It was roughly 55 years ago, at the tail end of the 1960s, that I took the monumental decision to become a writer. It wasn’t exactly an agonising one. By then I’d been on the European tennis circuit for a decade, and was kaput.

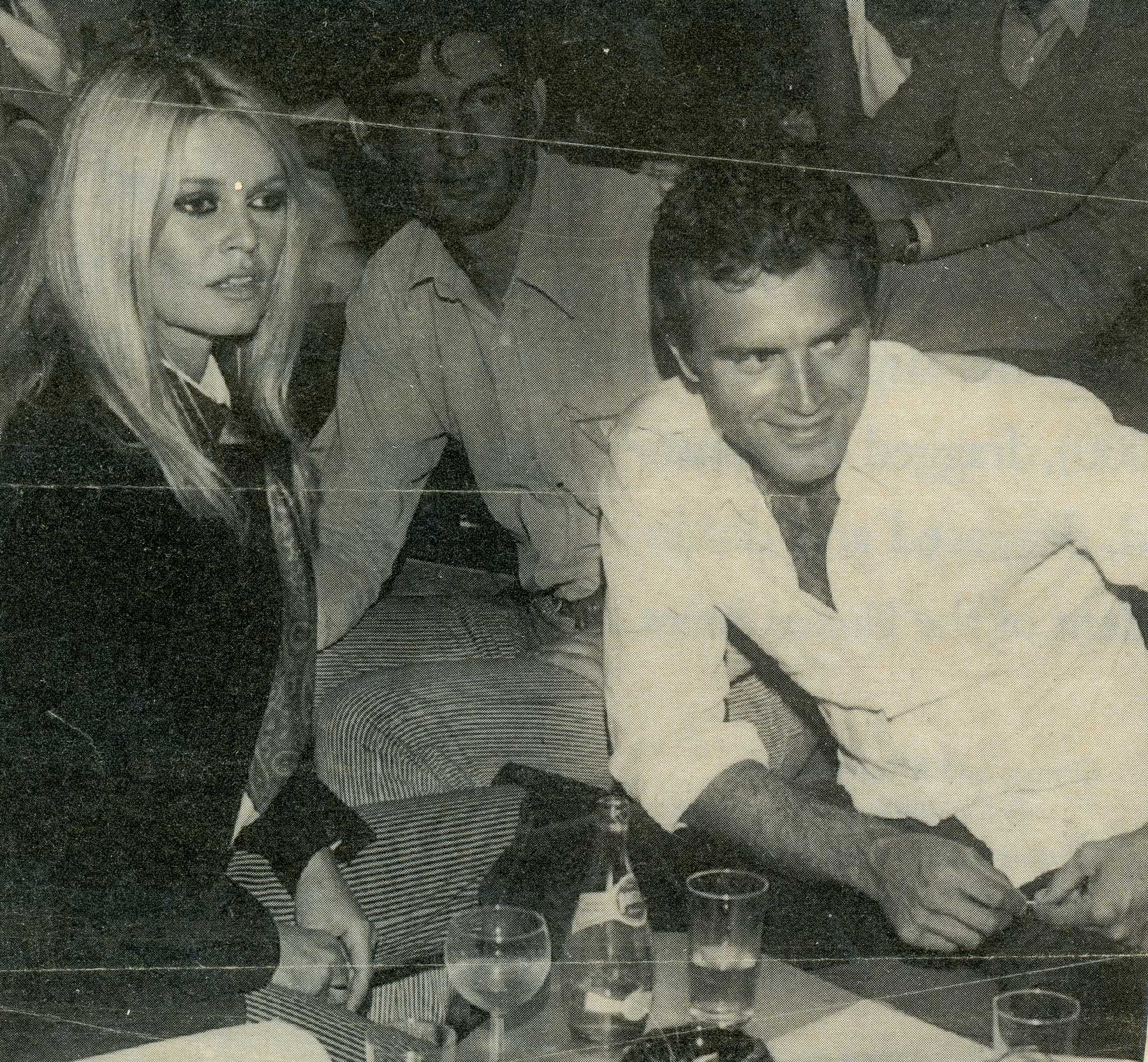

Joining the circuit at 19, I travelled non-stop seeing the world. I was never tired or hungover no matter how much I partied – and I partied relentlessly. And, needless to say, there were constant thump-thumps in the heart, as at every opportunity I pursued beautiful women.

Right out of the box, I found writing easy. Well, it was not exactly writing; copying is the better word

I had a great advantage in this regard. As one of the worst players on the circuit, I was usually free to pursue the fairer sex by the second day of the tournament. To the losers go the spoils! Except in those days the females who followed tennis looked more like losers than the losers.

Still, there were legends of the sport to give one hope. Frank Shields Snr, grandfather of Brooke, was a renowned drinker and womaniser, and recalled as the best-looking man of his or any generation. He once followed a woman to Le Havre, where she boarded a transatlantic liner, and spent the night with her. In the morning he realised he was 200 miles out and that there was no way for him to return to Paris in time to play the Davis Cup doubles against Borotra and Brugnon, and the Yanks had to forfeit the match. But he had not a moment’s regret. Nor, under similar circumstances, would have I.

