A documentary by Nick Broomfield is always to some extent about Nick Broomfield. He has cultivated an image as a gonzo filmmaker, striding into shot holding a boom microphone, headphones clamped over his ears, and in the politest possible way provoking chaos. ‘Unfortunately it comes very easily to me, to be slightly out of control,’ he confesses.

His previous adventures have included getting on the prickly side of South African white supremacist Eugene Terre’Blanche, striking up a strange rapport with the convicted serial killer Aileen Wuornos on death row in Florida, claiming to have worked out who killed the titular gangsta rappers in Biggie & Tupac, and provoking a firestorm of legal threats from Whitney Houston’s estate with his varnish-stripping portrait of the singer, Whitney: Can I Be Me?.

As a 14-year-old schoolboy, Broomfield met Jones on a train and fell into conversation with him

But there’s no glimpse of microphone, headset or indeed Broomfield himself in his latest film, The Stones and Brian Jones. It’s a riveting examination of the photogenic, fair-haired musician who was the original leader of the Rolling Stones before he was pushed aside by the burgeoning double act of Keith Richards and Mick Jagger. Jones died in July 1969, aged 27, seemingly from a combination of drugs, disillusionment and exhaustion. Having initially been the Rolling Stone who received the most fan mail and the most feverish attention from teenage girls, he has been relegated by history to a mere footnote. ‘He barely got a mention in that series of Stones films that was done for their 60th anniversary last year,’ Broomfield notes.

One reason Jones became sidelined was that he lacked the songwriting gifts that allowed Jagger and Richards to create one of the greatest song catalogues in rock’n’roll history. Nonetheless Jones made some vital musical contributions. He experimented with the open guitar tunings he learned from the American bluesmen, and passed on the knowledge to Richards. His eerie slide guitar was the signature sound of the band’s 1964 chart-topper ‘Little Red Rooster’, and he transformed the 1967 hit ‘Ruby Tuesday’ with his haunting contribution on that least rock’n’roll of instruments, the recorder. As veteran Stones bass player Bill Wyman says in the film, ‘he would just pick up anything that was handy and create something out of it that wasn’t there originally.’

But why has Broomfield chosen to make this film now?

‘I’ve done a number of films that have been much more self-reflective in terms of the times I grew up in and so on,’ he says. ‘I did Marianne and Leonard [about Cohen and his lover Marianne Ihlen] which was about the 1960s. I did My Father and Me, and the new one is a part of that, looking back to a formative part of my life, some of my influences.’

‘Jones was really into trains and trainspotting, which was not something that I’d expected’

Broomfield, now in his mid-seventies, had a special interest in the Leonard Cohen story because he, too, had been Marianne Ihlen’s lover, having met her on the Greek island of Hydra in 1968. She even gave him his first acid trip. The film about him and his father Maurice, a renowned industrial photographer, speaks volumes about Maurice’s creative influence on his son and the changing currents of British social history that affected both of them.

With Brian Jones, Broomfield has again found a uniquely personal angle, albeit a narrow one, to help frame his film. As a 14-year-old schoolboy, attending Sidcot school near Winscombe in Somerset, he met Jones on a train and fell into conversation with him.

‘There were all these first-class carriages and he was sitting there by himself and I sort of banged on the window. He was very welcoming and said, “Come in.” I said, “Can I have your autograph?” and he said, “Yeah,” then he said, “Sit down.” It was like he just wanted to have a chat. This was the time when the Stones were urinating on garage walls and all the rest of it, but they were like a great symbol of good behaviour for us lot. Wonderful! Finally somebody’s doing what we want to do! Then the big surprise was that he was really into trains and trainspotting, which was not something that I’d expected. He and Stu [Rolling Stones road manager Ian Stewart] would go and buy bits for their train sets when they were on tour, or go trainspotting together.’

But perhaps what really tickled Broomfield’s filmmaking fancy was not a fascination with vintage rolling stock, but the way that Jones personified the generation gap that yawned at the beginning of the 1960s. He was the well-spoken son of aeronautical engineer Lewis Jones and his wife Louisa, who lived in upper-middle-class comfort in leafy Cheltenham. But while his parents were both musicians steeped in classical music, Brian developed an obsession with the blues. His father noted how Brian underwent a ‘peculiar change’ in his early teens and embarked on a lifestyle of playing in blues clubs, often surviving by billeting himself on the families of a string of girlfriends. The girlfriends frequently ended up becoming pregnant.

