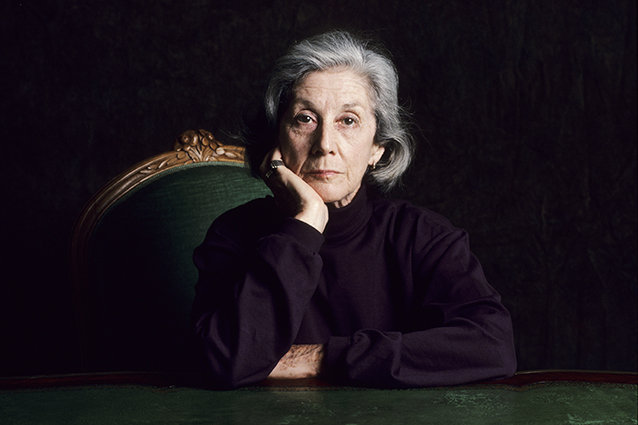

Spectator reviewers over the years have had a difficult time with Nadine Gordimer’s books. Gordimer (1923 – 2014), who won the Nobel Prize for literature and was one of the leading campaigners against apartheid, has died at the age of 90. Her books are passionately political and sometimes maddeningly abstract; some found them poetic, others were infuriated. Livingstone’s Companions in 1972 was a great book, Douglas Dunn wrote at the time.

‘There is so much intelligence being brought to bear in her work that revulsion or criticism is never pious or direct but almost invisibly balanced by ironies, by the natural moral of fiction itself. Indignation is constantly being toned down by sympathy for the general human condition. She is always more interested in people and what makes them happy and unhappy than in political moralities, although the political concern is there… the language is scrupulous and poetic, a poetry of actuality, not of the fabulous. This is also true of less atmospheric stories about love and loneliness, such as “A Third Presence” and “The Life of the Imagination” — there is such a ripe, memorable blending of several situations that the effect is a genuine poetic realism.’

But not everyone was intoxicated. Writing just before South Africa’s first fully representative election, Andrew Kenny hoped Gordimer might finally stop writing books.

‘Under apartheid, South Africa developed what must be the world’s most boring literature with such excruciatingly dull writers as Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee. Now, thank goodness, we need no longer pretend to read their dreadful books nor attend the execrable ‘protest theatre’. For all these things we are truly grateful.’

She carried on getting readers though, and in 2003, Sebastian Smee was just as rude, describing getting through her latest collection of short stories Loot as a ‘pleasureless slog’ of wading through ‘sense-jamming punctuation and pointless asides’. Reviewing the novel Get A Life, Digby Durrant had a similar complaint a couple of years later.

‘Sometimes it’s more like translating than reading. Sentences have to be read slowly and re-read equally slowly. It’s as if to write a simple sentence is an error of taste or sloppy thinking. Gordimer strains too hard for an originality a writer of her stature doesn’t need: “Without the accompanying happening of a child”… “She is that persona who has no need of convictions”. Writers can be forgiven their peccadilloes but where were her editors?’

When she was writing essays, Gordimer allowed herself to express herself on her favourite themes in a more straightforward way, and consequently her critics didn’t get so irritated. In 1988, Laurence Lerner found some interesting ideas in her collection of essays, The Essential Gesture.

‘The essay on “A Writer’s Freedom”… asserts that freedom from censorship is not enough: there must also be freedom from what is expected of him by his allies and admirers. For the black South African writer, this means that “the jargon of struggle, derived internationally” is not “deep enough, flexible enough, cutting enough” for the poet or novelist, even though they consider themselves – and are considered – part of the struggle… She quotes Marquez claiming that the revolutionary duty of the writer is to write well. All this takes us into a world that has lost its urgency for English writers.’

In 2010, Justin Cartwright, who knew Gordimer, reviewed an 800-page collection of her non-fiction, pointing out that she didn’t believe there was a distinction between politics and literature and that serious writers should only tackle weighty subjects.

‘She has an utterly admirable determination: in an appreciation of Paz she is really describing her credo: “Octavio Paz was one of those superb poets whose brilliance makes nonsense of the notion that taking on the turmoil and conflict in one’s society corrupts and destroys true creativity.” In this one sentence you have both the essence of Gordimer and you see her sensitivity to the idea that she is somehow tied to a political party, for better or for worse. She prefers to think of “values that are beyond history”.’

Comments