Andrew Lambirth meets the artist John Hubbard, whose work is concerned with atmosphere and the spirit of place

John Hubbard makes paintings about landscape which draw upon his early training in America and the influence of the Abstract Expressionists. But his pictures are far from abstract images: they are about the play of light through foliage or the surface of rock seen close to. They are concerned with atmosphere and the spirit of place — with earth, air, light and sometimes water interacting. He denies that these are aerial views, asserting that his paintings try to capture the experience of being in the landscape, rather than looking down upon it, and being in it over a period of time. ‘I came to prefer an image that reveals itself gradually, by stages,’ he says, ‘like so much of nature.’

Hubbard was born in 1931 in Ridgefield, Connecticut, took his BA in English at Harvard in 1953, was based in Japan for his military service (1953–6), then studied for a couple of years at the Art Students’ League in New York. His move from a general arts background to a career in painting was encouraged by working with Hans Hofmann at his legendary Provincetown summer school, even though (or perhaps because) Hofmann was highly critical of Hubbard’s efforts. At that time de Kooning was Hubbard’s hero, but in New York landscape was not thought a fit subject for painting. So in 1958 Hubbard moved to Rome and based himself there, painting still-life and street markets for the next two years, and travelling in Europe. Landscape painting began at last to seem a possibility.

In 1960 he moved to England, marrying and settling in Dorset the following year. His work at this point was still very experimental, and the small de Staël-influenced landscapes he had made in the south of France seemed quite inappropriate to his new life. For the first time he had settled close to the subject of his work, and he moved into a style and scale more fitting to it. He made big paintings, calling on all the formal freedoms he had learned from the Abstract Expressionists.

I went to meet Hubbard at Roche Court, an imposing 19th-century country house set in Wiltshire parkland, in the village of East Winterslow, outside Salisbury. This is the home of the New Art Centre, a commercial gallery founded in 1958 in London, which relocated here in 1994. Between 1961 and 1975, Hubbard held nine solo exhibitions at the New Art Centre in Sloane Street. Over the following decades he continued to exhibit widely in Britain and America, showing in London with Fischer Fine Art and latterly Marlborough Fine Art. Now he is back at Roche Court, with a group of landscapes from the 1960s. This is not so much a retrospective as a re-examination of selected pictures after nearly half a century. One or two have been exhibited before, others have never previously left the artist’s studio.

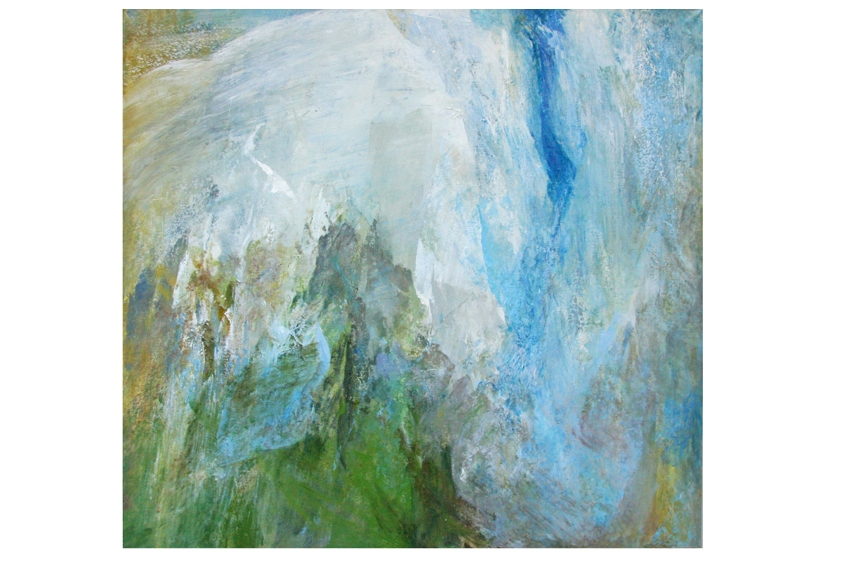

The exhibition, which runs until 15 April, consists of half-a-dozen large oils on canvas and several much smaller oil-on-paper paintings. They are beautifully installed in a long, light-filled gallery which links the house with an Orangery in the garden. The subjects are general: coastal landscape, rocky woodland, light on a cliff face, and correspond to the all-over paint application Hubbard favours, rather than identifying and focusing on a central image. Interestingly, the paintings that immediately preceded the ones here were more gestural, and more obviously Abstract Expressionist in mood and application. The actual making of the painting was more important in those pictures than the experience of the landscape. The group of works at Roche Court are much more involved with an interpretation of landscape that seems as passionately engaged today as when they were painted.

From the start, Hubbard showed a preference for the contained landscape rather than the scenic prospect: for quarries and caves, rocks and woodland. He liked to suggest water and sky in his paintings, though not always where the spectator might expect to find them (in a vertical strip rather than a horizontal one), but he preferred to concentrate on the textures of stone or foliage. This interest is reflected in his passion for gardens, not only to be seen in his later paintings of subjects fairly local to him such as Abbotsbury (Dorset) and Tresco (the Scilly Isles), as well as gardens further afield such as those of the Alhambra in Spain, but also in terms of his own garden at Chilcombe, near Bridport in Dorset. Although he would not want to be thought of as an artist–plantsman in the mould of Cedric Morris or John Nash, his garden is nevertheless essential to him, and reinforces the notion of a special and intense relationship with a particular stretch of landscape that is found in so much of his work.

Materials and their specific properties are important to him. He started these Sixties’ paintings by working in turpentine-thinned oil paint on fine prepared canvas. ‘Sometimes you get a good beginning,’ he says, ‘but sometimes a good beginning can be a snare and a delusion. You have to try something else.’ Hubbard talks lucidly but in the most general terms about ‘establishing the character’ of a painting, or giving it ‘a different life’. He tends to work thinly, though with selected areas of paint build-up, because he wants to keep in (literal) touch with the canvas, and thus with the reality of the picture as a painted surface, rather than a low relief sculpture in pigment. ‘My painting idol is Rubens — in terms of how to paint, not subject matter. I love Rubens’s sketches and the fluidity of his paint.’

Studied at close quarters, Hubbard’s paintings have a marvellous textural range and vitality: he has applied the thinner paint swiftly, dripping it here and there, thrown or spattered it, and then administered it thicker with a palette knife. There are months of work in each painting, which might later be revised if Hubbard was unsatisfied with the final result. Formally, these are ambitious and impressive works, but they don’t just exist in abstract terms. They are also intimate and searching explorations of the nature of landscape as it changes under variable light, and as paintings of place they are remarkable. Seen from the garden through the glass wall of the gallery, their subjects change and become more elemental: distance brings out different emphases in their structures. Here be waterfalls, storms, mountains, spring torrents, great blocks of alpine air. And yet they are actually more local images, the kind to be experienced by driving along the coast roads of Dorset.

By 1968 Hubbard was getting restless with painting the English landscape. A commission to design décor and costumes for the Dutch National Ballet helped to free him up. Then in 1969 he made his first visit to Morocco and the Atlas Mountains, and his work changed again. For the next 40 years, he pursued an elusive goal, going ever deeper into landscape, exploring structure and pattern and detail. All his life John Hubbard has been searching for a sense of place: not one particular place, but a recognition of the special qualities of a series of places that have intrigued and beguiled him through a long and distinguished career. These 1960s landscape paintings mark the point at which his mature vision really took off.

Comments