Few bluesmen have matched the success of John Mayall, ‘the godfather of British blues’, who died on Monday aged 90 at his home in California. In a career spanning more than six decades, he made 50-odd albums with an ever-changing incarnation of his band, the Bluesbreakers. His proselytisation of black American artists like Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and Otis Rush, gave these legends a new audience this side of the Atlantic. BB King is said to have remarked that, were it not for Mayall, ‘a lot of us black musicians in America would still be catchin’ the hell that we caught long before.’

Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, founded in the early Sixties, was a carousel for some of the world’s most notable blues and rock musicians, many of whom went on to greatness. Eric Clapton and Jack Bruce left the Bluesbreakers to form Cream; and Peter Green, Mick Fleetwood and John McVie departed to form Fleetwood Mac. The Rolling Stones recruited Mick Taylor as their lead guitarist from the Bluesbreakers after they fired Brian Jones.

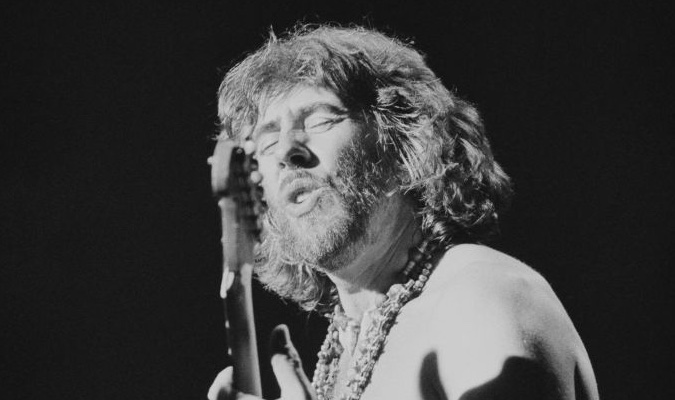

I sat down with Mayall in a café before one of his shows at a small theatre in St Albans, during an anniversary tour to celebrate his 80th birthday. The interview never appeared in print: I was a student at the time, and after unsuccessfully hawking it around various places, it was left on the cutting floor. After his death, I’ve dug it back up.

John Mayall was born in Macclesfield, Cheshire, on 29 November 1933. It was in the family home where the seeds of his success were sown. His father, Murray Mayall, a clerk, amateur jazz guitarist and music enthusiast, impressed on the young Mayall the importance of the genre that would come to define his life: ‘The blues was the music that I grew up listening to. It was in the house. It all came from my father’s record collection.’ His ‘first love’, he told me, were boogie-woogie piano players, like Albert Ammons, who inspired Mayall to teach himself to play the piano, before he moved on to learn the ukulele, harmonica and electric guitar. He did three years of national service, before going to art school and qualifying as a graphic designer.

He looked back on this time fondly: ‘It was an age of young people who were discovering black American music. Prior to that it was New Orleans jazz and it was time for a change, and it was very exciting to see all these bands coming in. Many of them are still around today.’

He formed his first band, the Powerhouse Four, in 1956 and later joined Blues Syndicate before Alexis Korner, the notable British bluesman, persuaded Mayall, then 30, to move to London in 1963. Korner, another big name in the British blues scene, helped Mayall make contacts in the capital. By 1963, Mayall’s outfit was billed as the Bluesbreakers. In 1965 he recruited Eric Clapton, who had just left the Yardbirds, and recorded what would become Mayall’s most revered body of work: the debut LP, Blues Breakers (Rolling Stone ranked it 195 on its 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list in 2003.) The cover features a young Clapton reading Beano on the cover and led to his ‘guitar god’ status.

After Clapton left in 1966, this was followed up by A Hard Road, featuring a young Peter Green in Clapton’s shoes. (For anyone interested in just how exciting this incarnation was, listen to the three live recordings available from 1967). Green later left, taking Mayall’s rhythm section of John McVie and Mick Fleetwood with him to form Fleetwood Mac. Mick Taylor then stepped into Green’s shoes before later leaving for the Rolling Stones. Encouraged by his success in the US, Mayall left Britain for Laurel Canyon in California in 1969 where he paused the Bluesbreakers for the next decade; drinking heavily replaced making music.

Clapton later reflected that Mayall had ‘run an incredibly great school for musicians’, a sentiment echoed by Taylor (‘There’s no better way to learn how to play blues guitar than playing with John Mayall.’) Was Mayall aware that these young guitarists would become such masters of their crafts when he first came across them? ‘As a bandleader you know these things,’ he told me. ‘You know what sort of player you are looking for, and it becomes very easy for you. It always has been easy for me. All bandleaders will tell you the same thing. It is an instinctual thing… These musicians are all very special to me’.

The moniker, ‘godfather of British Blues’ was, however, not one that sat easy with Mayall. ‘I don’t have a choice in the title,’ he said. ‘It has been given to me – it is a label that has been applied to me over the years and kept on.’ When I pressed him on this, he conceded that his role as a bandleader meant he had played a godfather role to many young players. ‘I was a bandleader, and I have always been a bandleader. So that’s the role of what a bandleader does. You just provide the right framework for them to play, and that’s all you can do. It is something you don’t think about with the right people, it just blends together naturally.’

‘I was a bandleader, and I have always been a bandleader

He told me that he didn’t maintain much in the way of relations with his former bandmates. ‘Unless they come see me on tour, then it is very unlikely they will come see me.’ One musician he mentioned specifically who he hadn’t seen for a long time was Peter Green. The Fleetwood Mac founder, who died in 2020, was one of rock’s first and most famous casualties. After suffering an acid-induced breakdown in the late 1960s he disappeared from the limelight and spent decades in and out of mental institutions before a small-time comeback in the late 1990s which continued for a decade or so. ‘He doesn’t communicate with anybody,’ Mayall said. ‘I haven’t any idea what he is doing. It’s troubling but it has been going on for years. It all happened decades ago. There is a limit to how long you can mourn. His greatest work was in the Sixties and it will always be remembered.’ Fast forward to 2020, just before the pandemic struck and five months before Green himself died, Mayall paid tribute to his old guitarist at the London Palladium as part of an all-star tribute concert organised by Mick Fleetwood to celebrate Green’s music.

One of the questions I asked Mayall was whether he was concerned at the blues’ declining popularity. Mayall, who is due to be inducted in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame later this year, was, in fact, optimistic. There’s ‘lots of hope’ for the blues still, he reflected. ‘It is very encouraging that there are so many young people playing instruments now. Just look around you – people are responding to the blues all over the world.’ The widely commercial success of blues-based musicians around today, such as Joe Bonamassa (who paid tribute to Mayall earlier this week: ‘Rest in peace my friend’) and John Mayer, suggests he wasn’t wrong.

Staying on the road was what kept Mayall alive, he told me. ‘The music is a revitalising thing. It is very invigorating and if you play with the right people, it is a great thrill… I like being on the road, it’s what I do. I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t enjoy it. The music comes out of the enjoyment of playing.’

As the interview wrapped up, I tried to get something meaningful out of him in my naive young hack fashion (he’d been pretty grouchy throughout; I’d be, too, talking with a twenty-something trainee). How did he want people to view him within the blues canon? ‘Just to be remembered,’ he said. ‘And for people to listen to my body of work, because it is the story of a life.’

Well, he certainly succeeded in that.

Comments