[audioplayer src=”http://rss.acast.com/viewfrom22/merkelstragicmistake/media.mp3″ title=”Kate Maltby and Igor Toronyi-Lalic discuss Benedict Cumberbatch’s Hamlet” startat=1642]

Listen

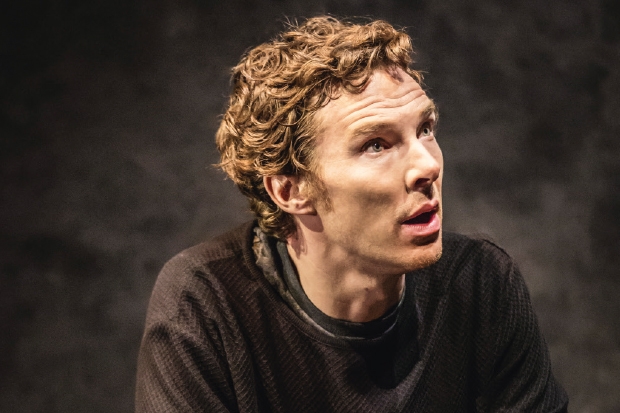

[/audioplayer]You can’t play the part of Hamlet, only parts of Hamlet. And the bits Benedict Cumberbatch offers us are of the highest calibre. He delivers the soliloquies with a meticulous and absorbing clarity like a lawyer in the robing room mastering a brief before his summing-up. And though he’s a decade too old to play the prince (the grave scene sets his age at about 28), he cavorts about the stage like a ballet dancer delighting in his own athleticism. But he’s also much too nice. The darkest shades of melancholy and the raw emotional ugliness are missing. Hamlet is a bereaved, broody malcontent with a profoundly warped sexual outlook whereas Cumberbatch is a different species, a Hollywood star with the world at his feet. His vanity may have persuaded him not to focus on the prince’s misogyny and callowness. The insulting dismissal of Ophelia has more than a hint of tenderness about it. And the cross-examination of Gertrude, in the closet scene, hasn’t enough moral disgust.

Lyndsey Turner’s staging sets out to match the starriness of the lead performer but it risks overwhelming the action. Elsinore is a bombastic fantasy with a mountainous staircase, a Liberace chandelier and ominous walls festooned with weapons, antlers and ancestral portraits. Some of Turner’s innovations work well. Hamlet is first glimpsed alone, in iconic abandonment, brooding over his dead father’s belongings. At the interval a mini-earthquake buries the stage in a mudslide that becomes the jetty from which Ophelia launches her suicide. Other innovations are less successful. Hamlet marks his earliest bout of madness by donning a soldier’s tunic and dragging a toy fort on stage. Later he puts on a native American headdress. ‘The Mouse-trap’ is performed with the prince playing a role in the action with the word ‘KING’ blazoned on his back. These are minor disturbances but they inflict a lot of damage on the splendid fragments Cumberbatch has to offer.

Duncan Macmillan’s drearily named play People, Places and Things is set in a rehab clinic. At first it looks like a public seminar on the virtues of therapy. We meet ‘Emma’ (her identity is uncertain), who peps herself up every morning with a breakfast of wine, vodka, cornflakes, speed and Valium. Then she goes for a drive. Her diet is wrecking her acting career and she’s in a hurry to get sober and get out. Her supervisors, whom she viciously abuses, are themselves all recovering addicts. This sets up a neat discussion about the 12-step programme.

The flashy staging is sometimes effective. As Emma’s brain unscrambles itself, she hallucinates and we see the wall tiles peel away from their surfaces and swim upwards. A doppelgänger climbs out of her bed, a second rolls out from underneath and three further Emmas walk into the room. Her soul is overdosing on addicts. These effects are absorbing but the show still doesn’t feel like a play. And Emma herself is hard to get to grips with. She tells lies constantly and admits to telling lies but this prevents us from surrendering our sympathy to her. As a person she’s about as appealing as a tent full of wasps. Chippy, angry, immature and self-obsessed, she’s ferociously bright and articulate but she refuses to employ her intellect in her own interests. Instead she pursues a dead-end career playing crappy roles in pub theatres. And to pay the bills she takes on even crappier roles as a waitress or a telephone-sales tout. But then she starts to make acute observations. Group therapy, she says jeeringly, is just like a rehearsal. A lot of embittered, self-loathing neurotics sit in a semicircle trying to assume a new identity that doesn’t quite fit. Then she makes a speech describing the mystical allure of acting that is the most eloquent defence of the profession I’ve ever heard. And she explains why actors, who embody transcendent truths on stage, find it so dispiriting to be out of work. This accounts for the great depression and anger in which she’s sinking. Finally, we meet her gruesomely haughty mother whose emotional coldness seems the key to Emma’s character. All that remains is a final encounter with her addiction and when it arrives it delivers an astonishing burst of power.

At the curtain call, the audience leapt to its feet instantly. There’s no mistaking a response like that. The play packs a five-star punch. At the same time it avoids the debate it purports to animate. The truth about addiction is that it springs from self-love, which is best cured by its opposite, selflessness. ‘Help someone needier than you are’ would cure many addictions but it would also threaten the therapy industry. So therapists prescribe continued dependence on therapy. This play is hooked on the same illusion.

Comments