ‘largest association’ of a ‘scene that has been growing for years’, that of ‘the so-called Reichsburger and Self Administrators.’

The Reichsburger scene is disjointed and comparatively small

While Fitzek’s kingdom seems cultish, set up as an escapist enterprise that promises newcomers their ‘first steps out of the system’, other Reichsburger (‘Reich Citizens’) groups have explicitly called for a violent overthrow of the state. In March, a court jailed five members of one such group for plotting an armed coup that would have involved the kidnapping of the federal health minister.

In what they called Operation ‘Silent Night’, they planned to attack the power grid, causing blackouts and thereby creating civil-war-like conditions. Then, members of the military and police, allegedly as fed up with the state as the conspirators were, would join them, replacing the illegitimate system with a monarchy headed by minor aristocrat Heinrich XIII Prince Reuss. The defendants received between five years and nine months and eight years in prison.

What sounds – and is – a far-fetched plan would be easy to laugh off, but police did find significant funds and hundreds of weapons, including illegal firearms – in their raids. The Reichsburger scene is better connected than it was, counting former MPs, judges, members of the armed forces and police officers among their supporters. Most importantly, as Fitzek’s case shows, they have access to significant funds through their members.

It is also true, however, that the Reichsburger scene is disjointed and comparatively small. Domestic intelligence believes there are around 25,000 supporters, of whom it estimated 2,500 to be of a violent disposition. In 2023, 149 incidents of violent crime were attributed to Reichsburgers.

The groups have different aims. Some regard Georg Friedrich, Prince of Prussia, the great-great-grandson of the last German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, as the legitimate ruler of Germany. They believe the forced abdication of the House of Hohenzollern, which Georg Friedrich heads today, was illegitimate after world war one. Ergo, the German Empire or Second Reich still exists to them – hence the name ‘Reich Citizens’. Others, like Peter Fitzek or the group around Heinrich XIII Prince Reuss find new rulers for their self-declared states.

What the Reichsburgers groups have in common is that they don’t see the current German state as real or legitimate. Many do what Fitzek did: create their own currencies, passports, and legal structures. Some of the groups are also linked to others internationally or take inspiration from them. The American QAnon movement and conspiracy theory has a sizeable following in Germany, for instance. In light of growing public disaffection with mainstream politics, German authorities are wary of groups that appear to erode trust in state institutions.

The big question is whether big public crackdowns like the one this week help or hinder the rebuilding of trust in state authority. While most Germans are unlikely to have much sympathy for people they regard as fantasists, those who are already sceptical of government intervention and force might see this as confirmation of their fears. The new government must tread carefully in finding a path between safeguarding public security without overreacting.

Comments