After a stellar career in the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), better known as MI6, an unassuming man with a passion for bridge and a taste for malt whisky was in line to become head of that service, or ‘C’. The year was 1990. Roger Horrell was the favoured candidate to assume control of Britain’s foreign intelligence service.

Roger had been a friend since we met in Africa some 20 years earlier. I knew him as an MI6 officer but had no idea that he was destined to become Britain’s master spy. Looking back at our regular club dinners in London, he may have hinted at his likely promotion but that is easy to say now. As befits his calling, Roger was a very secret man.

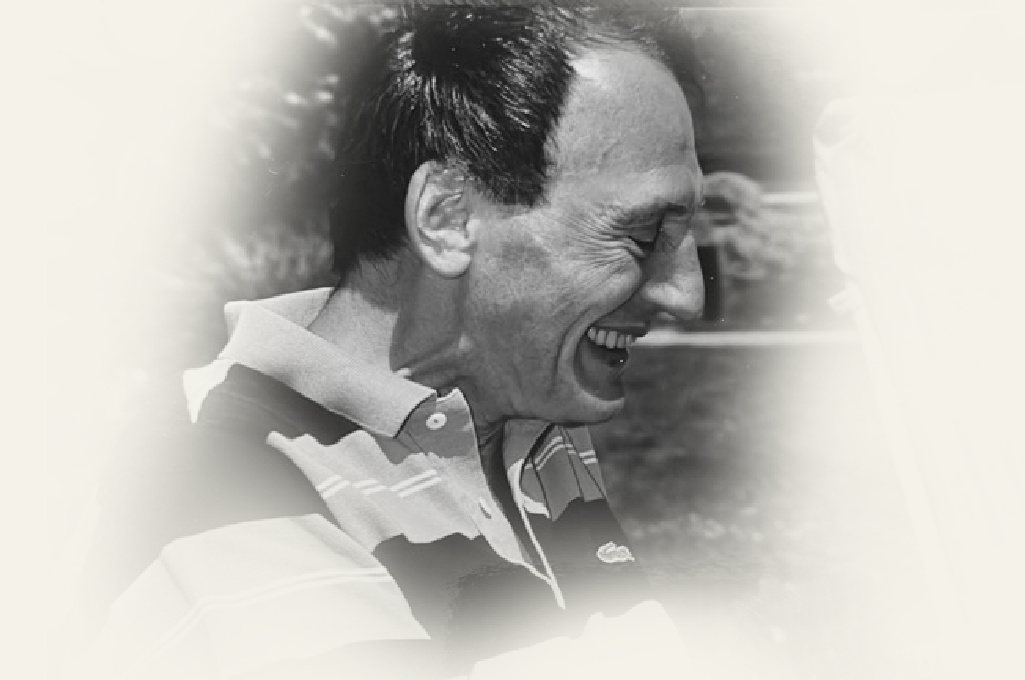

Behind his stories about life in the Kenyan bush, there was someone else – a more private person

I did however know that my friend had been recognised as an MI6 highflier since the success of the Lancaster House conference on Rhodesia in 1980 to which he made a major contribution. What I did not know, and neither did anyone in MI6, was that Roger’s swift rise was to lead to disgrace and departure from a world he had served so well.

There was no hint of that sad finale to a brilliant career when Sir Colin McColl, head of MI6, named three candidates to replace him on his retirement. Roger was recognised within the service as the favourite. The final choice rested with Sir Percy Craddock, foreign affairs adviser to the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher.

Craddock turned all three down, airily explaining that none had a ‘Whitehall profile’ and that he had not heard of any one of them. To general surprise and some irritation, McColl continued as ‘C’ for two more years.

Roger shared the general frustration. He cloaked his feelings with the graveyard discretion common to all in the service. He was now close to the retirement age of 55. He would only have continued in the SIS had he been appointed to head it.

His career had been shaped by two years working largely on his own as a district officer in the colonial service in Kenya. This was the 1950s, when large swaths of the country were only loosely controlled from Nairobi. Kenya’s independence in 1963 ended the posting. MI6, which had noted Roger’s grasp of local African politics and his impressive record governing remote areas of the country entirely on his own, recruited him.

Roger’s first posting under diplomatic cover was to Dubai, then administered by Britain. It was a chaotic and violent time in the Middle East and something of a baptism of fire for the 26-year-old new recruit to the shadowy world of espionage.

