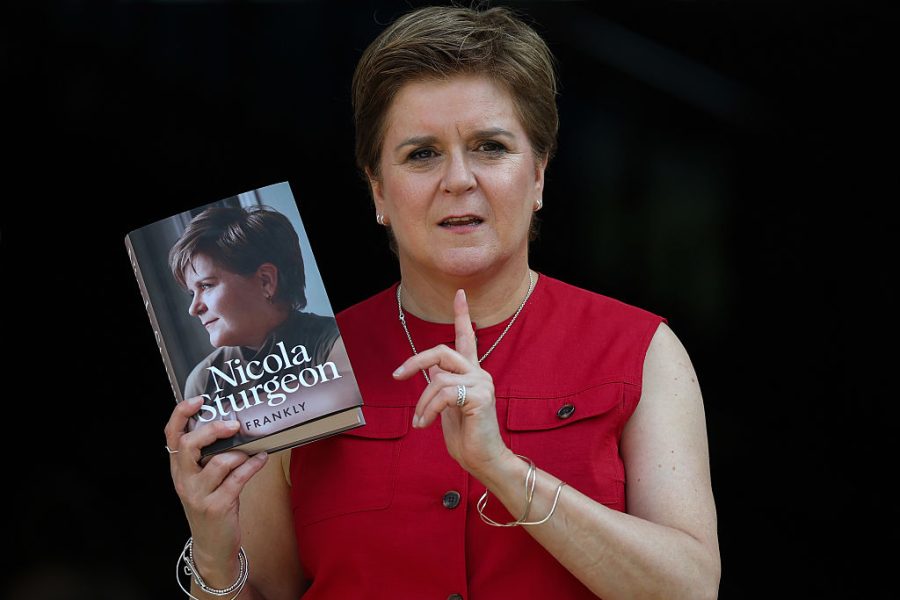

Last night, Nicola Sturgeon appeared at the Queen Elizabeth Hall to promote her autobiography Frankly. On stage she was questioned by Cathy Newman of Channel 4, who began with J.K. Rowling’s savage review of the book. On her website Rowling described Sturgeon as ‘Trumpian in her denial of reality and hard facts’.

Sturgeon fired back: ‘Thank you, J.K. Rowling. Anything that brings publicity for my book is great.’ Then a change of tone. She criticised Rowling’s decision to ‘pour vitriol on somebody’s head … I wouldn’t have the time or the inclination to do to J.K. Rowling what she does to me.’ She warned that ‘hyper-personalised’ rhetoric may have unforeseen consequences. ‘I don’t live on a yacht or behind security gates,’ she said, referring to Rowling’s opulent lifestyle. ‘It potentially makes people less safe.’ And she urged Rowling to ‘dial down the rhetoric’.

Newman asked about the convicted rapist, Adam Graham, who served time in a women’s prison after identifying as a female named ‘Isla Blair’.

‘He is a man,’ said Newman. And she invited Sturgeon to concur. ‘Isla Blair is a rapist,’ she said, avoiding the question. Pressed again, Sturgeon dodged it a second time. ‘I don’t care what Isla Blair thinks they are.’

Newman suggested that Graham ‘was able to run rings around the prison service’.

‘Not true,’ said Sturgeon. Graham received the standard treatment offered to any trans-identifying convict in the Scottish prison service. He was sent to a women’s prison ‘for assessment – and within a day or two days at most’ he was moved to a male prison. The real problem, according to Sturgeon, is that ‘the issue has been hijacked by people who want to push back on everybody’s rights’. For her, the gender-critical movement is an expansionist crusade that threatens us all. ‘Today, trans rights. Tomorrow, gay rights,’ she said, without further details. Are gay rights under attack from gender-critical activists? Many of them are lesbians who are unlikely to dismantle their own legal protections.

Sturgeon spoke of her upbringing and described herself as ‘a shy, bookish, introverted child’ who wanted ‘to do something that was a bit out of the ordinary’. But she found herself in a world where ‘a woman must be twice as good to be considered half as competent’.