It is said that romantic love, by its nature, is delusional and brief, a fine madness. I agree. It also thrives on danger, and it is this that excites me. Nothing is more vivid than the start of a love affair.

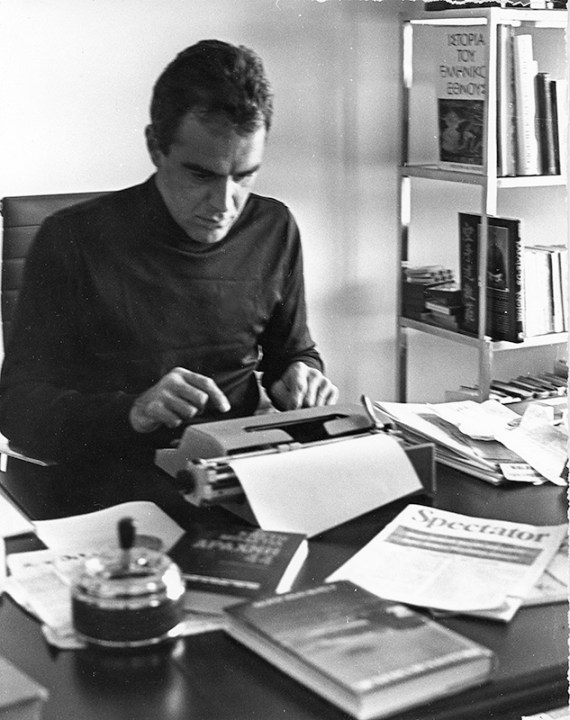

Right out of the box, I found writing easy. Well, it was not exactly writing; copying is the better word. But it did get me some instant attention. When an editor I knew asked me to write a story about the Paris polo season, I bought the International Herald Tribune and copied a racy type of reportage about the English polo season. Another hawk-eyed editor spotted the fact that the only things that differed from the story that had appeared three days previously was the name of the city, the names of the players and, of course, those of the horses. The instant attention came as a result of the editor circulating my copy around the room. It seems I had even left in some typographical errors, and my honesty made me a sort of legend for a while. I beat a hasty retreat from Paris to London.

William F. Buckley finally took pity on me and hired me as an intrepid foreign correspondent for National Review. At the time NR was the numero-uno right-wing magazine in the US of A, as opposed to the Republican party journal it later became (for there’s a great difference), and Bill Buckley’s writings were some of my favourite pickings. But his expectations were high, and English not being my first language, I thought the game was up for good.

That is when Bill’s then 12-year-old son came to the rescue. Christopher Buckley admired my style. By this I mean he admired the girls I ran around with, my skiing, the drinks and cigarettes I offered him when his parents weren’t around, as well as the tales I spun concerning the myriad Hollywood movie actresses who had fallen for my charm. In return for his admiration I asked very little. Only that after his parents had gone to bed, he would edit some of the copy I would be presenting to his father in the morning. Well, no, let’s be more accurate. Christopher actually rewrote everything. But he never changed the basic idea, nor my name.

This was an excellent arrangement, and was further enhanced by my marriage to my first wife, for whom Christo carried a torch. His ogling only encouraged his enthusiasm for my prose.

So writing was great fun that first winter I worked for Bill. But it didn’t last long. When Christopher went off to school in New England I had to come clean to his dad, who actually used my unedited copy in lectures to students on how not to write. But Bill was a devout Christian, and felt sorry for me, so kept me on. He merely suggested that if I was not willing to return to school to master proper English usage, I at least try to learn by listening closely to the sound of good English.

Of course, it also helped even more that Bill and I had become close social friends, since we both spent the winter months in Gstaad, where he’d have me to literary lunches between ski runs with the likes of Alistair Horne, Dmitri Nabokov, Natacha Stewart and the movie star and memoirist par excellence David Niven. Bill would ring early in the morning and suggest a run somewhere, then he’d pick an inn in the vicinity where we’d meet David and Natacha, two non-skiers, and that was that. Buckley always referred to me as Führer, as I would zoom ahead first, followed by him and Alistair Horne, less steady on their skis, and at times near out of control.

Natacha wrote for the New Yorker – it was still a well-written weekly, not the race- and transgender-obsessed leftie vehicle of today – and her main gripe was with having to put off attempts at editing. She would not permit so much as an iota of her material to be changed, and her pen, once the mood took her, could make poor me envy her as if she were Ava Gardner (an obsession of mine back then). My stuff was supposedly the second-most heavily edited copy in the magazine’s storied history, behind only that of a German intellectual with a double-barrelled name whose English was equally indecipherable when spoken. Alistair Horne offered the helpful suggestion that in lieu of journalism, I perhaps should try history. ‘The Greek civil war, Taakhi,’ he’d say, ‘you should try that.’

