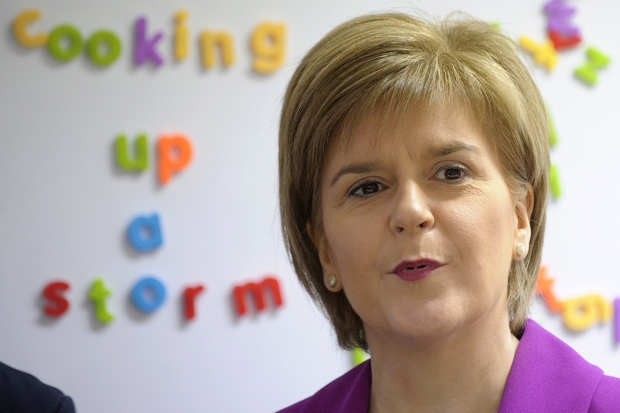

If you’ve glanced at a photograph of Nicola Sturgeon in the past year or two, you won’t have failed to spot a recurring theme. The SNP leader surrounds herself at every opportunity with young people who have been in care. It is Sturgeon’s current cause – with education and social justice having fallen by the wayside. Scotland’s First Minister has been in the job four and a half years and deputy for seven before that. She is in the market for a legacy, and with every passing day it is less likely to be Scottish independence.

Whatever the politics, that Sturgeon has taken an interest is an indisputable good. There are almost 15,000 children in care in Scotland and, between those being cared for by local authorities and those on the child protection register, around one in 50 children north of the Border is being ‘looked after’ by the state. Eighty-eight per cent of young people were referred to the children’s hearing system on care or protection grounds, rather than for criminality, yet somewhere between one third and one half of Scotland’s prison population has been in care. Young people in care are six times more likely to be excluded from school, six times more likely to be unemployed after leaving school and 45 per cent of them suffer from mental ill-health.

Sturgeon has made a decent start on these issues, setting up an independent review of the care system, exempting care-experienced young people from council tax and providing bursaries to help them through further education. She has even taken to calling herself ‘the chief mammy’ and ‘the chief corporate parent’ of Scotland.

However, her championing of children in care has led to some uncomfortable truths about their experiences making it into the public domain. A new report by the charity Who Cares? paints a grim picture of vulnerable children left to fight the system alone for their rights and even denied basic entitlements like access to their parents and other loved-ones. Who Cares? says it is only reaching 7.2 per cent of children in care with independent advocacy and adds:

The offer of advocacy to many care-experienced people is confusing and patchy, with some young people being offered support to be heard by people who work for the same organisation that delivers their care.

That last point appears to show that the past 20 years of advice from every major care service and child abuse inquiry – which have consistently recognised the need for children in care to have access to an independent advocate – is being ignored. As far back as 1998, in response to the Kent Report, the government accepted there had to be ‘greater consistency across Scotland in terms of advocacy services for children’ and, the following year, the Edinburgh Inquiry recommended ‘increased accessibility to workers from the independent Who Cares? organisation’. Similar recommendations were issued by the Kerelaw and Shaw inquiries.

Moreover, the number of in-care children trying to access an advocate has increased year-on-year for the last four years, with family contact the most common reason for seeking out support. However, since 2014, recorded instances of children experiencing difficulty in accessing their parents or siblings have more than doubled. Now, Who Cares? has warned of ‘a need to speed up and deepen’ efforts for these young people, said it would be ‘completely unacceptable’ if these problems aren’t resolved within a decade, and raised the spectre of a ‘forgotten’ generation of people who have gone through the care system. It is polite, cautious, third-sector language for: Enough photo-ops; get your finger out.

Comments