When it comes to Stonehenge, we are like children continually asking why and never getting a conclusive answer. There are plenty of theories as to its purpose, ranging from the ludicrous to the dull, but perhaps we would be better off concentrating, as in this excellent book, more on how our ancestors got the stones up in the first place.

Attention has always centred on the original bluestones which made up the first circle at Stonehenge, because they were brought, remarkably, all the way from Wales. These are the smaller – but still two-ton – megaliths, carved from the Preseli quarries in Pembrokeshire. It used to be thought they must have been transported by water, around the considerable circuit of the south-west coast and then up the River Avon. Archaeological consensus has now shifted towards them having been brought 220 miles overland, however difficult – in fact possibly, and perversely in keeping with our national temperament, precisely because it was so difficult and therefore the achievement would be the greater.

As superb recent investigations by Mike Parker Pearson have shown, these stones did not come direct from the quarry but were first put up as an original bluestone circle in Wales at a site called Waun Mawr – so were transferred, for reasons which remain resolutely mysterious, lock, stock and barrel to Salisbury Plain, although at least it can be presumed with something of their power of provenance intact. Merlin’s stones indeed, as later antiquarians often dubbed them.

Prehistoric brains were as large as ours and just as capable of complex thought

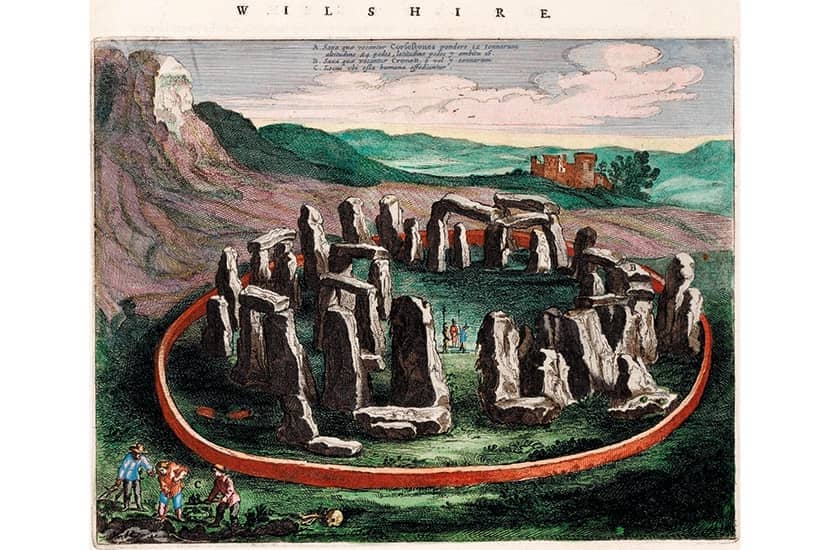

But spectacular an achievement as that was, Mike Pitts rightly concentrates on the larger grey sarsens that arrived later at Stonehenge and formed the familiar horseshoe of trilithons and surrounding capped circle. These came from far closer to hand – the Marlborough Downs, just 17 miles away – yet clocked in at something like ten times the weight, at 20 tons each.

The engineering work necessary to move these giants already boggles the imagination. Pitts also asks how they were erected when they got to their journey’s end, particularly as they were put up in what by then was a congested circle.

We often assume that Stonehenge followed a conceived plan, whereas – something that understandably confused earlier archaeologists – it’s more like a large room in which people moved the furniture around for 1,000 years until they worked out a pattern they liked. And given we’re talking about trilithons, perhaps the analogy should be more like moving grand pianos around on a concert stage when they’ve all got to face the conductor – in this case, the sun.

Pitts’s interesting suggestion is that rather than being lifted up on ropes over an A-frame structure by large teams from afar, difficult in an already crowded space, the stones would have been ‘rocked up’. Wedges would have been inserted under their tops, followed by a long process of pivoting and chocking to get the top up high enough. A final ‘rock’ would then have jostled them into a prepared ground socket, in a method comparable to that used on Easter Island to erect the similar sized Moai.

One can’t help wondering mischievously if the last process ever went wrong: if, having spent months rocking the megalith up near its correct position, a Laurel and Hardy moment occurred on the final push and it went all the way over and down again. Oops.

There’s a useful sign at another Neolithic monument, Newgrange in Ireland, reminding visitors that prehistoric brains were as large as ours and just as capable of complex thought. We patronise them by assuming that because there was no writing to express that thought, they were not capable of extremely intricate concepts. A curator at the splendid World of Stonehenge exhibition currently at the British Museum told me that rather than use the term ‘prehistory’ – which implies little happened, clearly far from the case – perhaps a better term might be ‘deep history’.

Aside from an unnecessarily Ladybird title, this is a fascinating book from someone who has devoted many years to studying the henge – not always an easy thing to do, given previous archaeological research had been so poorly recorded in the 20th century. I was particularly struck by the use of an 18th-century drawing made before one of the trilithons fell over. Pitts makes the observation that over the centuries before the arch was put up again in 1958, visiting tourists seem to have cut off chunks from the corners of the fallen giant.

But before we deplore this vandalism –and English Heritage uses it as yet another excuse to prevent us from getting inside the stones themselves today – it’s worth noting that much the same may have happened in ‘deep history’. It seems our ancestors were also in the habit of chipping off bits from spare bluestones, perhaps as a way of transferring the magical landscape around Stonehenge to their own homes. Reading this book by the fireside is the nearest – and least damaging – modern equivalent.

Comments