It was Sir Hubert Parry who in 1899 complained about ‘an enemy at the doors of [real] music… namely the common popular songs of the day’, ten years before he put a William Blake poem to music and came up with the most famous classical/pop fusion of all time, ‘Jerusalem’, which even featured on a mid-1970s number-one album by ELP.

I did assume that a book subtitled How 20th-Century Classical Music Shaped Pop would reference such synergies. It does not. Elizabeth Alker’s is instead a competently written, entertaining if scattershot history of avant-garde electronic music, but presented as if some musical chasm separates John Cage from Sonic Youth. In fact one can easily draw a line between the two. Just follow the yellow brick road: the two Johns (Cage and Cale); the Velvet Underground (a chapter); Suicide (no mention); early Pere Ubu (no mention); ‘No Wave’ (no mention of ex-Ubu member forming No Wave trio DNA); Sonic Youth.

Instead, by referencing chart acts such as Donna Summer and Radiohead – beginning chapters ‘about’ these acts that quickly veer off-piste – Alker aims to establish connections I’m not sure are there. Radiohead name-dropping musique concrète in interviews demonstrates no greater link than when David Bowie told Alan Yentob he was influenced by William Burroughs’s cut-up technique before trying to demonstrate the same – and failing.

The chapter on Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’ eventually arrives at the classical innovator Karlheinz Stockhausen via three degrees of separation: her producer Giorgio Moroder to Can’s Irmin Schmidt to Stockhausen, a tad tangential, justified by suggesting they were all part of a ‘typically German’ attempt to ‘jump-start a progressive kind of European pop’.

Er, note from teacher: see me after class. ‘I Feel Love’ came along ten years after the birth of prog, the single most commercially successful form of album-length pop since the invention of sound, containing more classical/pop crossovers than any other popular form. The entire synth-driven genre – and yes, I mean bands like Yes – gets zero mention. Not even Roxy Music!

Parliament, on the other hand, gets a chapter, alongside Lydia Lunch, the Blessed Madonna (no, not that one) and Nils Frahm. All interesting folk, each pushing at the parameters of song. Combined sales? Less than Brain Salad Surgery (see above). A lot less. Perhaps I’m doing Alker a disservice by suggesting she has not done her homework, but she claims to have spent ‘11 years working as a rock journalist for BBC Radio 6’. As someone who chafed at being called a rock journalist by the likes of Richard Hell and Colin Escott, I’m pretty sure such journos write (or wrote) for journals – not radio.

To write a chapter on No Wave and make no mention of Suicide, the electro-pop duo who used the term ‘punk’ nine years before No Wave and directly influenced the Human League (consciously modelled on this New York predecessor), Depeche Mode, Soft Cell and the Pet Shop Boys, suggests this is a collection of articles on music Alker likes and artists she admires, disguised as a history of 20th-century music. Real histories connect dots not some of the time but all of it. Faber published just such a book last year, Joe Boyd’s monumental And the Roots of Rhythm Remain.

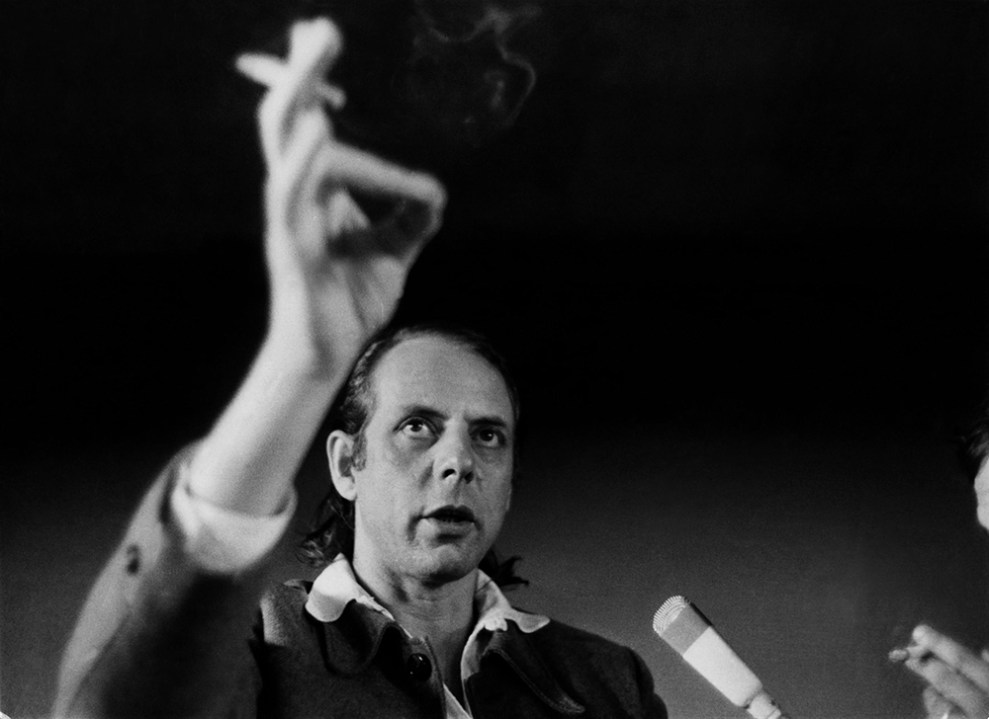

The chapter ‘Transported by the Drone’ is where I engage, and where most rock fans will venture in: the Velvet Underground – ‘Venus in Furs’. I have certainly never forgotten the visceral jolt I got when hearing said track on a crappy MGM compilation containing the two VU songs I knew – both via Bowie. Context is for once provided by a pithy quote Alker gleaned from an interview with John Cale in 2017, revealing how it was he who fused Copeland, Cage and La Monte Young and gave pop ‘the drone’:

Lou brought sheets of lyrics… The songs were all written on acoustic guitar… But I wanted to present ourselves as having a vision… We were determined and really stubborn about putting the drone in there.

Now that’s a moment in time; the sound of cathartic collision between classical and contemporary in music’s equivalent of a particle accelerator. Nor need it be alone. Many rivers to cross: like Krautrockers Can, tutored by Stockhausen, influencing post-punk pioneers PiL (whose guitarist used to roadie for Yes), or the seismic impact of early Pere Ubu singles (featuring future DNA co-founder Tim Wright and the classically influenced synth-player Allen Ravenstine) on Joy Division, Gang of Four, the Fall, etc. No need to go through tunnels uptown or down dead-end streets. Some 20th-century electronic pioneers really did influence pop while making records still found in more record emporiums than those of Lydia Lunch.

Comments