On my desk is the vertebra of a narwhal. It was given to me by a man in Canada after a convivial dinner. Narwhals are Arctic whales with long spiky tusks on their noses. This vertebra is about three inches across, embedded in bone expanding into waisted wings, like a propeller. If I were the award-winning Scots poet Kathleen Jamie I would be describing it better.

A whale vertebra, for her, felt ‘grainy, not quite cold’, and smelt of wax crayons, which are, or were, made of whale oil. She was in the Whale Hall of the Natural History Museum in Bergen where the dusty skeletons of 24 whales hung by chains from the ceiling. They were being cleaned, before removal to a modern display. She sat under the jaw of a blue whale, ‘as if under an awning’; she sat inside a humpback’s ribcage and helped scrape the gunge from the bones with toothpick, toothbrush and sponge. Compared with this intimacy of access, the currently fashionable ‘interactive’ displays, usually on a screen, are nowhere.

Sightlines is a collection of essays about how to see what one is looking at. What is nature, Jamie asks, where does it reside, what is it we are being exhorted to ‘reconnect’ with? The kind of nature writing with which she is making a name for herself is a subset of travel writing, some of it internal. Her mother’s death provokes her into visiting the cut-up room of a path lab, to watch the consultant slicing finely a length of diseased colon — images of food-processing here — and looking through a microscope at organs which resemble pink landscapes of estuaries and sandbanks. ‘Bad’ things like bacteria and cancerous cells ‘have no purpose. They are not conscious. They just are.’

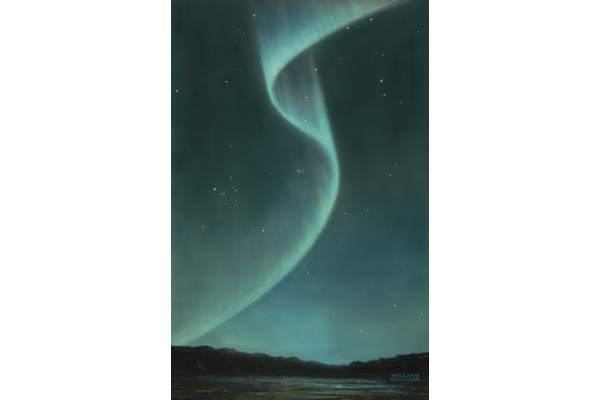

The mindless neutrality of the natural world, whatever its beauty, is her main theme. The actual landscapes she inhabits and investigates are intransigently northern. In the Arctic to see the aurora borealis in the teeth of a ‘katabatic’ wind, she acknowledges the ‘colossal, witless indifference’ of icebergs. It is not only the skill of seeing that she is on about. All the senses can be developed. Some people can smell icebergs, and hear the aurora borealis. She does not pretend to special powers, though she ‘heard’ perfect silence, ‘a radiant silence’, on the tundra. She responds lyrically to the ‘white cascade’ of a dead swan’s open wing, as to a whale’s vertebra lying among sea-pansies on an uninhabited Hebridean island, and to the corpse of a ringed storm petrel — ‘an ounce of a bird’, which had made 24 migratory trips across the Atlantic; but like any normal person she gets cold and exhausted, horribly seasick, sometimes even a bit bored.

She learned to see what she was looking at by hanging out with bird-watchers, concentrating for hours on a 500-foot cliff on the island of Noss covered in screeching gannets, observing ‘their arrivals and departures, bondings, squabbles and fights’. The trick is to keep on looking, even when there is nothing special to see, so that when something unusual happens you notice it. She was rewarded by a sighting of killer whales round the foot of the cliff, as she was again on the island of Rona at seal-pupping time — where she was prepared for a massacre, as the four killers thrashed their the way round the island’s perimeter. But they left untouched the hundreds of seals bobbing about, and raced off again into open sea. Was it a game, or a training exercise? Whales loom large for Jamie. Their bones seem holy. ‘How, these days, do you acquire a whale relic?’ I look at the object on my desk with renewed respect.

Working as a volunteer on a 4,000-year-old neolithic site in Perthshire, she learned to observe microscopically, scraping delicately away with a sharp trowel-edge at one square metre of trench. They found a tomb, and inside it the skeleton of a woman, and a pottery bowl. The bowl is now in a museum, and the woman’s bones in store in a cardboard box. You can’t help feeling she was better off where she was before. We are, says Jamie, ‘a species obsessed with itself and its own past and origins’. We are also part of nature. She accompanied archaeologists and surveyors meticulously measuring and recording an ancient settlement on St Kilda. They read the landscape; most of us are ‘illiterate’.

Why were such settlements abandoned, and recolonised, and abandoned again? People lived on St Kilda until 1930, stitching their clothes with feathers. The end could come because of a boat not arriving in time, a plague of rats, some unknown catastrophe, even ‘improvements’. The homes on the islands were windowless, and built into the earth, against the weather. An improving landlord provided regular houses — which were hopeless, because where would people find glass when the windows broke, or roof-tiles, or timber on an almost treeless island?

Jamie questions the lazy way we think about such places and about the past. For island people, the sea is a way, a conduit, not a barrier. Once there were no ‘wild animals’ because all animals were wild. She does not like the facile use of the word ‘remote’. Remote from what? It is to deny some other human beings their sense of centre.

There is some autobiography in this book, and the experiences Kathleen Jamie recreates cover a span from teenage years to recent times. Some poetic licence is to be inferred from the amount of direct speech and dialogue, unless she goes around with a tape-recorder — unlikely. Some very short pieces are like prose-poems. Sometimes she slips briefly into ‘nature blog’ mode. But the spirit of the book is uncompromising and stony. Sightlines cannot teach us instantaneously to see what we are looking at, but it corrects faulty vision and rams home the message that nature, as she says, is ‘not all primroses and otters’.

Comments