What does it take to bury an outdated argument? The thought occurred while reading Motherland, one of a series of recent books seemingly haunted by the ghost of Hugh Trevor-Roper.

Back in 1964, Trevor-Roper, an expert on the English Civil War and the Third Reich, made the mistake of opining on African history. There was nothing much to teach, he said, other than the history of Europeans in Africa. ‘The rest is largely darkness… And darkness is not a subject for history.’ He then added insult to injury with a snitty reference to the ‘unrewarding gyrations of barbarous tribes’. These were silly remarks; but Trevor-Roper was the man who later authenticated the Hitler diaries, so not above the odd clanger. They were also comments voiced more than 60 years ago, when far less was known in the West about the continent’s rich and diverse past.

But that lofty dismissal seems to enjoy extraordinary staying power, for hard on the heels of the Sudanese-British television presenter Zeinab Badawi’s An African History of Africa comes Motherland, by Luke Pepera, a young British historian and broadcaster with Ghanaian roots. Both seem preoccupied with demolishing the Trevor-Roper canard.

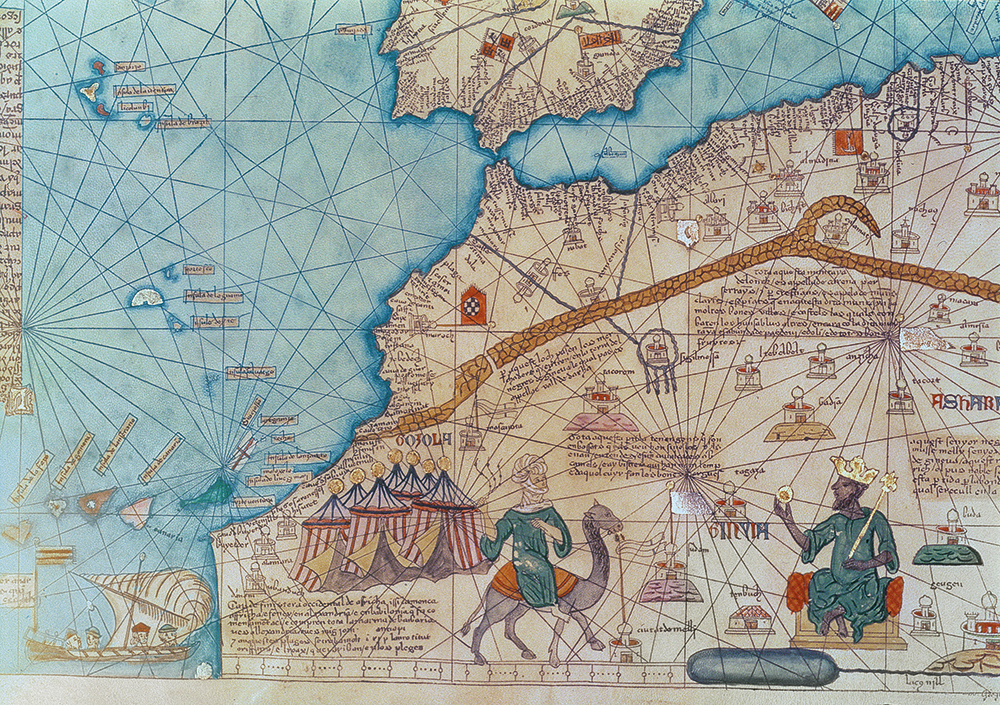

Like Badawi’s book, which kicked off with ‘Lucy’, the skeleton of Australopithecus afarensis on display in an Addis Ababa museum, Motherland reaches back into the mists of time. To drive home the depth and breadth of African history, Pepera focuses on the Mandingo emperor Kanku Musa Keita’s 60,000-man, 100-camel pilgrimage to Mecca in 1323, which first brought Mali to international attention. We also hear the Moroccan diplomat Al-Wazzan’s dazzled account of life in Timbuktu, the jewel of the Songhay empire, captured back in 1512.

But the book really comes alive when Pepera abandons the plod of chronological storytelling and leaps nimbly between past and present. A chapter on ancestor worship explains Akan and Yoruba reincarnation beliefs, illustrating that in Africa the barrier between the living and the dead is always permeable. That triggers a rabbit-hole dive into the career of the American actor Chadwick Boseman, who played T’Challa in the Black Panther superhero film when dying of cancer. If Ghanaians live on in the Asante nation’s royal stool, Boseman lives on in that iconic performance, in which – poignantly – the plot has T’Challa repeatedly conversing with ancestors in the spirit world, a realm the actor himself was about to enter.

In one of his strongest chapters, Pepera explores oral storytelling – of primordial importance in many African cultures. He traces the modern rap battle (born in 1981 at the Harlem World Club in New York) back to Ikocha Nkocha insult games played by Nigeria’s Igbo and riddling contests popular across the continent. From there he skips to proverbs, the linchpins of any African conversation, before examining the role of griots, west African praise singers, poets and genealogists. The juxtaposition of modern and ancient is bracing and fun.

In Africa, the barrier between the living and the dead is always permeable

There are times when Pepera’s appreciation of alternative value systems falls into Rousseau’s ‘noble savage’ trap, in which whatever is neither western nor modern is presumed benign. I raised an eyebrow reading his enthusiastic account of the role of oracles and divination in healing damaged community relationships. I still recall the Congolese orphanage I once wrote about, full of children whose poverty-stricken parents had thrown them onto the streets after a witchdoctor declared that one child had ‘bewitched’ a family member. Such practices aren’t always ‘healing’.

Pepera also wastes his energies dismantling what I suspect are straw-man arguments. Take his final chapter, which challenges what he claims is the misunderstanding that ‘in the 17th and 18th centuries, like European merchants, every African ruler sought to profit from the transatlantic slave trade’. Perhaps I spend too much time reading the Guardian, but my impression is that much of the British public these days lays the blame for the slave trade on its own white ancestors. It’s the notion that African rulers played any role that often comes as a surprise.

My main criticism, though, is that too often Pepera does what I have been frequently warned against doing: extrapolating from one region he knows very well – west Africa – to a continent whose 54 nations boast a multitude of ethnic roots, religions, customs, languages and colonial experiences. You can never be too wary of African generalisations.

Overall, this is a curate’s egg of a book – idiosyncratic, surprising, brilliant in parts, stodgy in others, full of thought-provoking comparisons and provocative claims not all of which bear scrutiny. I look forward to Pepera’s next book, in which, having driven a stake through Trevor-Roper’s heart in this work, he will no doubt beat his own intriguing path.

Comments