But I pressed on, and gradually got the hang of it. Two wars in the Middle East and two trips to Vietnam for NR were brief interludes in my playboy life. But my real coming out was getting sent to Algeria to interview leading Black Panthers, including Eldridge Cleaver, who’d fled America after killing cops and was under house arrest. The killer quote from the homesick Cleaver: ‘Oh, man, what wouldn’t I give for a hamburger and a black piece of ass!’ National Review made it a cover story and I was on my way.

In 1977, I was invited to write a column for The Spectator, Britain’s pre-eminent magazine for reportage and social commentary. Beginning a column for such a publication was like the first date with a girl you’ve had your eye on for a long time but never had the courage to ask out. It was a daunting prospect and a severe test of the nerves. The Spectator’s smallish audience was educated, sophisticated and highly demanding, so it was almost like sending my weekly dispatches to an eccentric, unpredictable relation – one’s Aunt Agatha, who graduated Oxford at age 16.

Still, landing the column could not have come at a better time. I had just met the woman I was to marry and have children with, those two events combining to turn me from an immature adolescent into some kind of man. Until I joined The Spectator, I had lived the most undisciplined of lives. Yes, I had made a modest name for myself competing for my country in sport, and had done some journalism, including as a foreign correspondent. But my true accomplishments were chasing women, spending time in nightclubs, and raising hell in a dinner jacket.

The weekly column and its demands anchored my life and went as far as to give me a purpose. Indeed, High Life, as it was called, became the centre of my existence. The fear of old ghosts drove me toward an ironclad ritual of never missing a column. There’d be only one miss in the next 45 years – not counting a ten-week leave of absence as Her Majesty’s guest in Pentonville Prison, following an unfortunate encounter involving white powder and an airport customs officer – the streak broken only when an assistant editor spiked a piece fearing I had libelled Jeffrey Epstein.

Speccie editors gave free rein to the columnists, and mine wandered anywhere I chose, from high society to sport to politics – American, British, Greek – and, of course, to the topic ever closest to my heart, the fairer sex. Culture back then did not yet put a premium on grievance, oppression and victimhood, and when the libel writs followed in my wake Javert-like, The Spectator invariably showed spine.

My High Life column led to other goodies – American publications such as Esquire and Vanity Fair hired me, as did Rupert Murdoch’s Sunday Times in London and the New York Post on the other side of the pond. ‘Write the way you do for The Spectator,’ said Rupert.

But those other places were never quite as comfortable a fit. The audiences were different. Vanity Fair and magazines like it appeal mostly to brain-dead dollies who don’t know the difference between Rimbaud and Rambo, and they lack Speccie readers’ well-developed sense of humour.

True, I also did a fair bit of undermining myself. Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown spiked my very first column when I used it to review my own book. In retrospect, I suppose she wasn’t wrong. I don’t know why it is, but whenever faced with having to write for someone I’ve never written for before, I get the jitters – the same kind one gets just before getting into bed with someone very special. Self-conscious prose is like self-conscious lovemaking. No good.

For a week I drank, and for the week after that, I chased after girls well below my usual standard

Tina Brown later wrote about yours truly that ‘there are a lot of hacks who would like to be ship-owners, but there are no ship-owners who would like to be hacks’. It was the nicest thing she ever wrote about me, and for once she got it right. Even my father used to laugh about it, if a bit incredulously. ‘Don’t you realise that journalists make their living through blackmail?’

At Esquire, I very nearly got canned before I even started. I pulled a prank on the magazine’s co-editors by launching a rumour via unsigned memo regarding their sexuality. Word passed down that the perpetrator would not only be fired, but he or she would also be sued. I was saved by a plump cutie-pie, then doing a stint as a copy girl on her semester off from Yale, who was the only one who knew the identity of the guilty party. The cutie-pie was Jodie Foster, and she took her secret back with her to Hollywood.

In the end, five years was the limit I spent writing for any of those other publications. But even at those places, I always tried to write with a free spirit and open heart, saying what I wanted to say, which I regard as the truth, and letting the chips fall wherever. It hardly needs saying that some of it aroused strong reactions, especially, and ever more so with the passing of the years, my attitude about relations between the sexes. For despite all the noise to the contrary, I regard it as beyond dispute that men are not by nature monogamous, and that the romantic feelings that launch them into marriage tend to be less durable than a secondhand Mercedes. Furthermore, I have taken it as my mission to publicly defend that most marginalised of contemporary species, the ardent womaniser.

I have accepted the inevitable slings and arrows and lived with the consequences.

True enough, when my Esquire column was terminated, I didn’t take it particularly well. For a week I drank, and for the week after that, I chased after girls well below my usual standard. But then, facing matters head on, I accepted that this was the hack’s life, sobered up, and went back to my wife and children. And c’est tout.

Taki’s memoir, The Last Alpha Male: the Amorous Pursuits and High Life of a Poor Little Greek Boy, is out now.

Comments