David Keenan acquired his craft as a music writer, he says, from reading the crème de la crème of critics who milked rock music for all it was worth during the 1970s – Lester Bangs, Griel Marcus, Paul Morley, Biba Kopf – before deciding that rock criticism was not his bag. In the preface to this weighty collection of his music journalism, he says he considered himself more of a ‘rock evangelist’. The pieces originally appeared between 1998, when Keenan was writing for hardcore music magazines such as Melody Maker, MOJO and the Wire, and 2015, after which he checked out of regular reviewing duties to pursue his career as a novelist. Luckily for him, his debut novel This Is Memorial Device proved a smash hit.

He dedicates Volcanic Tongue to ur-rocker Lou Reed, but the point is pressed that stylistic labels barely compute to Keenan, and there are lengthy and insightful pieces about free jazz, folk and modern composition too. Concerned not so much with the technical nuts and bolts driving music forwards, or re-examining existing mythomanias, Keenan is instead motivated to capture ‘the first rush of hearing’ and the attitudes behind – even forming – the sounds. Rock, he says, tends towards collapsing into nostalgia. But tracing what he terms the rock and roll ‘urge’ elsewhere has taken him far beyond rock – towards other music unafraid to work itself out in the moment of playing.

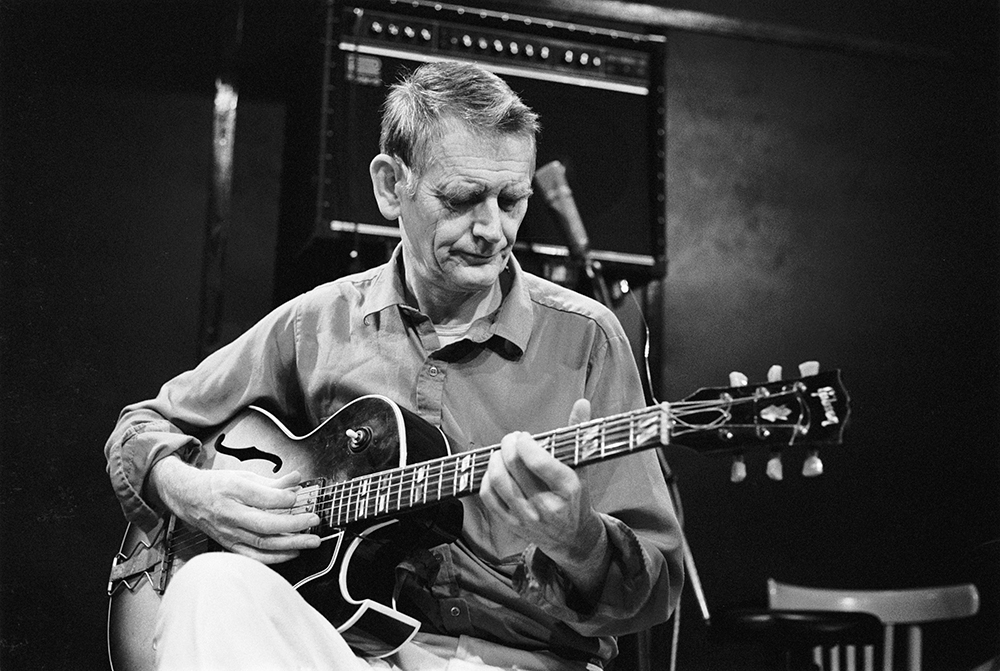

Keenan’s interview with the free-improviser guitarist Derek Bailey, when it was published in the Wire in 2004, made me grasp the extent to which Bailey’s inquisitive, nigglingly provocative music was an extension of his acerbic wit. Bailey began as a jazz guitarist in the late 1950s, with a taste for Charlie Christian and Wes Montgomery, before the 12-tone music of Anton Webern opened his ears to new structures over which improvisation could play out. By the time Keenan interviewed Bailey, he had moved from Hackney to Barcelona and his opening salvo – ‘just what Spain needs, another fucking guitarist’ – says as much as those witheringly dry, deadpan shrugs that defined his music.

The interview became notorious for Bailey’s assertion that jazz died alongside Charlie Parker in 1955, when actually the ‘death’ Bailey mourned was jazz becoming overly formalised – increasingly a sequence of set pieces, he thought, no longer willing to embrace nascent chaos. In a slice of personal memoir, Keenan recalls the ‘beautiful shambles’ of the first gig he ever attended, in Airdrie, when the Scottish indie group the Pastels came to town. Guitar strings snapped and amps stopped amplifying, but the raw-boned sound of the group stirred Keenan’s soul. They were making music despite, not because, of technique, which gave him a sense of belonging: ‘Here was something I could be part of.’

We read about Captain Beefheart throwing everything he already understands about music overboard and about the experimental Krautrock band Faust carefully calibrating the music they want to make – anything to avoid sounds solidifying into predictable patterns and regular ways of doing. A piece about the Memphis-born composer Ellen Fullman, famous for her self-invented 21-metre ‘Long String Instrument’ which she massaged with her fingers to sustain throbbing drones, celebrates the ambition of music that generates itself out of deep listening rather than following any score. Everyone has their roots, though, and Keenan reminds us of the legacy of Memphis blues, of the visceral twang of guitar strings, notes twisted out of scalic alignment, which remains deeply embedded in Fullman. His writing, too, is highly strung in the best sense – resonant with ideas and alert to the rhythm and fundamental tonalities of the music he’s engaging with. This is a personal credo on the power of listening and on how writing about music changed Keenan’s life.

Comments