The thing about Islamists is that they just can’t help themselves. Mohammed Mursi’s stock was riding high in certain quarters shortly after he slapped down Hamas in Gaza and avoided a full-scale confrontation with Israel. Foreign policy panjandrums in London and Washington who tout fashionable theories of a ‘moderate Muslim Brotherhood’ felt vindicated in their convictions, arguing the group is really just an Arab version of European Christian Democrats.

Yet so attracted is the Brotherhood to the clarion call of reaction that after the ceasefire, Mursi instantly seized the moment to reveal his proclivity for authoritarianism. There is now no authority in Egypt that can revoke the president’s decisions while he is also empowered to do whatever is needed to ‘preserve the revolution and safeguard national security’. These terms will be widely constructed, leading many Egyptians to regard them as opening the door to a new dictatorship.

Mubarak employed similar ambiguities to consolidate his control, ruling Egypt with an Emergency Law after the assassination of Anwar Sadat. Much like Mursi is arguing now, Mubarak insisted the decree was necessary for the preservation of civil order and national sovereignty.

Mursi’s actions in recent weeks can seem contradictory. Yes, he avoided agitating for greater conflict with Israel but this was likely motivated by the instincts of self-preservation rather than temperate statesmanship. After all, the Brotherhood waited almost a century to realise power – and now it rules one of the Muslim world’s most important countries.

Eric Trager, a Fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, notes:

Mursi’s political biography suggests that he is not a compromiser. Prior to last year’s uprising and his subsequent emergence as Egypt’s first civilian president, Mursi was the Muslim Brotherhood’s chief internal enforcer within the Guidance Office, steering the organisation in a more hardline direction ideologically while purging the Brotherhood of individuals who disagreed with his approach.

This history explains the dexterity Mursi has shown since becoming president. After freeing himself of all judicial oversight he ordered the Islamist-run constituent assembly to submit its draft constitution immediately. Secularists have long since boycotted the process and were challenging the assembly’s legitimacy in the courts before Mursi disenfranchised them with his new powers. When the courts threatened to issue a ruling anyway – thereby directly challenging the president – his supporters blockaded the Supreme Court, making it impossible for judges to meet there.

There is much to worry Egyptians in the new constitution. Explicit provisions guaranteeing women ‘equal status with men in the fields of political, social, cultural and economic life’ have been removed. A ban on ‘insulting prophets and messengers’ has also been proposed, alongside recommendations that the Islamic university of al-Azhar ‘should be consulted in all matters related to Sharia.’

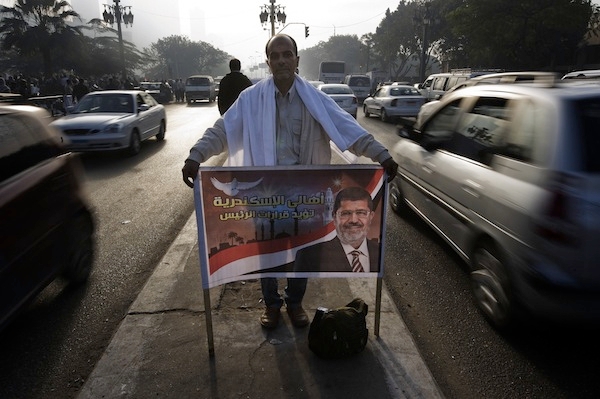

Unrest over the last week demonstrates the extent to which many Egyptians are deeply uneasy with Mursi’s posturing. He has effectively divided the country in two: with Islamists on one side and secularists on the other. Should the latter lose, Cairo will be well on its way to becoming the Caliphate.

Comments