At first I thought this was going to be a terrible book. It starts like a Hollywood B-movie Western on which Ingmar Bergman has done a quick rewrite. This, for example, is how the authors convey the simple fact that Oliver Cromwell died on 3 September 1658: ‘Death finally caught up with Oliver Cromwell on a muggy summer afternoon in 1658.’ All it needs is the dusty main street of the frontier town with two men, one all in black, facing each other against the sky, with one of Dmitri Tiomkin’s lush orchestral soundtracks gulping away in the background.

Another death — that of Charles I by execution on 29 January 1649 in Whitehall: carpenters are putting the finishing touches to his scaffold and, according to the authors, the sound awakens the King. Fair enough. Carpenters hammer, they saw: many of us have been woken by carpenters. But then Messrs Jordan and Walsh go further.

Sitting up, he pulled back the heavy curtains surrounding his bed. Cold air rushed around his face. By the light of the large candle left burning through the night he read the dial of the little silver clock hanging on the bedpost. It was just after five o’clock in the morning.

All right, this is what a waking man would do. It is just that we do not know if this is what Charles did, for no source is quoted. Cold air, yes; consulting a clock, yes, a man would have done this, especially one on the morning of his execution. It is just that to introduce such specific detail in the interest of colour brings with it the steady drip of suspicion that fact has become probability, and this is fatal for it throws a historical work off balance.

Again, the muggy afternoon of Cromwell’s death. How do they know it was muggy? Only because a well-attested storm followed, so the weather must have been heavy in the countdown to it. The irony is that none of this is necessary.

What follows on the over-coloured description is already the most colourful, most dramatic sequence of events in all English history. It is an account, balanced for the most part, of what happened to the 67 judges who were present on the last day of his trial and heard the sentence of death passed on Charles I.

Who were they? They were the most respectable and formidable rebels ever assembled, for it was the ruling class of his country that sat in judgment on their King, that and the remarkable men who only emerge in remarkable times. Most were soldiers, three generals and 34 colonels, who had abandoned civilian life to serve in the invincible army which had defeated him when he declared war on his own people and their parliament. Some were grandees, three peers, 22 baronets and knights, and four aldermen of the City of London.

And what happened to them, when the King’s son Charles II, to his own great surprise, came into his own again 12 years later, and managed to take his much delayed revenge? The execution of his father had been a terrible affair. What followed was a shabby, and thus far more terrible, affair.

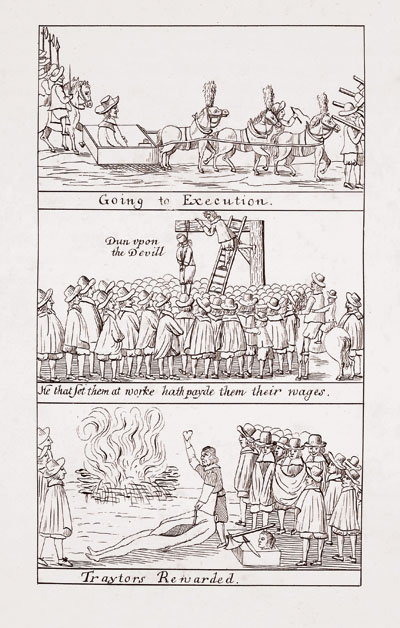

The long dead, like Cromwell and Ireton, he had dug up and their rotting bodies hanged. Some he had tried, though without defence counsel. He and his kangaroo courts had six of his father’s judges, and four others (including his prosecuting counsel) hanged, drawn and quartered, that is to say half-hanged and their still living bodies castrated, their bowels torn out, their limbs hacked like the pigs’ carcasses you see hanging in butchers’ shops. This stopped only when it became a PR disaster, for the victims went to their terrible deaths with such dignity that a further 19 had to be sentenced to life imprisonment, which in their case did mean life imprisonment. Some historians have managed to write about his clemency, but these authors have little time for the Merry Monarch.

For after all this he still was not done, and had his murder gangs, one led by Sir George Downing of Downing Street fame, scour the Continent and North America for those 15 who had managed to make their escape. Many surrendered, trusting to the King’s mercy, others managed to cut the sort of financial deal at which the Stuart kings were so adept; regicides actually sat in Charles II’s parliaments.

This would make a wonderful film. The cast is already assembled, amongst them Fairfax, the supreme commander of the army and, as such, the one man who could have stopped an execution to which he was opposed, but didn’t; the stiff, duplicitous little King; the overwhelming Cromwell; Henry Marten who alone made them laugh and thus provides a rare humanity, most of the others being on such a scale they could pass for demi-gods.

One of these, General Harrison, being taunted on his way to the gallows, was asked, where was his Good Old Cause now? He replied, ‘Here in my bosom, and I shall seal it with my blood.’ Another, Colonel Gough, hid in a Connecticut cave from which he emerged in extreme old age to lead the settlers to victory over attacking Red Indians.

Only one thing would pose difficulties in the casting. The returning Royalists and the turncoats who triumphed with them were a grubby lot; it would be impossible to accept them as the good guys. Still this is a terrific read.

Comments