A question for those of you of a certain age. Who was the first articulate black person you ever saw or heard? My guess is that it would be Muhammad Ali or, if you are a little older, Cassius Clay. Obviously if you yourself are black the question should be a little different. Then it would be who was the first articulate black person you saw on TV?

Of course there were plenty of black people in the world before Clay came along, loads of them. Back in the 1960s they impinged on the rest of us largely as entertainers, if they were famous black people, or as the unwitting cause of indigenous race riots if they were not. But they did not really speak to us; we knew nothing of them, here in England. No matter how much we appreciated Fats Domino and his rather literal manqué, Chubby Checker, the entertainers were somehow aloof from the fray: one was accustomed to negroes singing things, they had a certain talent for it, we believed. But their concerns, their aspirations, were a mystery to us. Until Cassius Clay came along.

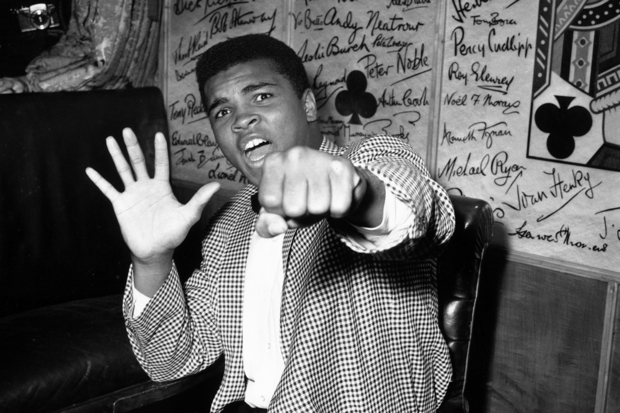

I do not want to overstate Clay, or Ali’s, articulacy. There was a mildly witty braggadocio about him, a winning and sometimes prolix self-confidence, and that was about it. He was not, as some might paint him, a sort of pugilistic George Bernard Shaw. And there was an undeniable awkwardness about his television appearances – both ringside and, famously, with Michael Parkinson – the vague suspicion that we were in the presence of a performing seal: a sportsman, a black sportsman, a working-class black sportsman, who could talk!

And yet that self-confidence – born, one supposes, of the knowledge that he could beat the shit out of anyone who crossed him – was itself revolutionary. We had not seen that kind of thing before, and it came as a shock. Suddenly we were confronted by the fact that negroes – which is what we called them, back then – were not entirely happy with their lot in the United States. We had gathered – from the televised reports of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X – that there was disquiet over there, and the older British population might remember the way in which black US servicemen were horribly discriminated against by their white compatriots during World War Two. But it took Clay, or more properly Ali, to articulate those grievances and more besides.

The Vietnam War, for example. Many British people were unconvinced by the USA’s brutal and ineffective intervention and so we did not howl with righteous outrage – as did white America – when Ali steadfastly refused to fight, insisting that he had nothing against the Vietnamese and that this was a white man’s war. Well, yes, many of us reckoned, you’re probably right about that. And so, for a while, Muhammad Ali was rather more adored in the UK and Europe than he was at home, where the race fires were still burning.

I don’t know anything about his abilities as a boxer. I assume he was at least fairly good. Boxing is as much a mystery to me as quantum mechanics and the baleful progress of degenerative illnesses. I watched a fight of his once on TV, in the 1970s, against a man called, I think, Joe. Ali seemed very adept at punching Joe in the face. A nasty trade, boxing. Noble my arse.

Just occasionally it happens that by chance someone actually changes the world we live in, perhaps without meaning to. Maybe as the consequence of their ability in one or another sphere – or just a simple twist of fate. I think Muhammad Ali did that.

Comments