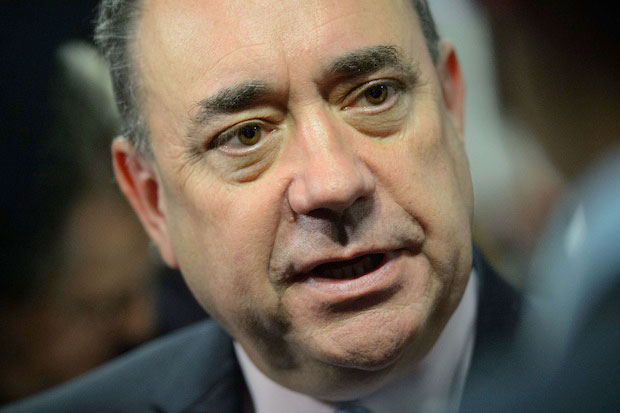

It was just after the Tory party conference last year that I met Alex Salmond. Not alone, obviously, but as one of a group of about 15 people. The group contained quite a few dignitaries, some of them Scottish, so he gave us the full court press. Lunch at his official residence, preceded by a 45-minute reception. The First Minister was there for the duration, ladling out the charm like heather honey.

I’ve met a few senior politicians in my time, including the last three British prime ministers, and Salmond was easily the most impressive. It’s customary on these sorts of occasions for the politician to work the room, spending a few moments with each person. It’s a well-established routine — you’re introduced by an assistant, eye contact is established, your hand is shaken, you’re asked a few questions that are supposed to indicate that the politician knows exactly who you are (they’ve usually just been briefed by the intermediary), and they end by saying ‘Nice to see you’ (never ‘Nice to meet you’ in case you’ve met before).

In Primary Colours, Joe Klein’s book about Bill Clinton, he describes this ritual as ‘the threshold act, the beginning of politics’. It’s not just about making the person feel like they’re the centre of the room, which is relatively easy. The tricky part is to do this while simultaneously letting them feel the full force of your magnetic personality. The most successful politicians project an aura of public power and then make people feel special by admitting them into their private sanctum, albeit for just 30 seconds. The aim is to make them feel like an individual, recognised for their personal worth, and then leave them dazzled by your personal charisma — empower them and enslave them at the same time. Alan Clark used the term ‘Führer Kontakt’ when describing Margaret Thatcher’s ability to do this, but it’s a skill that most successful democratic politicians possess, not just tyrants and dictators.

Alex Salmond, it soon became clear, is a true artist when it comes to this ‘threshold act’. As a unionist and a Tory, I wasn’t well disposed towards him, but after he’d fixed me with his political tractor beam I was almost ready to join the nationalist cause. Auberon Waugh said of his father that he had the effect on people of making them want to please him. That’s exactly how I felt after meeting the First Minister.

It wasn’t just the handshake. After he’d been introduced to everyone, he stood to one side and, without having to tap his spoon on his glass, the room just seemed to naturally settle into silence. He then spent the next 20 minutes or so delivering what must have been a set piece, although it contained so much warmth and apparent spontaneity it didn’t seem remotely rehearsed. He began by telling us about the portrait of Robert Burns above the door. No other paintings of Burns exist, yet we could be confident this was a good likeness because the forensics department of Dundee University had recreated his head from a mold of his skull.

He then moved to the next painting, which was of Tom Johnston, the secretary of state for Scotland during the second world war. With a twinkle in his eye, Salmond told us that Johnston was a socialist and an advocate of home rule who had written a book in 1909 attacking the Anglo-Scottish aristocracy called Our Scots Noble Families. However, after his appointment as Scottish secretary, Johnston went round painstakingly buying up every copy to demonstrate his willingness to put aside political differences in the face of the Nazi threat.

As Salmond continued to work his way around the room, talking about each painting in turn, it became clear we were being given a potted history of Scotland and Scottish nationalism. In his characteristically soft-spoken way, he was trying to explain how he’d arrived at his position and convey something of the romance of the SNP. The subtext was: this isn’t the crude, blood-and-soil nationalism that tore Europe asunder and that civilised people like you have come to fear. Rather, it’s a gentle movement rooted in history and tradition and with a distinguished literary heritage.

All hokum in my view, but hokum delivered with a skill and artistry that few other politicians can match. If a portrait of Salmond joins the others on the walls of the official residence, it will be due in no small part to his mastery of these elementary political rituals.

Toby Young is associate editor of The Spectator.

Comments