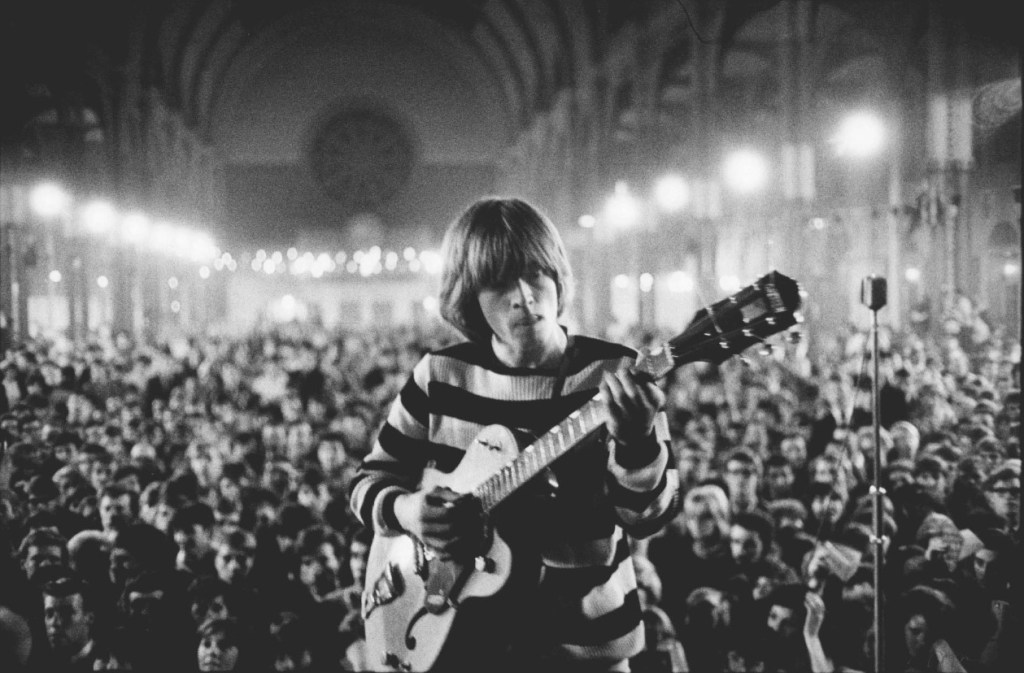

Brian Jones playing at Alexandra Palace in 1964. Photo: John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins

Among other treats, like some illuminating contributions from the Stones’ ex-bass player Bill Wyman and vivid recollections from film director Volker Schlöndorff about the way Anita Pallenberg arrived at the Cannes Film Festival with Jones but left with Keith Richards, the film is a feat of archival research. It’s crammed with magical footage of the nascent Stones, the quaint, monochrome Britain they emerged out of, and their visits to the States, Australia and Europe. Scenes of delirious, shrieking fans being shoved and kicked off the stage by bouncers are startling reminders of the unearthly impact of rock’n’roll after the smoggy conformity of the postwar years, as if the Stones and their contemporaries had arrived overhead like cultural dambusters.

Broomfield spent two-and-a-half years unearthing all this material, much of which has never been seen since it was originally shot. ‘I think that the great explosion of art and design and music that was so profound in the 1960s is much more circumscribed now,’ he says. ‘The possibilities are much more controlled than they were. Now, all the material would be owned by somebody and impossible to license or use.’

Similarly, he had no interest in approaching streaming giants like Netflix or Amazon to get the Jones film funded. ‘Netflix are incredibly conservative and their first question would be: “Has the band signed off on this?” If you said: “Well, no actually, because I’m going to make something that’s unauthorised”, they would tell you to take a running jump.’

So he’s grateful to the BBC for sticking by him through the project. ‘They rather like it when it’s not authorised and it’s going to be a much more honest, unblinkered look at something,’ he maintains.

What makes Broomfield so valuable as a filmmaker is his willingness to dive in and make something happen, the more unexpected the better. He cites as influences such pioneering documentarists as Donn Pennebaker, Richard Leacock and Frederick Wiseman, but also references Gay Talese’s famous 1966 feature for American Esquire, ‘Frank Sinatra Has A Cold’.

Talese arrived in LA tasked with interviewing Sinatra, who claimed to have a cold and refused to speak to the writer. Talese constructed his piece by spending three months observing Sinatra wherever he could and talking to members of his entourage. The article came to be viewed as a benchmark of the so-called New Journalism.

‘It was about the way in which you get the story is the way that reveals stuff about people,’ says Broomfield. ‘I think documentary is all about the spontaneous and the unexpected and the moment, and the American streaming networks on the whole have scripted pieces with a beginning, a middle and an end before they start. I always think: “How can you possibly know the end when it hasn’t happened?” Hopefully you’re going to come up with an end which is totally brilliant and unexpected and is a revelation to you and the audience.’

Happily, Broomfield found a powerful little evidence-bomb that gives The Stones and Brian Jones a sting in its tail. It’s a long-lost letter from Jones’s father containing a heartfelt apologia for his failure to understand his son and praying for his forgiveness. ‘I have been a very poor and intolerant father in many ways,’ he wrote.

‘It’s incredibly tender and painful at the same time,’ says Broomfield. ‘It was a very difficult time, I guess, to be a parent. People born on the other side of World War Two had such a different view of the world, the world changed so much in that time and there was such a generational conflict.’

Broomfield found this a difficult film to make, but he feels he’s learned something from it.

‘I’ve never made a film that was this archive-heavy, so that’s a particular discipline that is just exhausting. I can’t tell you how relieved I am to get it out… I obviously hope that my approach will have a following and rub off on people, or the films I’ve made will be a good reference point and a way of looking at the last few decades. But there’s always a better film to make, or a better story that you haven’t done.’

The Stones and Brian Jones is available on BBC iPlayer.

Comments