Roger proved himself well able to deal with the complex and often contradictory politics of a region fired up by President Nasser’s calls for revolution. He did not, however, speak Arabic and was grateful to be sent next to Africa, his first and last love.

Based initially in the Ugandan capital of Kampala, Roger was posted to Lusaka in Zambia in 1976. There he quickly learned that rival black nationalist groups were more adept at fighting each other than in taking the battle to Ian Smith’s white regime in neighbouring Rhodesia.

As the declared MI6 head of station in the Zambian capital, Roger had to overcome initial suspicion and sometimes the outright hostility of the various nationalist groups. Britain was distrusted and deemed responsible for the rebel regime in Salisbury. With obvious sincerity and the ability to listen for hours over warm beer, Roger slowly won the trust of key elements of these groups. He genuinely liked such opposed political leaders as James Chikerema, Herbert Chitepo and Jason Moyo. They liked him in turn. Their secrets soon became his.

Both Moyo and Chitepo were assassinated by Rhodesian agents in Zambia while Roger was in post. The killings drove him on. He was soon able to provide valuable insights into the tactics, rivalries and personalities of the rival groupings. The leadership in MI6’s grim Century House headquarters in south London was impressed.

It was in Lusaka in 1976 that I first met this man who was to become a friend and remain so long after his untimely exit from the intelligence service. I did not know it at the time, but his marriage to his wife Patricia had broken up. Their two children, Oliver and Melissa, were being schooled in the UK.

Despite a profession that stamps its agents with social caution and often loneliness, Roger was never one for monkish solitude. In Zambia he mixed socially with black politicians and the diplomatic crowd. Young women in the High Commission found his hawkish good looks attractive. He was more than merely attentive to their interest.

But behind the smoky blur of his endless cigarettes, his stories about life in the Kenyan bush and his unbridled admiration for Winston Churchill, there was someone else – a more private and rather different person.

With few exceptions Roger steered clear of the posse of journalists based at Lusaka’s Intercontinental Hotel. I was one of the exceptions. Looking back, I cannot remember how we met, but that was very much the way he worked. He simply appeared from time to time. I might be having an early beer at the bar of the Intercontinental, or a meal alone in a roadhouse, when suddenly there he would be. Cynics might say that his interest was that I was based in the Rhodesian capital, Salisbury, with freedom to travel to the frontline states of Angola, Mozambique, Botswana and Zambia. As a Guardian correspondent I had favoured access in such countries. They may have been right, but our friendship lasted long after his career ended so painfully years later.

Only gradually and naively did I realise that Roger was no ordinary diplomat

Only gradually and naively did I realise that Roger was no ordinary diplomat. He was casually interested in my travels in the region. Looking back, I offered very few insights that he did not already know.

MI6 had an overload of intelligence from Rhodesia. Ken Flower, the head of the Rhodesian Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO), and Derek ‘Robbie’ Robinson, head of the Special Branch, were both passing information to MI6, unknown to each other.

Thus British intelligence was well briefed on the Rhodesian battlefield situation, arms supplies, sanctions operations and plummeting white morale. The crucial question was the political allegiance of Rhodesia’s six million black population. This was a puzzle not least because the Rhodesian army had successfully recruited a second battalion of the all black but white-officered African Rifles. Recruitment had been heavily oversubscribed. Young African men were signing up to be trained to fight black guerrillas for a white rebel regime. Why?

In whatever bar we happened to be, Roger would gently raise the question. I would give an evasive answer. For my part, I wanted to know just how far Britain would go in trying to cut the Russian-backed Robert Mugabe out of any Rhodesian settlement. He would smile and give an evasive answer. We would return to our whiskies.

The Lancaster House conference in 1979-80 ended a slaughterhouse war with a peaceful transition of power – an achievement widely regarded as miraculous. The foreign secretary, David Owen, was among many in Whitehall who privately paid tribute to Roger’s guiding hand in negotiations with the obdurate nationalists. Roger had worked closely with colleagues stationed under diplomatic cover in various African capitals, especially Mozambique; together they had the contacts crucial to the success of the talks.

I was covering the conference that winter in London and had not seen Roger for months. In my mind he remained in Africa. Suddenly, he appeared without warning. I had been sleeping on the couch at a friend’s flat in Chelsea because the Guardian saw no reason to provide me with a hotel room in my hometown. No one knew where I was.