Early in her career she received voice training from a famous SNP supporter, Sean Connery. He invited her to the New Club, a swish establishment on Princes Street in Edinburgh, and advised her to ‘deepen your voice on TV. It’ll give you more gravitas.’ He taught her to practise speaking with a piece of card clenched between her teeth. And it worked, she said. Her voice dropped.

She gained a reputation in public as ‘dour’ and ‘never smiling’, which she ascribed to misogyny. She said that commentators who see a happy and relaxed female politician describe her as ‘not serious enough’. ‘You can’t win,’ she sighed. Men had an easier time. She contrasted her cheerless public image with Gordon Brown’s. ‘He wasn’t known for his jolliness and I don’t think anyone characterised him in that way.’ But Brown was invariably described as a frowning misery-guts. Perhaps she read the wrong newspapers.

Sexism seems to have dogged her entire career. When she became Scotland’s First Minister she was greeted by a wealthy local businessman who always spoke formally to her predecessor, Alex Salmond. ‘Hello, First Minister,’ he used to say. No such formality with Sturgeon. He stroked her arm and said, ‘How are you doing, Nicola?’ This made her feel resentful. A shrewder stateswoman might have turned his friendliness to her advantage.

For her, the gender-critical movement is an expansionist crusade that threatens us all.

Newman asked about Alex Salmond and his alleged mistreatment of women. Sturgeon had witnessed nothing that might arouse her suspicions. ‘He didn’t behave that way with me,’ she said, although she knew he was ‘a bit of a bully’. She was even prepared to challenge him. ‘I had occasion to intervene,’ she said, ‘and to say, “enough, you’re going too far”.’ Newman suggested that she had been ‘insufficiently curious’ about Salmond’s behaviour, but Sturgeon rejected the premise of the question. As soon as a man is accused of misconduct, she said, ‘people look for the first woman to blame’.

On American politics, Newman asked how Sturgeon would deal with Donald Trump. ‘A bit more naughty-step for Trump?’ she suggested. Sturgeon refused to endorse this schoolmarmish approach and she focused on Trump’s ‘snake-oil’ rhetoric. He exploited the voters’ hardships and fears, she said, and directed their resentment towards vulnerable groups. ‘The immigrant is to blame. The gay person is to blame.’ She didn’t cite any examples of Trump ascribing America’s problems to gay people.

She said that Nigel Farage copies Trump’s tactics but he remains ‘eminently beatable’. Quitting the EU is his weak spot. ‘Many of our troubles are a direct result of Brexit. And who caused Brexit?’ she asked. Her advice to Starmer is to campaign for readmission to the EU. ‘That’s what Starmer believed and still believes.’ But his vacillations have hurt him in the polls. ‘You go into politics to stand up for what you believe in. If you don’t do that, what are you in politics for?’

She feared that Starmer had allowed Farage and Reform to ‘set the narrative and set the agenda’. And she offered a personal impression of Farage from the leaders’ debate in 2015 when his ‘fragile, brittle ego’ was on display. Backstage, she was quietly preparing alongside David Cameron, Nick Clegg and Leanne Wood of Plaid Cymru. Each of them withdrew to ‘get in the zone’ before the broadcast began. Behind her, she became aware of Farage who showed no sign of nerves or anxiety. ‘He was talking about how many glasses of beer he’d had in the green room.’ That was the end of her anecdote. But it suggested confidence rather than a ‘fragile, brittle ego’.

She is satisfied that her dream of Scottish independence will materialise. ‘I think it will happen,’ she said, although perhaps not for 20 years or more. She suggested that the British-Irish Council could be expanded and given powers to govern the British Isles. Four member states would make the decisions: ‘England, an independent Scotland, a more autonomous Wales and a united Ireland perhaps.’

To finish, Newman asked which book she turns to for inspiration. In all sincerity, she replied: ‘Charles Moore’s biography of Margaret Thatcher.’

Comments