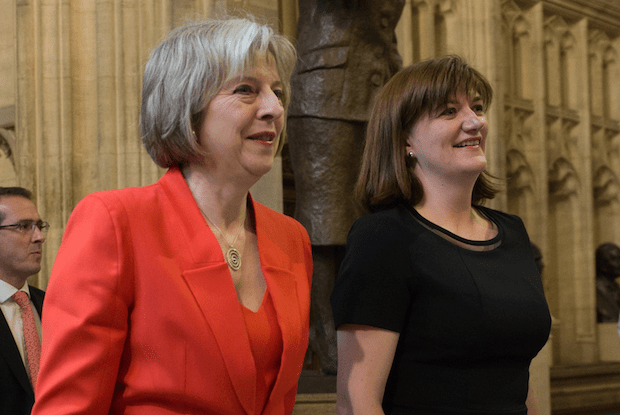

Theresa May took just 15 seconds to sack Nicky Morgan as Education Secretary. Morgan’s revenge has taken a little longer. First, she criticised the Prime Minister’s expensive trousers, but once she’d apologised for that, the Loughborough MP then set herself up as something far more troublesome in the long-term than a fashion critic. Not only is she a prominent campaigner against a Hard Brexit, Morgan is also the chair of the Treasury Select Committee, one of the most powerful backbench operations around.

When we meet in her Commons office, Morgan is busy planning how to make the government’s life uncomfortable through a series of select committee hearings and through a series of amendments to the EU Withdrawal Bill which have landed ministers in a spin. The government was reasonably relaxed about the Second Reading of this Bill because Tory Remainers like Morgan and her colleagues Anna Soubry and Dominic Grieve were keeping their powder dry for the Committee stage of the bill. Now that stage is approaching, and the rebels are ready.

Their main concerns are how much scrutiny Parliament is given, both of the final deal and of the many pieces of secondary legislation that will need to be written to replace EU law. Morgan and her comrades are proposing a triage system for these instruments with a committee deciding whether or not the piece of secondary legislation in question is so technical that it can pass without debate or whether MPs are entitled to have a say on what’s being proposed by the government. ‘There is a worry that one person’s technical amendment is another person’s change in rights, so let’s not have that as an ongoing problem, let’s deal with it, have a committee to look at things so everyone gets a say if they want to,’ she argues, adding that ministers have made clear that on this and on the question of Parliament having a say on the final deal, they are open to changes.

They’ll have to be open to changes, as it’s not just a small handful of Tories who are proposing changes to the scrutiny elements of the withdrawal bill, but Labour as well. Morgan, though, is keen that the Tory attempts to amend the bill have little to do with Jeremy Corbyn’s party. ‘We have been very clear that we are not going to back things that have been put down by Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell.

‘Part of the reason for us putting down our amendments was because we wanted to signify as Conservative backbenchers here are our areas of concern, we’re not just putting our names to amendments from other parties. I think that ministers will also find it easy to deal with it if the lead names on the amendment are from their own side.’ She says she hasn’t spoken to Labour’s Shadow Brexit Secretary Keir Starmer, but that as ‘old lawyers together’, Starmer and Grieve have had discussions on Brexit tactics.

Labour’s interest in the transition period is of less interest to Morgan and her colleagues. ‘I’m not clear that the Bill is the right place in which to discuss that,’ she says. ‘I do understand that, having been a minister, there is difficulty putting stuff into legislation which is being negotiated. I quite understand. Ministers need a free hand knowing that they are accountable to parliament and have to come back and explain to us why they have negotiated in the way they have.’

Brexit isn’t just a test of ministers’ and rebels’ plans: it is a test of politicians’ character. Morgan has just published a book on the importance of character education. Taught Not Caught: Education for the 21st Century looks at schools which are already incorporating character into their lessons, and at the way that character education can help deal with the growing mental health crisis among schoolchildren. Morgan has long been interested in both character and mental health, the latter stemming from what she terms a ‘family interest’. She dismisses my slightly facetious suggestion that Parliament might be an example of what happens when people don’t have character education, but is still very worried about the tone of political debate about the moment, pointing to a rise in hate crime following the referendum and fears among her constituents who are EU citizens that they will have to leave this country that they now call home.

It’s not just people misreading what Britain voting to leave the EU meant. Morgan thinks that those at the heart of politics are to blame too. ‘Things like the ‘crush the saboteurs language and things we saw from Number 10 in Autumn 2016 were very deliberately deaf to the concerns of the 48 per cent,’ she says, referring to Theresa May’s remarks this time last year about ‘citizens of nowhere’. ‘That tone has really coloured and I think it has probably perpetuated some of the division.’

Morgan is hardly a fervent May supporter, and hasn’t been particularly sympathetic to the Prime Minister’s remarks about staying on as leader at the next general election. She argues that ‘I think it’s very difficult for her to be leader at the next election… Let’s not worry about leadership and everything else until this huge project is well completed’.

Does she think about her own leadership prospects now? ‘I can’t see me being the answer to the Conservative Party’s next leadership needs.’ But she’s found the answer to what do after life in government, and it’s an answer that still makes life uncomfortable for May, even if Morgan isn’t challenging her for the leadership.

Comments