My colleague Patrick Keatley and I had been invited to a supposedly secret lunch in a private Bayswater flat with Mugabe and his military commander Josiah Tongogara. I was walking down Gloucester Road to take a Tube to the rendezvous when Roger appeared out of the blue. He feigned surprise at our meeting and suggested coffee in a nearby café. He merely smiled when I in turn expressed my surprise at his Houdini-like appearance. What interested him was not theviews of Mugabe, whose crypto-Marxist politics were well known, but Tongogara, a brilliant guerrilla commander rightly assumed to be ambitious for the top job and probably prepared to kill for it.

In the event, the lunch provided nothing but poor food and platitudes. I didn’t bother to ask how my MI6 friend had managed to find me amid London’s seething multitudes. I would only get that evasive smile again.

Garlanded with praise after the conference, Roger was reassigned to MI6 headquarters where, after undertaking two important jobs, he was promoted to Controller Africa before being promoted again to become one of the five MI6 directors, heading the crucial role of personnel and administration. The role was vital because it controlled recruitment, making it a stepping stone to the top job.

This was the period when I began to know the man behind the mask. At least I thought I did. Together, Roger and I exchange-dined at our clubs, the Reform for him and Garrick for me. He joined my wife and me at the theatre on several occasions. On these outings he was accompanied by the same woman friend, whom we never really got to know. He visited us on family holidays in the country and enjoyed long liquid lunches there with our friends. We often talked about our Africans days, since we both looked back to that time in our lives with nostalgic regret.

Then came the fall. Roger, now in his mid-fifties, a devoted father with a past as a ladies’ man in Africa, was secretly leading a gay lifestyle.

The malign treatment of a senior officer was widely regarded within MI6 as motivated by personal malice

The cruel irony of the situation was that Roger was betrayed by a fellow gay MI6 officer. The service had recently agreed to allow gay men to ‘come out’ with the proviso that none would be sent to a posting where homosexuality was illegal. Several officers declared themselves. Roger remained silent.

He made the huge mistake of propositioning his fellow officer in the lavatories at MI6 headquarters. His colleague not only reported the incident but said he had seen Roger at gay pick-up clubs.

For someone so senior in the service there was a clear blackmail risk in such a lifestyle. That alone did not account for the shock felt by his friends and colleagues. Ever the private man, Roger had successfully kept the biggest secret of a secret life to himself. He was ordered to resign without thanks for his achievements; nor was there any right of appeal. The usual arrangement for retiring senior officers of a well-paid private-sector job was withdrawn.

It had been initially arranged that Roger would become a leader writer on a national newspaper. The offer was scrapped. The malign treatment of a successful senior officer was widely regarded within MI6 as spiteful and motivated by personal malice.

I soon learned of this fall from grace from a colleague. I invited Roger to dinner. It was a strained conversation until he told me after much wine he had left the secret service. Was I aware of that and more importantly did I know why? I lied and said no. It was a stupid decision because I suspect Roger well knew I was lying. But neither of us wanted to confront a truth that was painful for both.

As far as gender politics are concerned, I count myself a liberal. But I could not bear to hear how a man who had risked so much for his country – and there were personal risks in his African work – had betrayed the secret service he had served so well. But was it really a betrayal? Roger had exposed himself to the risk of blackmail, but the marital indiscretions of other officers had been equally compromising. Nothing was done in such cases.

Had Roger really placed himself and his colleagues in jeopardy? ‘Of course not,’ said a senior retired MI6 officer to me recently. ‘The idea that Horrell would have surrendered to blackmail is ludicrous.’

In the following years we remained in touch, drank wine together and reminisced. His tragedy did not dim our friendship and he seemed remarkably calm about the manner in which a life’s work had ended.

After a lifetime of smoking, emphysema took its toll. Roger was forced to give up his regular bridge sessions in London’s club-land and remained confined to his home in Walton-on-Thames. There I took him packed lunches while he provided the wine. The intelligent, vibrant and very private man I had known in Africa faded away. His ex-wife and daughter came over from the US to care for him. He died in May 2021. A long and laudatory obituary in the Times praised every stage of his career. The reason for his sudden early retirement was not mentioned.

Looking back, I ask myself whether I really knew a man who had been a friend for almost 40 years. The answer sadly is no, and I doubt if anyone did. But if anyone can retain happy memories of a man who lived a life of deception and intrigue, who deceived meas much as his colleagues, I was that person.

Comments