Readers of the Bible, you are almost certainly in for a shock. A new book, drawing on recent archaeology and literary criticism, persuasively argues that some of the most important parts of the New Testament were written or edited by slaves. Its author, Candida Moss, presents this thesis in God’s Ghostwriters, a general interest book which asks readers to look beyond the Bible’s named authors and imagine their collaborators, some of whom were enslaved scribes.

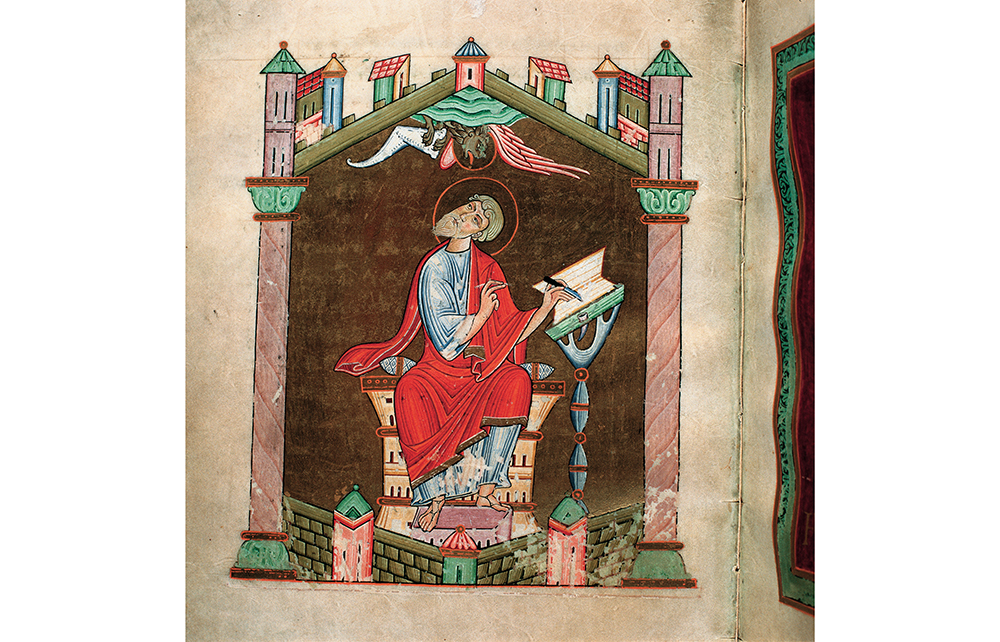

In the Roman era, ‘writers’ did not usually inscribe the text themselves but composed through dictation; and most people who took dictation were enslaved. They were well educated from a young age, and it was customary for them also to act as proofreaders.

St Paul, for one, clearly employed scribes. In his Epistle to the Galatians, he writes: ‘See what large letters I make when I am writing with my own hand.’ The implication, says Moss, is that ‘the preceding section – what amounts to almost the entirety of the letter – had been written by someone else’. Towards the end of the Epistle to the Romans, Paul’s most theologically important work, the text reads: ‘I, Tertius, the writer of this letter, greet you in the Lord.’

Scribal collaboration seems even more important when one considers that Paul composed at least four letters from prison. Recent archaeology has demonstrated that most Roman jails were underground, with a small window. They were cold, damp and barely lit – appalling places to write. Moss argues that, had Paul written his epistles himself in these conditions, the text would have been ‘almost unreadable’. It is much more likely, she says, that he dictated these letters through the window.

In addition to Paul, Moss focuses on the Gospel of Mark – the earliest canonical account of Jesus’s life. Mark was not an apostle, and Church tradition maintains he was a secretary to St Peter, or affiliated with a Petrine group in Rome. Although he writes in Koine Greek (the common tongue of the eastern Mediterranean) and uses some Latinisms, Aramaic is clearly his native language.

These details about Mark’s Gospel are not new, but Moss’s contribution – at least for the non-specialist reader – is to connect them to the status of scribes in the Roman world. Seen through this lens, Mark looks like an archetypal enslaved penman; and Moss posits that he was one of the many forced to leave Aramaic-speaking Judaea during or after the First Jewish-Roman war (66–74 CE).

To develop her argument, she emphasises that subtle references to slavery – such as the four attendants carrying the paralytic man, and Jesus’s injunction that his followers ‘leave their house or brothers or sisters or mother or father or children or fields for my sake and for the sake of the good news’ – suffuse Mark’s Gospel. She also highlights a striking reference to enslavement by Paul who, in Philippians 2:7, describes Christ ‘taking the form of a slave’.

Moss further reminds us that the spread and shape of Christianity was influenced enormously by the scribes who copied biblical texts. She underscores that copying – a lowly task often delegated to menials – produced discrepancies:

No text was ever copied perfectly, and hand-writing can be idiosyncratic and difficult to follow. Those involved in the duplication of texts had to make decisions about words they were replicating. Copyists, therefore, were among the first and most influential interpreters of Christian scripture.

In the second half of the book, Moss digresses from the themes of ghostwriters and the making of the Bible. Her attention to non-biblical texts from early Christianity is excessive, and she regularly strays into eisegesis – the practice of reading ‘into,’ rather than ‘out of’, the text: ‘During his trial, Jesus stayed silent, almost as if, like an enslaved person, he had been trained to hold his tongue.’ Conjecture abounds. The word ‘might’ appears 171 times in the book. And there is unnecessary hectoring. Instead of taking us with her on this journey of learning, Moss begins to lecture. It is disappointing that the reader she seems to have in mind is a dyed-in-the-wool reactionary – someone who almost certainly won’t have picked up her book.

Nevertheless, her massive achievement is to shift the paradigm and tell the early Christian story (as far as is possible) from the perspective of the enslaved. This ought not to challenge the faithful reader. ‘Divine identity,’ she reminds us, ‘is incompatible with enslavement only if one thinks that enslaved people are less valuable than other people.’

Comments