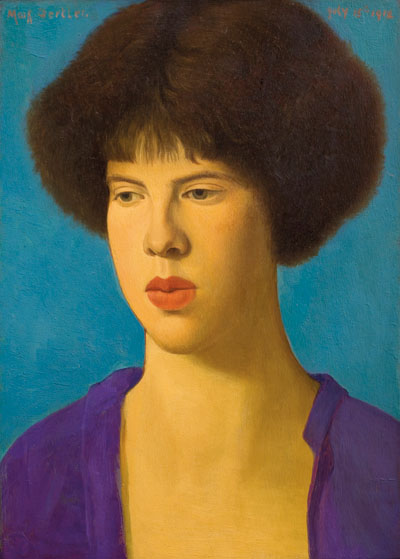

Every so often, about once a decade, the work of Mark Gertler (1891–1939) is rediscovered and exhibited. I remember seeing excellent shows of his work at the Ben Uri Art Gallery in 1982 and in 2002, and at Camden Arts Centre in 1992. Each time a well-selected body of his paintings is gathered together, we are reminded of the extraordinary talent of this young artist, who tragically took his own life. Yet for many of those who care about art, Gertler is still best remembered as the wild bohemian obsessed with the Bloomsbury siren Dora Carrington. Certainly, Gertler’s 1913 portrait of her, a striking example of his Neo-Primitive tempera style in the key of blue, and one of the many treats of this exhibition, doesn’t quite explain the attraction. More beautiful and more mysterious is the girl he portrayed as ‘The Violinist’ in 1912, a painting of seductive colour and mesmeric clarity.

The show opens with ‘The Artist’s Brother Harry, Holding an Apple’, a Gauguinesque postlapsarian come-hither painting of surprising simplicity and much presence. At right-angles hangs a subdued but effective self-portrait of the youthful artist at his easel. Gertler drew like a Renaissance master, as can be seen in his pencil study ‘Old Man with Beard’ on the wall opposite. Here, too, is the very peculiar ‘Creation of Eve’, its focal point the fork of Eve’s widely parted legs. Another superb drawing, this one a study for the famous portrait of Natalie Denny, and then comes a lively oil landscape from 1916, entitled ‘The Pond, Garsington’. X-rays have just revealed that this is in fact painted over the only known oil study for Gertler’s most famous painting, his 1916 anti-war statement ‘The Merry-Go-Round’, now in the Tate. If you look carefully, you can see the outlines of the tented top of the carousel on its side on the left of the picture, coming through the green of the trees. There are many more fine things, and a luxurious hardback catalogue (£25), all of which give a good account of this distinctive artist.

By concentrating on the early period of his achievement, this exhibition makes an acceptable and coherent argument for Gertler’s greatness. It would be interesting to see if a show of his later, more School of Paris paintings would pack the same aesthetic punch. But Piano Nobile has done us a great service by bringing an undeservedly neglected British master back into the limelight. Let us hope the gallery will continue to reacquaint us with the little-known. What about an exhibition of paintings by Alfred Wolmark (1877–1961)? He’s an almost forgotten figure today, though I see that a couple of his radically decorative still lifes are coming up for sale at Sotheby’s Modern and Post-War British Art sale in November. Another figure ripe for reassessment: let’s hope someone takes the time to show him to us properly once again.

At Long & Ryle, Somerset dialect and folk culture infuse Simon Casson’s more usual classical imagery. Casson (born 1965) is a master of baroque fantasy, uniting the fruit or flower still life and allegorical portraiture of Old Master paintings with the squeegee surface gestures of Gerhard Richter. This imagery remains his staple, with landscape, drapery, rabbit masks and roses all playing prominent roles here, but his interpretation has developed new depths. The paint-handling has become less mechanical and more painterly, the squeegee giving way to the hand gesture, with a variety of brush and finger marks, dribbles and further areas of succulent, liquid paintwork and gestural freedom. The overlaid marks interrupt and contradict the fragmentary found images, but somehow the unity of the painting holds. Impressive.

Two more shows that deserve mention, both in Bond Street. At Richard Green’s palatial new gallery is a fine and thought-provoking exhibition bringing together the work of Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore (until 14 November). In the front room, three superb early Moore drawings done in wax crayon and watercolour wash, two from the famous Shelter series and a third that explores ideas for reclining figure sculptures, at once command the visitor’s attention. At the other end of the room is a powerful grouping of a beautiful oval Hepworth alabaster carving, with ‘Curved Form on Red’, 1962, oil and pencil on board, hanging above it. In the second room are three top-quality Nicholson reliefs: ‘December 63 (key circle)’, ‘June 1960 (stone goblet)’ and, perhaps the best, ‘Still Life, 1946’. Six small Moore bronzes, mostly of family groups, are tellingly placed in apsidal niches on the elegant staircase, going up and down. As a bonus, two delicious still-life paintings by William Nicholson, Ben’s father, add a welcome painterly touch to the ensemble, the one of sunflowers in a spotted jug being especially heart-lifting. This is only a sampling of a top-quality exhibition that allows us to compare and contrast the work of three of the greatest British artists of the past century. Recommended.

Across the road at the Fine Art Society (until 8 November) is an equally enjoyable exhibition of the rather neglected painter George Clausen (1852–1944). The son of an immigrant Danish interior decorator and a Scottish mother, Clausen was born in London but moved to the countryside early in his career to paint the field workers in rural Hertfordshire. Heavily influenced by French social realism, and by the paintings of Bastien-Lepage in particular, Clausen developed a versatile style of naturalism. Before this exhibition, I had not realised quite how strong or how various Clausen’s work is. Ranging from the very early Tissot-like urban compositions to the rural heights of ‘The Mowers’ (1891) and ‘Allotment Gardens’ (1899), with their echoes of Jean-François Millet, to the 1920s depictions of misty mornings in Essex, there is much here to delight the eye.

Watercolours, drawings and etchings fill out this portrait of a versatile artist. There are bright and sumptuous still-life paintings, evocative watercolour landscapes, and oils that have something of the flicker and fusion of pastel. Clausen was a dab hand at light — look at ‘A Winter Morning in London’, for instance, a composition radiant with wintry matutinal colour. To coincide with the show, Kenneth McConkey has launched a detailed monograph on the artist (Atelier Books, hardback, £45), entitled George Clausen and the Picture of English Rural Life, which should help to re-establish him firmly in the art-loving public’s awareness.

Comments